This week The New Pretender republishes the following article by Omer Tekdemir, and call to discussion and debate from our comrades writing in openDemocracy. Initiated by Spyros A. Sofos and Omer Tekdemir, RETHINKING POPULISM seeks to explore the question of populist politics and theory anew. At a time when new political actors are mounting electoral and increasingly systemic challenges to contemporary democracies in the name of the people, there is little consensus in what the phenomenon is among academics, political activists and citizens alike. openDemocracy has been featuring articles on populist phenomena for some years (Mudde, Rovira Kaltwasser, Mouffe, Marlière, Pappas, Skodo, Sofos, Stavrakakis and Katsambekis, Gerbaudo, Gandesha, Tamás to name but a few) and has been successful in stimulating a recurring interest. But despite or perhaps because of the extensive and thought-provoking research on populism, the term has come to denote a range of widely diverse phenomena. Sofos and Tekdemir aim to bring together voices that don’t often interact, either because they belong to different fields of work, or as a result of geographical distance, to contribute to a vigorous and constructive debate and the cross-fertilization of different strands within the populism theoretical oeuvre. This is not only in pursuit of theoretical and conceptual clarity, but it is also an issue of practical urgency if we are to develop effective, progressive political strategies.

In this article Tekdemir, taking Turkey as his political context, asks: How can we make better sense of debates about populism. Can there be a progressive populism? Is populism really a danger for the survival of democracy or a key to democracy’s future?

Spyros A. Sofos in a timely fashion, points out that there is an urgent need for a constructive and dynamic debate on the notion of populism, in order to give a new impulse to the literature and to develop an effective, progressive politics.

I am grateful to Sofos for taking my article as a first contribution in the quest to dissect the incomprehensibility of the concept, critically highlighting the significance of the role of populism in the complex case of Turkey. I do not designate my piece a Turkish case-study, as the nature of Turkishness is one of the chief issues in the hegemonic struggle between the various contending parties: the dominant discourse of Turkishness is that of an elite/establishment that is challenged by the Turkeyness nodal point of the underdogs. But Sofos’s provocative but constructive response has led me to re-think and re-structure my argument on populism in regard to Turkey’s reality and narrative.

However, my response will not be limited to the empirical study of Turkey’s case, nor do I wish to reduce populism to a mere philosophical device. The aim here is to discuss how we think about populism intellectually and make better sense of debates about populism. Can there be a progressive populism? Is populism really a danger for the survival of democracy or a key to democracy’s future?

I hope that this ‘Rethinking Populism’ initiative, will stimulate and boost many populist scholars, activists and stakeholders to become involved in exploring alternatives through transdisciplinary studies. In addition, there are international formations such as the Populismus research project in Greece and the New Pretender in the UK and Ireland, an online journal committed to developing a theoretical approach to left-populist politics, to promote left-wing populism and the model of radical democracy through an empirical analysis of populist ideologies in the global context.

Rather than de/re-construct the definition of populism which is a complex and ongoing task in the field among prominent scholars such as M. Canovan, D. Howarth, E. Laclau and C. Mouffe, C. Mudde and C.R. Kaltwasser, J-W. Muller, F. Panizza, S. Sofos, Y. Stavrakakis, P. Taggart, and R. Wodak, many of whom Sofos has already mentioned, my aim is to produce some insightful arguments.

Constructing a populist aesthetics or de-popularising populism

Many academics, but particularly journalists, easily tire of using the buzzword of populism. For instance, Roger Cohen, an opinion columnist writing in the New York Times on 13 July 2018, proclaims: ‘let’s do away with the word “populist”. It’s become sloppy to the point of meaninglessness, an overused epithet for multiple manifestations of political anger’. The term populism has been abused and has therefore lost its meaning due to a reckless use which fails to make theoretical sense, whether due to misunderstanding, misapplication, or a lack of analysis and knowledge. Every day we see a number of news items about populism in the mainstream media.

