Conspiracy theories and post-truth politics have figured prominently in the popular consciousness throughout 2020; growing steadily alongside public health responses to the Covid-19 pandemic. These conspiracies have been broadly dismissed in both leftist and liberal circles, as many of them are tied to forms of aspirational fascism. This is particularly apparent when it comes to QAnon, which tends to function as a Master-Signifier around which many conspiracy theories have started to stabilise. Growing out of a cryptic post by an anonymous account on 4chan, the QAnon movement asserts that the world is run by a cabal of elite satanic paedophiles. They argue that Donald Trump is leading the fight against this conspiracy and that he will soon initiate ‘the storm’, whereby thousands of celebrities and politicians will be summarily executed—although it is yet unclear how he will do so after losing his bid for re-election. Building on Kuraishi’s observation that post-truth discourse “is reflective of a socially constructed narrative which is aimed at offering a specific version of reality”, we can think of such conspiracy theories and post-truth politics as productive of alternative realities.

The impulse to dismiss QAnon as irrational is initially very tempting, yet I want to take a slightly more generous reading of them by drawing attention to the age-old tendency of ridiculing popular movements by painting them as conspiracy theorists. Support for QAnon or any of its sub-conspiracies tends to be written off as being divorced from reality at best, or, at worst, symptoms of a fascist mindset. Academic discourse on conspiracy theories, in turn, is often not much more charitable than popular discourse. The central question of much of the literature on conspiracy theories—why more or less normal people would embrace paranoid and conspiratorial fantasy—draws heavily on Richard Hofstadter’s 1964 essay the Paranoid Style in American Politics. Hofstadter’s own answer to this question focused mostly on individual psychology rather than structural factors and, as Hellinger pointed out, this approach of treating conspiracy thinking as little more than a psychological illness still dominates conspiracy theory research.

The Paranoid Style, as well as Hofstadter’s the Age of Reform: from Bryan to FDR, were essentially character assassinations of the American populist movement of the 1890s. The treatment of the populists as conspiracy theorists, by Hofstadter as well as many others, presents a clear example of how broadly inclusive emancipatory movements are unfairly dismissed as irrational and incompetent. As Frank describes in his history of anti-populism, the situation for small-scale farmers in the United States became increasingly dire in the late nineteenth century, for the most part due to rolling economic crises and bad harvests. Even though politicians from both parties had started to respond to their grievances—particularly in western states where these small-scale farmers represented a huge proportion of the population—they never delivered. As soon as they got to the state capitals, or even to Washington, business interests had a habit of getting in their way.

