In this fascinating article, Steven Parfitt draws lessons from the rise and fall of the Knights of Labor —the first left populist movement and national industrial union in the history of the United States. For over a decade, during the 1880s, the Knights heralded the hopes of American commoners. Their agile —and somewhat ambiguous— rhetoric succeeded in building a strong coalition of farmers and workers which amounted to 700,000 members in 1884. Soon however, the Knights were supplanted by the American Federation of Labor whose militancy proved better suited to the radicalisation of class conflict in the 1890s. The story of the Knights, according to Parfitt, reminds us that left populist rhetoric is vain without strong union solidarity.

When those of us on the other side of the Atlantic want to look for the origins of populism as a political practice they often turn to the People’s Party, formed in the United States in 1891. They recall the spirit if not the content of William Jennings Bryan’s famous “cross of gold speech” and if few of us now look for salvation in the free coining of silver, we still remember his belief in the opposition of a virtuous people to the moneyed interests of the country. Parties on left and right continue to adapt Bryan’s basic premise to their own situations today. Whether they do so to exclude foreigners from their blood and soil versions of nationalism, as they do on the right, or to build the widest popular coalition against the “one percent,” as on the left, the traces of the old Bryanite rhetoric have come back. Even the use of populism as a kind of centrist swear word to write off all opponents as untrustworthy demagogues has its origins in debates about the American populist legacy. Richard Hofstadter’s analysis of a “paranoid style” in American politics, lumping together Bryan with senator Joseph McCarthy, was an early example of the p-word in action.

The People’s Party, in other words, is back as a precursor and point of comparison to today’s populist movements. And it is only one part of a longer history of American parties, movements and organisations that would fall within modern definitions of populism. Some were on the right. The Know-Nothings of the 1850s constructed an image of the people in which Catholics were very much excluded; and the anti-Chinese movements of the 1870s and 1880s restricted the boundaries of “the people” still further to exclude immigrants from Asia. Other populists, broadly defined, came more often from the left. American history is replete with agitations against the Money Power, the Slave Power, and the forces of accumulated wealth. They were by no means immune from the exclusionary tendencies of their counterparts on the right: the People’s Party itself was hardly free from antisemetic prejudice; and most movements based on the common or working people practised some form of exclusion against black Americans, foreigners or women. If we are searching here for Chantal Mouffe’s ideal left populist coalition – a coalition of all the different oppressed groups that we can gather under the heading of “the people” – we are bound to be disappointed.

But there are still things we can learn from past movements: from their failings and their strengths. They make us consider whether populism, in practice or rhetoric, is the best or even a good strategy for the left to adopt as we confront the many crises now unfurling across the world. And the sharpest of these examples, the one that points to the potential of a populist strategy as well as to its many limitations, is the Knights of Labor. The Knights began in 1869 and were, by the 1880s, the first truly national working class movement in American history. They reached at least 700000 members in 1886, and although they were eventually crushed by internal divisions and the combined forces of business and the state, they played an important role in the early days of the People’s Party. Many Populists were also Knights, and the Knights officially put their support behind the people’s party in 1892, when they still had around 100,000 members.