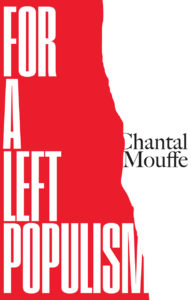

But as Sofos has pointed out, and I now have a chance to clarify, it cannot be the case that any collective action, widespread opposition, popular mobilisation or political issue related to the people should be labelled populist and not all political parties should be assumed to deliver or practice different forms of populism. However, as I have already mentioned, it is not my intention here to enter the terrain of accurate definitions of populism. I echo Mouffe when she says: ‘I would like to make clear at the outset that my aim is not to add another contribution to the already plethoric field of “populism studies” and I have no intention to enter the sterile academic debate about the “true nature” of populism.’

Right-wing populist parties

In contemporary international politics, since the era of post-Fordism, neoliberal capitalism has been in an organic crisis and for a while now it has had a problem in regenerating itself, which makes it very difficult for the hegemonic power to bridge the gap between liberalism and democracy in the global political terrain. This dissonance was exposed and analysed by Carl Schmitt (2007) in The Concept of the Political, where he claimed that liberalism (individual freedom) denies democracy and democracy (collective demand) does not fit with liberalism. Currently, as a result, we see numerous authoritarian neoliberal governments at play in the international arena (e.g. Putin’s Russia, Modi’s India) shifting bourgeois democracy towards conservative authoritarianism. Hence, for Cas Mudde, populist upsurges are a response to undemocratic liberalism.

This tension creates a trust issue among people in representative democracies, leading them to lose their interest in politics (a basic example being the very low turnout in elections). The mass of ordinary people increasingly believe that they are not represented by the centre (left and right) political parties in the democratic system. The M-15 movement in Spain had a banner which said, ‘we have a vote, but we don’t have a voice’, and the title of the UK Labour Party manifesto cries out ‘for the many, not the few.’ This has led the multitude to seek an opportunity to express themselves through channels different from traditional political institutions. Hence, the public space, from Occupy to the Arab Spring, has become an important ground for these new movements in which to raise their voice and to claim that ‘we’re here and we exist’. But the trap here, as with the different forms of populist movements, is to generalise by putting all these movements into the same pot. This ignores how they are shaped in different ways by ideology, class, race, religion, and gender and also mobilised by different objectives and motivations.

Within this global zeitgeist, right-wing populist parties in particular have started to establish themselves as means to fill this hegemonic vacuum by claiming to be a ‘real alternative’ in the crisis of liberal democracy. However, it is essential to make a distinction between this far-right or right-wing populism and far-left (perhaps, for example, orthodox Marxist) and left-wing populist parties, although as Katambekis and Stavrakakis (2013) argue in their piece for openDemocracy Populism, anti-populism, and European democracy: a view from the South the right-wing might to better characterized as ‘populist’ rather than racist, authoritarian or outright fascist.

Right-wing populism as a political enterprise is part of a democratic power struggle that offers a different hegemonic project (although it excludes wider identities, for instance, immigrants, Muslims, LGBTQ,s etc.). The right-wing operates in democratic institutions and employs a populist strategy, mostly in a post-truth and anti-intellectual guise, to gain a hegemonic power within the democratic paradigm. It does this through accepting basic democratic rights. This construction of a collective will (e.g., the people, demos, citizenship) and their hegemonic antagonistic articulation are essential elements for us if we are to understand the notion of populism from the perspective of the Essex School’s political ontology. From this perspective, the formation of political blocs, and hence a chain of equivalence (an historical bloc), is good practice in seeking to build a counter-hegemonic culture as a form of common sense (or a nodal point) for constructing a collective identity.

Left-wing populism

Laclau and Mouffe’s theory of left-wing populism does not just arouse interest within the populist literature but is also a blueprint for populist actors (i.e. Kirchner in Argentina, Syriza in Greece, Podemos in Spain, or the right-wing Le Pen in France) who attempt to challenge the status quo by the interpellation of ‘the people’ (here described as an empty signifier). Within this Laclauian and Mouffeian legacy, populism depicts the logic of the political as a discourse – not a classic text but a set of discursive practices, whereby what Ludwig Wittgenstein (2009) in his Philosophical Investigations calls a ‘family resemblance’, is deployed to epitomise the people.