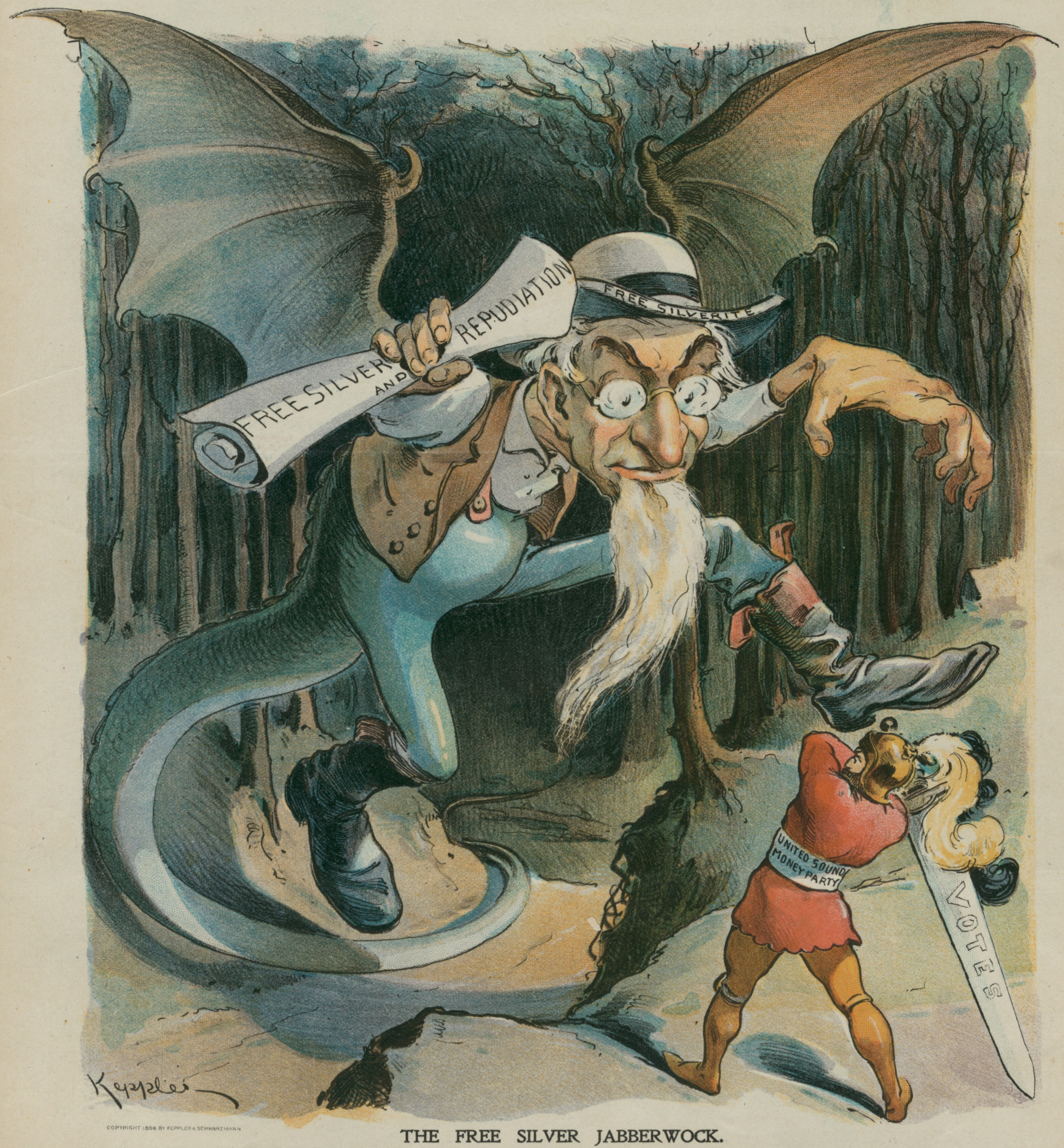

By the early 1890s, the situation had reached a crisis point, and the farmers launched the People’s Party in 1892—self-consciously calling themselves Populists. They ran on a platform of collective bargaining, federal regulation of railroad rates, and the abolition of the gold standard. Their opposition to the gold standard is particularly important. By the late eighteen-hundreds, the American gold-rush was mostly over, and because the dollar was tied directly to the country’s gold reserves, the amount of currency in circulation was fixed. Because the population as well as the means of production kept growing, however, there was constant deflation. Many farmers had needed to borrow money to survive several bad harvests, but because of this deflation they would earn less every year while their debt stayed the same, so a lot of them had to choose between eviction or debt peonage. In Laclau’s terms, the empty signifier that came to stand for the solution to all of the farmer’s problems was “free silver”, as they sought to replace the gold standard with the much more widely available silver. Free silver came to signify an end to debt, and end to exploitation, and to many, even an end to bad harvests.

Beyond the vitriol launched at the populists by the political establishment which has deeply influenced the anti-populist playbook used today—that they were supposedly anti-intellectual and anti-democratic—they were painted as wild-eyed conspiracy theorists. As Frank recounts, the farmers’ concerns were largely disregarded by the ‘sensible’ voices in the media at the time. Some people may have been going through tough times, but that is merely the way the world works. The real problem, as it was perceived, was populist demagogues convincing the farmers that bankers and financiers behind their misery. Blaming the elites for their situation was seen, in and of itself, a paranoid fantasy. As Stavrakakis shows, Hofstadter then built on this even further by arguing that the populists’ campaign for silver and their hatred for the bankers was actually a sign of their profound anti-Semitism.

