In this weeks special report / long-read article Hasret Cetinkaya writes about the Repeal the 8th campaign in Ireland, seeking to amend the Irish constitution in order to facilitate the legislation for abortion. Hasret argues that central to these campaigns are deeper questions of patriarchy, kinship and anti-colonial struggle. What is at stake, she argues, is a matter of how we value the lives of others.

On Friday the 25thof May 2018, Ireland goes to the polls in a referendum to repeal the 8th amendment to the Irish constitution, and at stake is a constitutional change, removing article 40.3.3, which asserts that the life of the unborn is equal to the life of the mother. What is increasingly apparent, however, is the extent to which this referendum has been fought out in a space beyond that of constitutional change, and in actuality is a rich symbolic expression of the curse uttered against women throughout Irish – as well as world – history in the name of the “father” – the pater (patriarchy) premised upon a central logic of kinship and power.

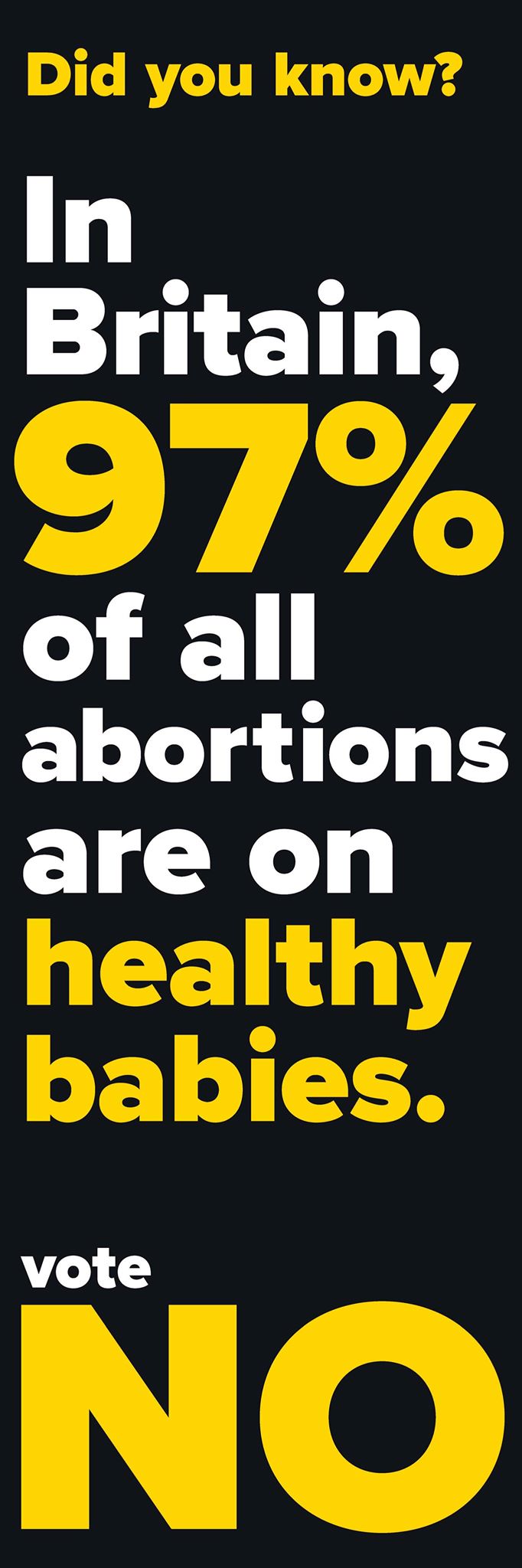

Ireland, as a postcolonial state, has utilised the body of the women to create a unique Irish identity, which is respectable, pure and radically different from those of their former British colonizers. Anti-colonial struggle is a very present element in the debate on the 8th amendment, and captured clearly through the great number of NO posters referring to 97 % of abortions being carried out in England being on healthy babies. The body of women has once again become a symbol of a newly established motherland, which is in protection of the father state to ensure the reproduction of Irish babies indicating the barely concealed ethno-nationalism seen in the debates thus far. Women are thus represented as being incapable of protecting babies, which has the consequence that the patriarchy, ironically, becomes both a protector and a violator at one and the same time.

It is thus possible that a parallel between the father state and the sperm cells can be drawn. Just like the father state is created by conquest or through battle, by one solider planting the flag of victory, and all the soldiers building together with their bodies a fence around this newly colonized territory, so too is the body of the women colonized. Thousands of sperm cells also vie for a single egg cell, and once conception has taken place, the flag planted, the body now belongs to the pater familia. The female body is both the site of plantation and reproduction whilst simultaneously constituting the borders of what constitutes Irish-ness, and because it does the latter, the decision of reproduction can never truly be upon “the thing” that brings children into-being. The soldier can thus enter this female body/land, but this female land can never enter another land/body, not to talk about entering a soldier or the emperor.