I am aware that the reliance on a charismatic leadership among the populist actors and groups required for such a scenario creates a potential threat for democratic institutions and representative politics, one that might end up with an illiberal majoritarian regime that could be characterised as authoritarian. Mouffe states that ‘it is very difficult to find examples of important political movement without prominent leaders… Everything depends on the kind of relationship that is established between the leader and the people.’ I think the vital point here is the question of ‘what leader in what kind of populism?’ In a reforming and inclusive populism, the leadership is an agent of progressive populism if it promotes egalitarian libertarian principles. This requires ‘intellectual and moral’ guidance and a leader who vigorously represents an inclusionary policy within the grassroots movement that mounts a counter-hegemonic challenge to the existing hegemonic order.

The dynamic nature of collective identity means that leaders cannot narrowly define what constitutes ‘the people’. Bloc politics are variable and the regulation of the balance of power between the elements of the bloc and the leadership must be based on a more horizontal, and less vertical, relation between them. If the leadership does not actively pursue and encourage democratic and emancipatory values, then the system is not democratic and there is no possibility of talking about a meaningful populism.

The role of collective passion, such as that belonging to a nation, religion, gender, or for example in the expectation of economic stability and sustainable development and their common affects, cannot be ignored in democratic politics. In a representative liberal democracy and neoliberal economic system, the left needs to accept these emotional states of the masses such as hope, anger, vulnerability, etc. These need to be taken into account in creating a new discourse, a culture that through counter-hegemonic activities (such as art, film, music) can attract diverse people and combat the negative image of the left in any neoliberal hegemonic formation. The left, therefore, instead of subjecting the negative aspects of populism to a rational critique, need to fill its content with egalitarian and libertarian values.

How can we reclaim populism for the left? Left-wing populism needs to construct ‘the people’ through a unity of progressive horizontal (social) and vertical (political) movements without excluding those who debate the ethico-political principles of equality and liberty for all. Within the same political bloc, leftists must create a symbolic radical democratic ground that allows for an agonistic negotiation on the scope and nature of equality and liberty, that is an agonistic struggle between various hegemonic projects for the construction of ‘the people’.

But as Katsambekis and Stavrakakis argue: ‘this does not mean that left-wing populisms now become a panacea; that, from now on, they would necessarily have to be (unconditionally) accepted as having a positive impact on democracy. Not at all; there are no guarantees here’. At the very least, the recent experiences of left-wing populists in Latin America (e.g. Kirchner, Morales, Correa from a legacy of Peronism, and Chavez) and Europe (e.g. Syriza, Podemos, La France Insoumise) do succeed in challenging neoliberal hegemony, and its discourse of ‘there is no alternative’ (TINA), to create a hope for an alternative politics.

Most of them, however have failed in other ways. According to Katsambekis and Stavrakakis ‘our role today as social scientists is neither to dismiss populism tout court, nor to idealize it, but rather to critically engage with both populism(s).’ It cannot be predicted here whether the left-wing populist project will succeed in the future, but as Mouffe concludes ‘there is, of course, no guarantee, but it would be a serious mistake to miss the chance provided by the current conjecture.’

With Sofos to think against Sofos

The two approaches of Sofos’s analytical point of view and my theory, while they seem to differ considerably, need to be linked in order to devise an alternative conception of an emancipatory, inclusive left-wing populism. This, moreover, immediately raises a debate over whether our accounts should encourage the individual to embrace a popular sovereignty. Is it possible to politicise politics under a neoliberal capitalist regime; and if so, what type of post-populist strategy can be used to prevent authoritarianism?

Sofos touched upon this when he wrote that ‘what we need, however, is a rigorous and constructive debate on how we can develop an understanding of populism that has a critical edge and a conceptual definition that adequately situates the latter vis a vis other concepts and conceptual frameworks’. For my part, I am not suggesting that my theoretical account should be seen as a recipe, instruction manual or template to be used for various cases. I am not proposing a universalistic, or holistic approach that can embrace all populist examples, although I do not deny the possibility of a transnational left-wing populist solidarity. Rather the challenge for left-wing populists will be to re-articulate the neoliberal nationalist approach in a progressive form that can go beyond nation state borders (including collective historical memory, symbols, self-interest etc.) and narrow definitions of ‘the people’, the nation, on the international stage.