With hindsight, though, all these points turned out to be less than true, and Hofstadter had to walk back his claim that the populists were xenophobes and anti-Semites. Stavrakakis quotes Hofstadter’s admission to a former student that “certain kinds of nativism and anti-Semitism were in fact fairly common in American society in the 1890s, in urban as well as in rural areas, and it was a serious deficiency of my book that I did not give any attention to this, and thus inferentially suggested that the Populists were the sole or primary carriers of this kind of feeling”. Blaming a cabal of bankers for their situation was no paranoid delusion either. As DeCanio has shown, throughout the eighteen-hundreds, bankers did in fact pay large bribes to politicians to influence monetary policy. Today this would probably be considered a ‘campaign donation’, but this was during a time when corruption was still technically illegal in American politics.

The problem with denouncing conspiracies outright is that some of them are right, and many more of them are half-right. To the educated and prosperous Americans of the 1890s, it seemed wildly irrational that people would be against the banks, the gold standard, and laissez-faire liberalism. With hindsight, however, it turned out this scholarly consensus did not have any clearer a view of ‘Reality’ than did the populists. QAnon’s theories, similarly, are at least to some extent based on ‘Reality’. More importantly, these are often truths that the dominant discourse refuses to recognise. The assertion that the world is run by a cabal of Satanist paedophiles is probably questionable at best, but it’s more difficult to deny that there are a lot of wealthy and powerful people who are credibly accused of paedophilia, sexual assault, and rape, yet very conveniently manage to evade justice. Prince Andrew, Donald Trump, Joe Biden; the fact that all of these people manage to remain in positions of power does point out that there is one set of laws for the wealthy and the powerful, and another for everybody else.

QAnon also takes issue with the so-called deep state, the entrenched interests in the American political system which supposedly seeks to undermine American democracy. Again, this view of the deep state is probably an overstatement, but it is well-documented that there are factions within the intelligence and business communities who—sometimes illegally—attempt to guide policy in their preferred direction.

A better way of thinking about conspiracy theories, then, is as heterodox explanations for social problems. Bruno Latour pointed out that conspiracy theories, in this sense, are similar to critical theory; they share a logic in seeking to undermine our received and preconceived notions of our shared ‘Reality.’ In other words, they challenge what Foucault calls the Regime of Truth. The regime of truth describes the way in which we make sense of the world around us as a collaborative project. This is less about what is actually true—in the sense of a subject-independent reality that exists ‘out there’—than about what is socially agreed upon to be true and what can be said within the public sphere without sounding ridiculous. The case of the People’s Party serves as a reminder that the term ‘conspiracy theory’ is wielded pejoratively to call any theory which falls outside of the dominant regime of truth insane. A brief look at Karl Popper’s assessment of Marxist historical dialectics as the ‘conspiracy theory of history’, moreover, highlights that this strategy of delegitimising critique was by no means limited to the populists.

As an example of the similarities between critical theory and conspiracy theories, take some of the theories that came out of the QAnon community in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Because QAnon crowd-sources its narratives on social media, the community’s stance on the pandemic was incredibly fluid and often contradictory. At various points throughout the last nine months, it has been claimed that the pandemic and its death toll were pure fiction; that the pandemic was a plan carried out by the Bill and Melinda Gates foundation; that the pandemic was a deep-state plot to undermine Trump; and that the pandemic was a hoax perpetrated by Trump himself to provide cover for the arrest of members of the deep-state cabal. On the face of it, some of these theories are not too dissimilar to the claims Giorgio Agamben makes in the Invention of an Epidemic. Agamben argued that “the frenetic, irrational and entirely unfounded emergency measures adopted against the alleged epidemic of coronavirus” are symptomatic of a public health situation blown completely out of proportion by the state in a biopolitical effort to curb individual liberties.