Biological qua cultural reproduction is crucial for any culture which seeks the “authority of the father” to be sustained. This understanding of womanhood premised upon the female body as prior to culture, however, fails to acknowledge how the female body is a doing, and never outside of cultural constructions. Repealing the 8th thus challenges such understandings and their force and power, since power is implicit in claims about what is considered respectable, cultural and natural.

The colours of the flag of the 25th supposedly carries death. Whether you vote no or yes, you will kill – either the mother or the foetus; the foetus before birth, before life begins, and the women you curse, once again, to ‘a life in living death’ (Butler, 2000).The vote, in reality, is a vote of who matters most, who counts as a more sacred human in this hierarchal organisation of lives. So far this year, not least with the Belfast rape trial, we have witnessed that the life of women has been de-valued, placed at the lowest end of the hierarchy, and as an object and vessel it can enable the production of subjects, but the female body itself, however, cannot be grieved. Women’s lives, once again, have no place next to the life found within the ‘legitimate community’, and yet by being outside this legitimacy the maternal bodies are already inside of it as its very condition of reproducibility. There is a multiplicity and plurality of women’s voices and experiences, and hence no single solution can be sought – only a space which allows for choice can meet all womens demands and needs. Yet, the discussion so far has not been focused politically on women’s decision-making but instead has become a debate between two moral systems, in which one condemns the other, and this has had the consequence of furthering the violence inflicted upon women’s bodies in the name of ethics – “so-called” Catholic ethics, arguably – by the no campaign.

The no-campaign’s discourse regarding women has shown their insignificant importance, constituting only a piece of land upon which to build whilst also functioning as the fences of this land. Hence, they have to be fertile and even if “God’s plan doesn’t work” and getting children is a complicated matter, mankind has found a way to ensure that the fence is even, coherent and without any cracks all the way around. It is the lack of children, the lack of sovereignty in this terrain, that is experienced as the real threat to the patriarchal ordering of life. An ordering carried out by both women and men alike.

Repealing the 8th would thus constitute a rethinking of how we approach kinship, a reconfiguration of the family, which no longer guarantees the position of “the father” and his flag. The Irish identity built upon a specific societal understanding is thus being rethought, and arguably it is in risk of no longer being premised upon the protection of the father state, but rather the will and choice of the individual body. As in any process of redefinition of norms, the end result cannot be known, but something new will emerge, and whilst that might bring with it new anxieties, such a task of redefining who the Irish are as a nation must be embraced.

In Ireland, women arguably have all the thinkable and desirable liberal freedoms, and yet large parts of the Irish society and Ireland’s recent history indicates an understanding of the ideal women’s body as “pure”. The sexed female body is just as the land that needs to be kept clean of weed and moss to ensure that anything harvested will not be poisonous for the humankind fed by it. I am referring to the Magdalene Laundries and Mother and Baby Homes – the known unknowns in Irish history, where deviant and unmarried women were hidden away when they could bring shame upon their kin. The figure of the woman is thus always already cursed and to this present day obliged to conform to such norms of purity and piety to avoid bringing shame to the door of the pater. The female body in Ireland, previously, had to be hidden away, and arguably still does albeit in a different form, when conventional norms of when pregnancy can take place has been breached. The question is to what extent the lack of access to abortion is a form of punishment uttered by the “father” for a “self-inflicted criminality”? A punishment, which functions as form of normative violence, that shapes the limits of what a respectable life is.

Women’s present sense of bodily integrity, which challenges what no patriarchy could have foreseen, is now being challenged at its limits with this referendum. In many ways the referendum can be seen as another loss for the forces of patriarchy after the #MeToo and #Ibelieveher (a tag trending on social media following a Belfast rape trial which acquitted all four defendants) movements successes. Now, as a result of such developments, the patriarchy is even louder, because giving women more power and control is a threat to the current structures of distributed power. That said, it would be an extreme generalisation to see the referendum as the curse of gender and the gender struggle, and yet it is also through this lens we come to see how the patriarchy functions by claiming a certain hierarchy and superiority in which women’s freedom so far has met its limits, since choice is made on her behalf. In this regard it is important to mention that a woman choosing to abort a foetus, never does so because of her lack of love towards what would become a baby, but rather because of difficult circumstances. As Mary Lou McDonald TD and Uachtarán Shinn Féin said on RTÉ the other evening, ‘we say very often that hard cases make bad laws; but in these circumstances what we are witnessing is bad law creating very difficult and hard cases’.

The superiority of the patriarch supposedly comes with hiding away the bodies of women. For how much are women actually worth if they decide not to be a bridge between the divine and mankind? Such a discourse’s underlying message is that woman must be chaste and adhere to standards that benefits the notion of the family – despite women’s newly owned bodily integrity – and if she fails with her promiscuous behaviour and gets pregnant she has to live with her female body under all circumstances, the female body has been condemned to ‘a life in living death’. Yet, the buried and lesser human is now returning with the support of many of those considered “superior” humans, following years of campaigning and the latest staging of a claim.

Hasret Cetinkaya is a doctoral candidate at the Irish Centre for Human Rights at the National University of Ireland – Galway. Her research interests are postcolonial and feminist theory, gender, kinship and the sociology of human rights.