My intention, therefore, rather than seeking a total consensus on what populism means; is to offer a Mouffeian agonistic approach for the purpose of our conversation, to carry on seeking to describe populism within an academic debate characterised by a ‘conflictual consensus’ (that is, a negotiation of conflicting views within a peaceful framework). Whenever I find opportunities to tête-à-tête with prominent scholars of populism, like Chantal Mouffe, Yannis Stavrakakis, Francesco Panizza and Ruth Wodak, my aim is to discuss, learn and help produce an anti-essentialist understanding of the concept.

As a result, I have come to the conclusion that types of progressive populism can enter the struggle within their own geopolitical arena and gain hegemonic power, but that they can also synchronise with other progressive democratic populist actors on an international platform, and that in the process they may transform the international system in a progressive direction away from the dominant transnational neoliberal institutions.

Returning to Turkey

In Turkey, we witness a problematic majority consensus at the centre of Turkish politics, established on the grounds of unity (e.g. one nation, one flag, one state and even one religion), security (the internal and external ‘terror’ threat, i.e. the Kurdistan Workers Party-PKK and the Democratic Union Party-PYD), and the continuity of the state (motivated by the Sevre syndrome – a trauma of division which emerged after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in anti-imperialist discourse). This problematic consensus or national will rests on an ideal model of the Turkish citizen defined as a Sunni-Muslim Turk (whether secular or devout), a nationalist and a stateist – an identity that may be ‘voluntarily’ accepted even though it is one not ‘originally’ held (all this is comprehensively explained by Barış Ünlü (2018) in his recent book, Türklük Sözleşmesi).

Under such a status quo, between the centre-right as represented by the Justice and Development Party (AKP) and the secular centre/left as represented by the Republican People’s Party (CHP), the collective demands of minorities such as Kurds, Alevis, non-Muslims and LGBTQs are excluded. As a result politics fails to provide them with the democratic channels to seek redress for their discontent. This political alliance, I would argue, creates a post-political situation that blurs the lines between political differences, for example there are no major divisions between mainstream parties on Kurdish linguistic rights, the recognition of cemevi, LGBTQ equality and so on.

According to Mouffe this look like a dissimilarity between coca cola and pepsi cola. However, this situation is challenged by what I might describe as a new cocktail in the form of the discourse of Turkeyfication, new life, great humanity and great peace epoused by the People’s Democratic Party (HDP). Theirs is a promotion of a radical pluralism that embraces differences in an agonistic context. This provides a political environment that allows the traditional antagonistic enemy relation to be transformed into an agonistic adversarial one. However, it is crucial to add that this idea of the ‘friendly enemy’ does not aim to eliminate conflict, so much as to sublimate it.

In this way, the left-leaning HDP has used a strong ‘libidinal investment’ (passion) that does not reduce politics to the purely logical and has even modified Kurdish nationalism in a progressive way. Moreover, on Ince’s personal initiative, the leadership of the CHP in the run-up to the June 24 election also employed a strategy that was similar to the extent that it stretched beyond his own party affiliation and identity. These two disconnected left-leaning agents attempted to redraw the political landscape at a time of post-political blurring by offering a new expanded notion of ‘us’ and ‘them’. Ince’s (and the CHP’s) ‘nation alliance’ was an opportunity for a new social contract with the HDP’s radical democracy bloc as it incorporated a wider range of society that included Kemalists, Islamists and Turkish nationalists.

This is different from the arguments made by E. Erdoğan, T. Erçetin and J. P. Thomeczek (whom Sofos references). I disagree with the idea that the Good Party (IYI) is a populist one, or that the Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) or the Felicity Party (SP) have cultivated their own populisms. They are better seen as part of a populist bloc under a strong charismatic leadership. Three blocks (the public alliance, national alliance, and radical democratic) set out to construct ‘the people’ according to their ‘agreed’ ideological perspective by mobilising different segments of society. In particular, the populist leadership of R. Tayyip Erdogan, Muammer Ince and Selahattin Demirtas, each taking on a different style (authoritarian, devout, charming, charismatic, humanist, sympathetic, or whatever), enabled these leaders at different times to create their alliances, whether this was based on a ‘chain of equivalence’ or a ‘chain of interest’ in a friend/enemy cleavage against the ‘establishment’. Each of them also defined the term in a different way.