In both cases, we have a reading of the events happening in the world around us that challenges the dominant narrative. That is not to say that there is no difference at all between Agamben and QAnon. Whereas Agamben’s worry that the state is likely to use any crisis to establish a state of exception fits quite clearly with observations of state behaviour over the last century, some of the claims made by the QAnon community have a more questionable relationship with any observations we can make about the world.

Fundamentally, both conspiracy theories and critical theories take a set of observable data-points and weave them into a narrative which de-familiarises ‘Reality’. Central to this process of undermining the regime of truth is an attempt to challenge the givenness of history—claiming, essentially, that there is a hidden cause behind these phenomena. Let us take the astounding levels of inequality in much of the world today as an example. The dominant neoliberal narrative explains that this inequality—whether between the global north and the global south, or between rich and poor within individual states—is completely natural. Nobody caused it to be that way (definitely not the invisible hand of the market). It just happens. Critical/conspiracy theory, however, would claim that this situation is anything but natural. The ‘mainstream’ narrative, that inequality is natural, hides the fact that levels of inequality were lower for much of the twentieth century, and that the choice to adopt the deregulatory neoliberal policies which increased inequality was not historically determined. Claiming that the insecurity and precarity so many people face are just unavoidable facts of life rather than the result of consciously made political decisions sounds as disingenuous now as it did in 1896.

If reality is for a large part socially constructed, then it is a reasonable question to ask why it was constructed in this way rather than another. The dismissal of conspiracy theorists who seek behind every event a perpetrator, then, often function as implicit denials of the social construction of reality as well as the suggestion that it could be otherwise. Where Agamben, and left-leaning theories in general, tend to focus more on structural factors as creative of our world (in this case, sovereign power), QAnon takes a more agent-centric approach. Rather than patriarchal, capitalist, imperialist, colonial, or other dominating structures being the cause of all our problems, it is the cabal of specific individuals who have secretly taken charge—and god-emperor Trump is here to offer salvation.

While I have largely treated the similarities between conspiracy theories and critical theory as an opportunity to rehabilitate conspiracy theories, it is at this point that I do agree with the popular discourse that QAnon is incredibly problematic. The complete avoidance of structural factors as central to critique is by no means innocent. In fact, this logic follows very closely Benjamin’s depiction of Fascism as an aestheticization of politics which leaves the economic base intact, or in fact accelerates its logic. My issue with conspiracy theories such as QAnon, then, is not that they are somehow detached from ‘Truth’ or ‘Reality’—it’s that their critique is naively aesthetic. Nonetheless, because the term ‘conspiracy theory’ operates as a thought-terminating cliché, there are many legitimate critiques which are equally discarded offhand, and this plasters over the shortcomings of the orthodox discourse.

The belated vindication of many conspiracy theories reminds us that the regime of truth is not always on the side of ‘Truth’, meaning it must constantly be questioned. Going a step further, the currently dominant regime of truth deserves to be undermined. We live in a ‘Reality’ where we can accept that climate change is an existential threat while resolutely refusing to do anything to address it, where the UK and the USA are the staunchest of defenders of human rights and democracy across the globe, and where inequality and poverty would not be an issue if only we could just stop drinking lattes and eating avocado toast. It is not the conspiracy/critical theorists we should be polemicising against—those exposing the flaws in ‘our’ regime of truth are not to blame for the existence of these flaws. Rather than ridiculing those seeking explanations for their alienation, a better question to ask is why so many people are alienated in the first place.

Sebastiaan Bierema is a PhD researcher in the School of Political Science and Sociology at the National University of Ireland – Galway. Sebastiaan tweets at @seb_bierema