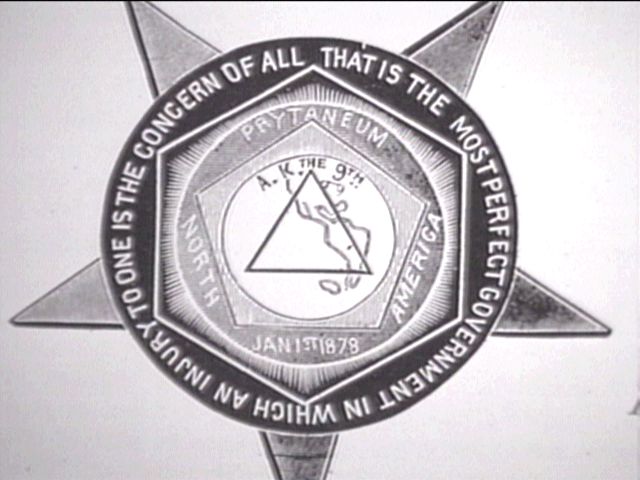

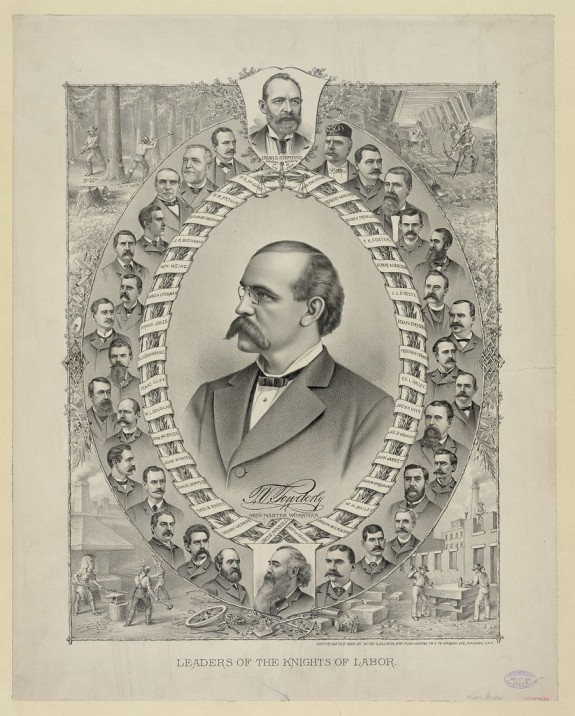

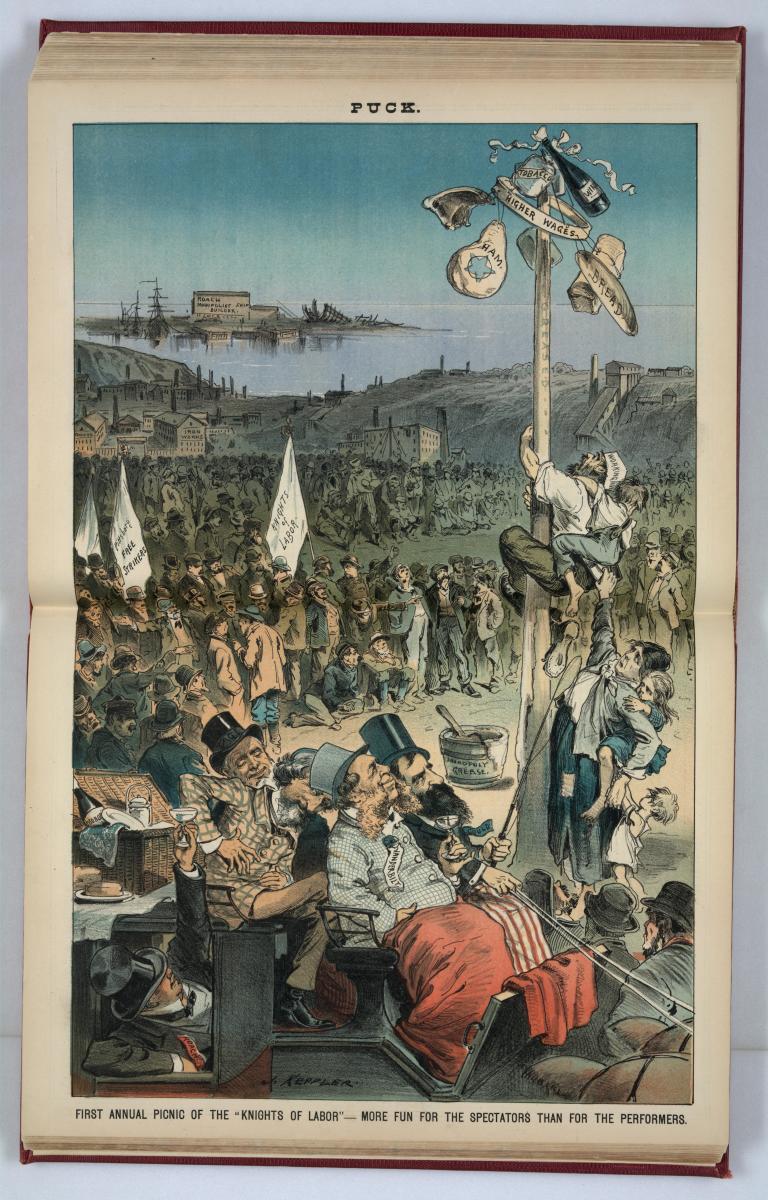

Nor were they another dry trade union federation, like the American Federation of Labor which ultimately supplanted them. The Knights had the ritual, strange titles and secret signs of a Masonic order. Their leader, Terence Powderly, was originally styled as the Grand Master Workman – later on, they dropped the “Grand” in favour of the more democratic “General.” They formed cooperatives, reading rooms and temperance societies; held poetry nights and political meetings; and protected workers’ rights through bargaining, boycotting and striking. Most importantly for this discussion, they didn’t think of their mission in narrow economistic terms. Rather, they drew a broad distinction between the producers and the parasites. They were, in other words, the purveyors of a form of populism. Their history, like that of other movements we might now think of as populist, can tell us a lot about the limitations of thinking in populist terms today.