These political emotions (collective passions, not individual sentiments as in the Freudian sense of ‘libido’) perform an important role in the construction of the demos as a collective will. Therefore, ignoring or denying this political passion, through positivist rationalism or orthodox Marxist reductionism, would be a serious mistake for any left-wing radical plural democratic project. This is not to say that such a post-Marxist stance is against the reality of class-oriented struggle. On the contrary, it appreciates working-class struggle within the broader radicalising process of liberalisation and democratisation that it proposes. To do otherwise means abandoning the public sphere to right-wing populist party domination, as in the case of the AKP among other global examples. That is why the 24 June election in Turley was an important one. It was perhaps the last stage of populism to emerge as a confrontation between conservative and progressive populism.

In my view, populism is not a thin ideology and is formed in different styles. Gezi was an impromptu movement developed in multiple struggles and through populist discourses of emancipation. Further, between its distinct components a common ground emerged in the shape of democratic (including economic) demands and the demands for the popular sovereignty of the people not limited to any unitary identity; rather the popular will was formed in terms of being against the establishment (for more details, see my work with Oğuzhan Göksel on Gezi, 2018).

The ‘Gezi spirit’ was an example of agonistic pluralism where antagonistic enemies (Kurds, nationalists, Alevis, leftists, Kemalists, Islamists, petite bourgeoisie, working class, LGBTQs, feminists etc.) transformed their conflict into an adversarial as opposed to enemy relation, enabling them to discuss their disputes on a symbolic radical democratic ground. As a non-ideological, spontaneous, and uneven social rupture, they did not need a populist leader.

In this respect, in our rethinking of populism, we need to make a distinction between a social movement and a political party. On the one hand, scholars like Antonio Negri and Michael Hardt, along with some other post-Operaist theorists such as Paulo Virno, advocate an exodus or withdrawal from existing representative democracies in pursuit of democratic ends or suggest a revolutionary course which pursues an absolute (direct) democracy. But in practice, we have witnessed the temporary nature of the square movements (e.g. Indignados, Aganaktismeni, occupy, Arab Spring and Gezi). Once they abandoned the public space, this led to the disappearance of their collective anger.

Instead, in a representative democracy, the collective passion needs to be mobilised by a political party designed to raise the voice of the voiceless in the system. So, some of the components of these movements have collaborated (but not merged) with left-wing populist parties (e.g. Syriza, Podemos, HDP) to make explicit their demands via conventional politics. Without this, right-wing populist parties would dominate the system while they would have no parliamentarian platform. Consequently, they have synergised their activities with a political party (Gramsci refers to these as the ‘modern prince’) to seek hegemonic power by using a strategy of ‘engagement with’ democratic institutions in a war of position. Laclau and Mouffe argue that this can profoundly transform liberal democracy along radical (leftist) principles. This tactic of passive revolution, in my view, is a fitting description of the HDP and Gezi relationship.

The post-democratic era of Turkish-Islamic populism

The conservative democratic government of the AKP which was once the champion of the principles of liberal democracy, multi-diversity, the constitutional state and civil politics (against the military tutelage) has now been transformed and instead introduces a state of emergency and rule by decree. The newly absolute sovereign regime lifted the state of emergency after two years on July 18, but according to Fotis Filippou, Amnesty International’s deputy Europe director, this will not suffice to reverse the political crackdown. The new authoritarian neoliberalism continues to criminalise, terrorise and securitise all democratic plural demands. It is a post-hegemonic conjuncture, the beginning of a post-populist moment in a post-democratic era. Consequently, as a result I would not hesitate to claim that the AKP is no longer a populist party. I offer two reasons.

Firstly, I would argue that the AKP has become a centre-right party through being in government for the last sixteen years and by embracing the status quo (not an underdog any more). You have only to look at the institutions constituted after the 1982 military coup such as the Higher Education Council (YOK), and illiberal state bodies such as the Radio and Television Supreme Councils (RTUK) and Director of Religious Affairs (Diyanet). In this way the AKP has come to represent the prevailing establishment and elite. This creates a difficulty for the AKP administration in that it does not allow the formation of a discourse and the construction of an ‘us’ in an open environment. Instead populist discourse and practice is generated amongst the oppressed, victimised, and excluded masses who stand against the dominant power.

