Despite the near consensus around the urgent need for action on the ecological problems we face, as well as the majority interest for greater wealth redistribution within our economies, those political forces striving for such social transformations continue to struggle in capturing the imagination of the people when it comes to elections. Beyond these more common sense issues, perhaps the problem lies in the failure of the left to provide inspiration to those for whom liberalism and its mythical narrative still promises a future of success and personal triumph. Is it within the interests of the left to explore a politics of the irrational in order to enlarge its electorate, without perverting its own project? By Ménélas Kosadinos.

Becoming a billionaire cannot be a healthy ambition

One of the determining components of political opinion is, undoubtedly, the space left open to dream, as offered by a given vision of the future. The first round of the 2017 French presidential election can be interpreted in this sense. Where Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s search for the common good program was swept away by Emmanuel Macron’s liberal project was in the latter’s ability to reach people in their desire for a better future.

When Emmanuel Macron spoke of the young people who want to become billionaires, he projected a fantasy with a capacity to throw hordes of would-be and soon-to-be exploited young people into the mouth of liberalism. Macron knows how to transcend reason, and whispers to everyone: “you could be that billionaire”.

This desire for individual success and triumph cannot be simply put down to the supposed bad nature of humans, a rhetorical move so often used to justify neoliberal rationality, for such a desire is indeed a social construct and a cultural phenomenon.

Culture at the service of a dead-end model

The form of power a state has when exercised through influence and consensus rather than constraint and coercion is called soft power: it refers to those cultural means by which the state promotes and secures their regime and ideology. But this form of cultural power is more fundamental than the mere operation of disseminating values: cultural production penetrates the desires of the consumer, creating a total adherence to capitalism.

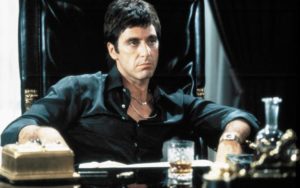

In this regard, we can invoke the soft power of every American cinematic and televisual production, since they each glorify the success of the individual – the most effective of which, being those that are most excessive. The hero, and that figure with whom we are encouraged to identify with, is sometimes that character whose values transgress those norms advocated by the official discourse; but those values nonetheless intimately connect with the content of that same discourse. From the myth of the “self-made man” to the protagonists of gangster films, the fascination with these heroes for liberalism lies in their role as selling a model, a dream, in which one fantasizes the impossible ascension to the position of billionaire. What are the gangsters of cinema if not those figures that closest represent the entrepreneurs as imagined by advocates of unfettered capitalism: people that are freed from the laws and the constraints of the state?

For if the priority for the common good, such as reflected by the ecological challenge, seems designated as such a good by the exercise of reason, the power of the fantasy of liberalism seems to nullify all rational considerations. We can ask ourselves – slightly provocatively: whom do we find most “fascinatingly attractive” between Caroline Lucas and Tony Montana? For any ecological transition to happen citizens need to accept the absolute necessity of such a transformation; but they also need to express an enthusiastic consent, without which any sense of necessary urgency for change will be lost. It is therefore an urgent imperative for the left to make progress attractive or “cool”, so that even those better-off constituents feel that urge and throw themselves into the battle. This is not a politics of spin and marketing, but a cultural politics capable of addressing an ever-wider constituency of supporters.

Building another dream for the individual and the collective

In order to bring about a cultural counteroffensive, the advocates of revolutionary projects, of social transformation, and of environmental preservation – those that one could arguably call the left – must in turn build that space for a both individual and collective dream to emerge, thus fostering a connection between those who indulge in individualistic fantasies and the revolutionary ideology of the left. This does not deny the part of the dream and aesthetic that drives the revolutionary forces, but one must note the incompatibility of that ideal with the dream of individualistic triumph. This new space for alternative fantasies could counterbalance the weight of dreams and desires created by the neoliberal hegemony. It is indeed extremely complex to make such opposing ideals connect and coincide; a complexity which is aggravated by the necessity to err away from compromise.

Within its on-going process of reimagining and reinvention, the left must learn to offer that space of irrationality and reverie, a space of emotion and fantasy without losing its radical and emancipatory content. It is an absolute prerequisite for a victory of the progressive forces to build a collective dream strong enough to erase individualistic ambitions and draw new voters to the project of the left.

This article was translated into English from the website of our French partner LVSL by Phileas Cherkaoui.