The Knights of Labor as Populists

The Knights of Labor drew a division in American society that was at once stark and vague. The very first sentences of their Declaration of Principles made clear what they thought the problem was and what they needed to do to fix it. “The alarming development and aggressiveness of great capitalists and corporations, unless checked, will inevitably lead to the pauperization and hopeless degradation of the toiling masses,” they insisted. “It is imperative, if we desire to enjoy the full blessings of life, that a check be placed upon unjust accumulation, and the power for evil of aggregated wealth.” Update the language, and it comes straight out of a Bernie Sanders stump speech in 2016.

Their membership criteria was similarly broad. Women and African Americans were invited to join the movement, with each group accounting for around 10% of total membership at the group’s height. Aside from financiers and speculators, Knights drew their line in moral terms: no vendors of alcohol (an artefact of their leaders’ aversion to booze), gamblers, or lawyers were accepted. Their call to follow the Biblical injunction, “in the sweat of thy labour shalt thou eat bread,” divided American society into those who performed productive labour and those who didn’t, with the first category including small businessmen, farmers and even some small manufacturers as well as those who worked for a wage. This, indeed, was not a Marxist conception of the working class. It was much closer to the kind of populist coalition advocated by Podemos, Syriza, or indeed by Sanders in the US or (to a lesser extent) Corbyn in the UK. The many, or the 99%, are all those who work, including those working for themselves. The few, or the 1%, are those who live off the labour of others, and whose lives fall outside certain moral categories.

The Knights were by no means immune from the prevarications and doubts of many “left-populists” today on who they might include or exclude from the people. The Knights never quite developed a coherent plan for what to do about the foreigner. On the one hand, they spoke with one largely racist voice (with a few honourable exceptions) about the evils of Chinese immigration and often extended their vitriol to those from southern and eastern Europe. On the other, they limited their lobbying of government to a “contract-labor” law, which banned businesses from employing foreign workers, sight unseen and often under false pretences, to break strikes or weaken a closed union shop. In practice, if not in rhetoric, they sought no other barriers against mass immigration. This, at a time when the number of immigrants to the United States was proportionately far greater than the number of refugees and so-called “economic migrants” from Africa and Asia today.

Their stance on nationalism was equally contradictory. Terence Powderly loved to write effusively about the joys of American citizenship and the virtues of the American Republic, so much so that his internal enemies used to disparage his effusions as “Yankee-doodleism” and “spread-eagleism.” Powderly, himself the son of Irish immigrants, wanted Knights to make the Fourth of July a sort-of labour holiday and present their movement as patriotic rather than some foreign-backed conspiracy of Catholics, communists and other undesirables. Despite his best efforts, the powerful nativists of the 1880s never forgave Powderly for his Catholic connections or his supposed links to anarchists and other reds; and even the Catholic Church initially banned believers from joining the Knights.

Yet for all his flag waving the Knights became an international movement. They preached the virtues of Universal Brotherhood – a universality not bounded by national borders. They organised branches in Belgium, the UK, Ireland, France, Italy, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa as well as in Canada and the USA. Knights hoped that the growth of these overseas branches would raise the standard of living in other places, so that people there would not need to cram aboard crowded passenger steamers in search of higher wages in the New World. Whatever criticisms we might make of that idea, it is far more expansive – far more concerned with conditions in the rest of the world – and with the relationship between immigration and an unequal global distribution of wages – than today’s populists of the left usually put forward.