The AKP leadership fabricated friend/enemy cleavages by reference to the 1930s Kemalist era (since contemporary Kemalists were ‘weak’ and could not offer a strong opposition against Erdogan and the AKP) and by blaming international and imperialist powers, including the financial–interest lobby, for working against the ambitions of the ‘new’ Turkey’s in its project to become a regional, and, moreover, an internationally, powerful state. Within this context, ‘the people’ are now constructed in terms of a narrow nodal point (Turkishness and Sunni-Muslimness). With the AKP in coalition with the MHP, populism can no longer find a way to reach diverse people as it tried to do in the earlier days of the AKP administration.

The second factor is the lack of a democratic environment. The current majoritarian and ‘national will’ understanding of democracy has de-politicised politics by eliminating the opposition and monopolising the media. Moreover, the renewed armed conflict with the PKK in 2015, the failed coup attempt by the so-called FETO (Fetullahist Terror Organisation, a transnational Turkic-Islamic sectarian group) in 2016, and the military operations beyond Turkey’s borders, such as in Afrin north of Syria and the Kandil Mountain in northern Iraq in 2018 against the PYD and PKK, all have helped to create a zombie politics.

This post-political situation has also harmed the Gramsciam equilibrium between consent and coercion, with almost half the members of society withdrawing being left to express their anger in passive or aggressive resistances such as during Republican Meetings, in the Gezi protest, their outrage at such things as the Soma incidents, Roboski massacre and Islamic State’s (IS-ISIS/DAES) deadly suicide attacks, and the March for Justice. In response the authorities have only employed force (justified as against ‘them’) to hold onto its power. This creates tension, division, and polarisation, and constantly raises issues of legitimacy within an overall politics of fear.

As a closing statement, I am convinced that populism represents an important dimension of democracy and the politics of hope. Democracy, which implies people’s power, requires a demos and not a homogeneous nation dominated by notions of one nation, religion or ideology in an essentialist way. However, in our case, the future of democracy in Turkey depends on the development of democratic institutions (including the judiciary), liberalisation of politics (including a sustainable economic development), peace between the state and society (including within Turkish society and its foreign relations), and a new citizenship that goes beyond a technical legal tie, based on a social contract. This requires fostering an agonistic multivalent debate on alternative projects and the re-democratisation of the country.

Invitation to a debate

from Spyros A. Sofos

Omer Tekdemir’s response above to some of the questions I have raised in my reflections on the need for a populism debate, is a foretaste of the series of exchanges that openDemocracy will be hosting and encouraging over the next few months. Our aim is not to support a series of monologues but a series of fruitful discussions. For our part, we want to contextualize the ideas of our contributors, and draw on past contributions on populism published by openDemocracy to help us do so.

This is why this week we have selected from openDemocracy’s archives an article that attempts to trace the conditions for the emergence of populism by Seren Selvin Korkmaz and Alphan Telek; an interview given to Antonis Galanopoulos by Paolo Gerbaudo on the possibility of populism without leaders; and a primer on populism written by Cas Mudde, one of the most influential theorists in the field. We also begin to focus on one of the most significant debates relating to populism today: Chantal Mouffe’s contribution evolves around the importance and feasibility of a populism of the left inspired by an agonistic ethos, something echoed in Tekdemir’s contribution too. To this discussion, Marina Prentoulis and Lasse Thomassen bring their reflections from back in 2015 on SYRIZA’s political success in the Greek elections, when they argued that this was the time for a Left populism that would transcend national boundaries in Europe.

This selection of Related Articles hardly does justice to the considerable array and richness of the debate (within and beyond the confines of openDemocracy). But via this selective contextualization, we hope to tempt openDemocracy’s readers and contributors to bring their comments and interventions into the discussion. By September we will have a partnership page. But we welcome your participation from now on.

Please contact me here: spyros.sofos@cme.lu.se

Spyros A. Sofos

Rethinking Populism can be found on Facebook here: https://www.facebook.com/rethinkingpopulism/