In this weekend’s long read, Steven Gormley examines the issue of free speech as it applies to speech acts which are offensive to religious minorities. Taking the recent comments by Boris Johnson as exemplary, Gormley argues that ‘in modern conditions of instantaneous communication and violence directed at certain minorities, one does not have to be outside the other’s door for one’s speech acts to have harmful effects.’

‘These days you get arrested and thrown in jail if you say you’re English, don’t you’, says the proverbial taxi driver in a Stewart Lee comedy routine. The routine consists of an increasingly bewildered Lee checking that the taxi driver actually means what he says. After a two-minute exchange, in which the taxi driver’s statement is repeated (with slight variations) 18 times, the taxi driver confirms that he is not, in fact, saying that people will be put in jail for saying they are English. The taxi driver continues: ‘But, if on an official form where it says nationality you cross out “British” and you write in “White English” they will send that form back’. As Lee observes: ‘Now, that’s not strictly…the same as being arrested, is it’.

While Lee’s taxi driver is a comedic prop, he’s all too real. In the wake of Boris Johnson having to make journalists cups of tea for saying that Muslim women wearing the niqab or burqa look like letterboxes and bank robbers, I unwisely got involved in a public exchange. My interlocutor asserted that ‘you can’t say “blackboard” now’ and that:

‘You can be in a restaurant discussing current issues, have a few drinks, things are said, some of them outrageous, just for the fun of it, but as long as this conversation isn’t taped you’re safe. But if taped, suddenly you are judged, with people calling for you to be arrested or killed. We don’t have free speech any more’.

Had the exchange continued, I might have replied: ‘Now, a minister of government, with designs on becoming the next prime minister, publishing those comments in a national newspaper, is not, strictly speaking, the same as a hypothetical scenario involving friends having their private conversation in a restaurant secretly recorded and then being threatened with death’. Despite the absurdity of the examples offered, both Lee’s taxi driver and my interlocutor express a sentiment that many share, namely, that ‘we don’t have free speech anymore’. Do those who assert this actually mean what they say?

Johnson exercised such freedom in publishing those remarks. And while serving tea to journalists, he was not rugby tackled to the floor by waiting police. Police have confirmed that they received no criminal complaints about Johnson’s article and that no criminal offence was committed. Katie Hopkins exercised such freedom when she published an article in a national newspaper describing migrants as ‘cockroaches’ and conjuring up ‘pictures of coffins’ and ‘bodies floating in water’. Hopkins was convicted of no crime and complaints to the press regulator were not upheld. We are not, it would seem, inhabitants of Airstrip One, just yet. While there are calls for the Conservative party to open an investigation to ascertain if Johnson’s remarks breached its own code of conduct, this is hardly the stuff of the Inquisition. Johnson is no Giordano Bruno.

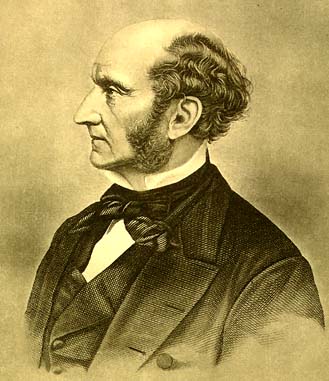

But perhaps those mourning the death of free speech are not pointing to legal restrictions on one’s right to express certain opinions. Invoking JS Mill’s distinction, perhaps it’s ‘the social tyranny of prevailing opinion and feeling’ rather than ‘the tyranny of the magistrate’ that has our friends in the restaurant worried about making outrageous jokes. And indeed, this is how the debate on free speech is often framed: my freedom to make “outrageous” jokes vs. your feeling of offence. Seeking to counter this social tyranny, Rowan Atkinson, in his defence of Johnson, notes blithely, ‘All jokes about religion cause offence, so it’s pointless apologising for them’. But this is to skew the debate in important ways.

Firstly, by framing it this way, one party to the dispute is positioned as being against free speech. This is a distortion. The issue, rather, is about balancing two key features of liberal democracy: the freedom to express opinions and the obligation to avoid harming others. So while Atkinson’s 2012 argument opposing legislation against offending others seems all very sensible, it does not touch the problem of harm. Well, Atkinson does highlight the harm caused to those arrested under wrong and ludicrous interpretations of the Public Order Act, and rightly so. But no consideration is given to the harm speech acts may cause to those in a vulnerable social position. Again, in this speech Atkinson rightly notes how legal restrictions on speech can become tools to oppress minorities. But, again, there’s no mention of how minorities may be harmed by various speech acts. In current conditions, I imagine that a pensioner walking down the street wearing a niqab or burqa is more concerned about not being attacked than being offended.

This leads to my second point. Jokes, like any speech act, have effects in the world. We do things with words, as John Austin put it. By insisting that the only judgement we need to make is whether a joke is any good, Atkinson simply ignores this. It’s as if laughter magically dissolves harm. Jokes, even good ones, can cause harm depending on the context. And in current conditions, where Muslims are being increasingly targeted for abuse and assault, jokes can contribute to that climate. And that is what seems to have happened in this case.

While Johnson’s article refers to Mill’s harm principle, he does not reflect on what that principle may mean for his own speech acts. Mill is seen as the great liberal champion of free speech, but he recognises that it’s limited by potential harm to others. Mill imagines an excited mob assembled outside a corn dealer’s house and argues that one does not have the freedom to hand out placards stating that corn dealers are starving the poor. Immediately after this, Mill writes:

‘Acts, of whatever kind, which, without justifiable cause, do harm to others, may be, and in more important cases absolutely require to be, controlled by unfavorable sentiments and, when needful, by the active interference of mankind’.

There are plenty of things in the world to laugh about. It’s no great impoverishment of my world to refrain from making certain jokes where I judge conditions to be such that I may cause harm to vulnerable others. While this does not license throwing taxi drivers in jail or killing my fellow restaurant diners, it does license directing ‘unfavourable sentiments’ to those who publicly produce such speech acts and, on occasion, it may justify ‘active interference’. This will always be a matter of judgement. But in modern conditions of instantaneous communication and violence directed at certain minorities, one does not have to be outside the other’s door for one’s speech acts to have harmful effects.

Steven Gormley is a lecturer in philosophy at the University of Essex. He has published articles on the the politics of deconstruction, forgiveness, and the role of rhetoric in democratic deliberation. He is currently working on a book discussing deconstructive and deliberative accounts of doing justice to the other.