The Knights of Labor in Politics

The Knights’ political ventures point to other failings in the populist project. They began and ended as a labour organisation, which represented industrial and other workers (including housewives) in the factory or shop or home. They carried out the functions of a trade union. Despite many of their leaders’ antipathy towards strikes – many of whom had seen the consequences of failed strikes in the depression of the 1870s and as a result preferred at almost any costs to substitute negotiations for a walkout – the Knights enrolled hundreds of thousands of members in the wake of mass strikes on the railroads. In many communities the local assembly (branch) of the Knights of Labor also operated co-operatives, supplied reading rooms, supported women’s suffrage or temperance organisations, and served in general as the local hub of working-class life.

The permanence of these networks of clubs, societies and unions should not be overemphasised. American workers were highly mobile, foreign-born or not, and many local assemblies appeared and disappeared with barely time for a meeting and a few resolutions in between. Yet in the brief time between 1885 and 1887 when the Knights became a national movement with over 700,000 members, these local assemblies gave a certain cohesion to working-class life – and in rural areas, to some farmers and agricultural workers as well. That cohesion made a labour politics possible. While Terence Powderly, General Master Workman (President) of the Knights, and many of their other national leaders told their members to keep their movement outwith Politics – and while many of them nonetheless ran for office or, like Powderly did in Scranton, Pennsylvania, held office as mayor – scores of local assemblies put up their own candidates for election. As Leon Fink has described in Workingmen’s Democracy, some assemblies chose to take over their local Democratic or Republican parties. In many other cases, they created local labour parties to fight elections at local, state and federal levels.

Journalists today like to talk about political earthquakes and this was one of them. Between 1885 and 1887 Americans elected dozens of mayors, state assemblymen and even a few US congressmen on labour tickets. The radical economist Henry George, running on the United Labor ticket, nearly defeated the Democratic candidate for the mayoralty of New York City in 1886, Abram Hewitt, and pushed the future Republican president Theodore Roosevelt into third place. It briefly seemed as if the two major parties would soon face a powerful labour challenge, perhaps even a national Labor Party. Foreign observers such as Eleanor Marx talked about creating a British Labour Party that would follow the American example – and not the other way around. This was not a populist challenge per se, unless we go so far as to describe as populist every movement which calls for radical change and sees a distinction between the elites and the rest, regardless of its specific content. It was, instead, a forerunner to the American Labor Party that never was, based on large parts of the Knights of Labor.

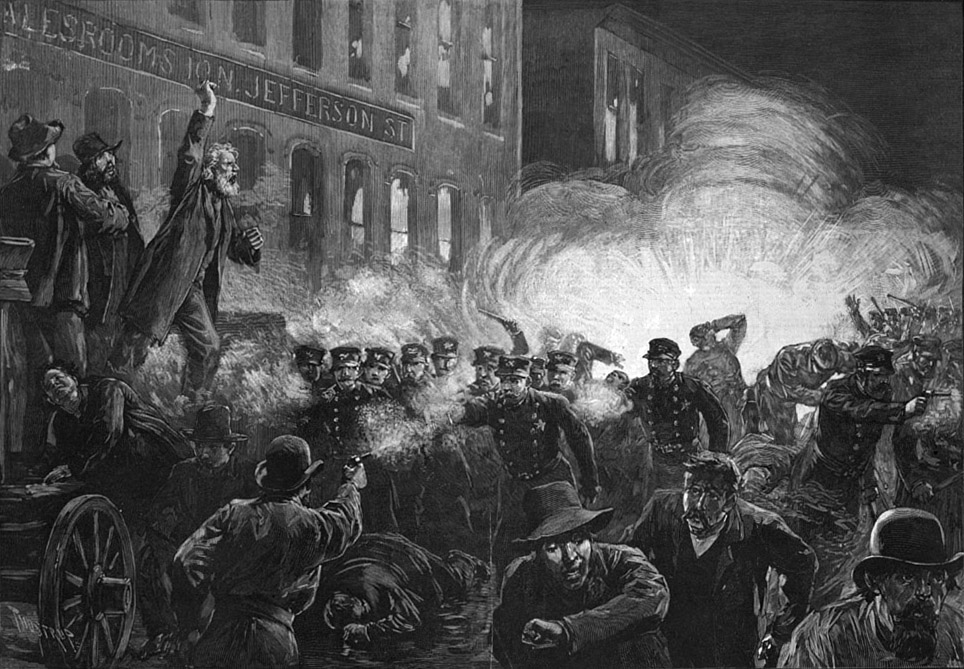

The political earthquake of 1886 was not followed by another. In that year, the Haymarket Affair – when anarchists were accused of throwing bombs at police during a protest at Chicago’s Haymarket Square in May – became the excuse for America’s first Red Scare. The Knights were driven out of the mass industries, sometimes bloodily, by employers and their armies of private detectives. The Knights of Labor could not withstand this assault from Corporate America. They were further weakened by the revival of rival trade unions under the banner of the American Federation of Labor, whose leader, Samuel Gompers, was not about to encourage a new labour politics independent of the two major parties.

When the Knights allied with the new People’s Party in 1891 they were a shadow of their 1886 selves. Most of their 100,000 or so members were now in rural areas, the precise demographic which briefly sustained the Populists for the rest of the nineteenth century. And while William Jennings Bryan and other populists tried to appeal to industrial workers as well as farmers, they never won the support of a large body of trade unionists or dug many roots in working-class life as the Knights had once done. They had a social base for their movement in the countryside, rooted in the Farmers’ Alliance and the Grangers, but one that remained unstable. They also had Bryan’s soaring rhetoric, which was, with relative ease, conscripted in the service of the Democratic Party in 1896, when he became its candidate for president. It turns out that it can be rather easy for politicians of the establishment to plagiarise a populist language without addressing the anger that led to it. Words alone do not a political movement make.

The Limits of Rhetoric

Those conclusions leave us with a more profound problem than any debate about the right construction of political language. They leave us, in fact, with the need for the reconstruction of a social fabric rent (in the UK at least) by years of government cuts, deindustrialisation and union decline. To put it a different way: we need to revive the unions if any political force on the left is to successfully challenge for political power.

The Knights of Labor built and expanded and inherited a vast network of associations – unions, clubs, coops, community services and societies- that made it possible for them to contend for political power. The same associational landscape sustained the social democratic, anarchist and communist movements of the industrial countries in the nineteenth and especially the twentieth century. The retreat of labour in most of these countries in the last few decades has wiped away much of this landscape, just as a tsunami strips bare of trees the land it engulfs.

If there is a crisis of representation, as Chantal Mouffe terms it, then it starts with the decline of the unions. The centrist politics of the 1990s and 2000s is surely the outcome of that decline, not the cause of it. And when the movements that however imperfectly gave working-class people a voice in daily life disappear, the silencing of their political voice is not far behind. To take the aquatic metaphor further: when the land is stripped bare of trees the soil starts to erode away. Bonds of solidarity among so-called ordinary people erode in much the same way. The remaining soil may well host the weeds of right-wing populists. They are less likely to nourish political movements of the left.

Seen from this angle, left populism appears as a counsel of despair. The working class is too weak or small or declining or fragmented to serve as the base for a challenge to the elites, however defined. In that case, rhetoric and a certain mode of discourse must substitute for the social weakness of “the people.” But rhetoric is a weak basis for a lasting political movement. It can be subverted from the right. The novelty can wear off. With no common bond but language the enthusiasm and the solidarity necessary for any movement on the left can easily dissipate. And there is always, as with the American populists of the nineteenth century, the danger that those closer to the centre can simply adopt the same rhetorical garb, absorb many of the people involved, and end up by achieving nothing but the disillusionment of people desperate for real political change. If solidarity is not restored in daily life, it will not last long come election time.

The point here is not that slogans or discourse are unimportant. There are good ways to say things and there are bad. Like the arguments of a trade union representative to management, the better they are, the better the outcome. But they are not sufficient. Bad arguments can sometimes work with enough people behind them. Brilliant arguments make no difference if made by an army of one. By all means oppose the people to the elites if it helps to win elections, but do so in the knowledge that “the people” will fragment if the day-to-day foundations of solidarity are absent.

To restore those foundations we must rebuild the labour movement. In Britain, that means supporting new unions among precarious workers such as the Independent Workers of Great Britain, United Voices of the World, and other similar organisations. It means supporting older unions, from RMT in their battles over train guards to the Bakers’ Union at McDonalds. It means building real international alliances, as the Knights did, with workers in other countries. Amazon and other global giants span the world, and will not be stopped by the action of “the people” in this or that isolated place. There is no point bringing the left to power if it only means populism in one country.

This might not be an electoral strategy in itself, but it is the best way to improve the fortunes of the left in the longer term. It gives stability to a left-populist coalition that would otherwise have none. It gives the people a voice even before a parliamentary majority is won. That, I hope, could be a lesson from the Knights of Labor.