This winter, I voyaged to Belfast for the first time. As an outlander, this trip profoundly changed my views on the Northern Irish conflict and the question of Irish Unity. In this article, I narrate my journey to Belfast before proposing a few tactical orientations for a United Ireland. Although these remarks are those of a foreigner, whose political experience was gained in France and Scotland rather than in Northern Ireland, I hope the following lines can be of use for those who believe in a different future for the six counties.

My journey to Belfast

I was on the deck when the Ferry neared the coast of Ulster. My head was wobbly since we had left Scotland — the time had come for fresh air and scenic views. Forward, the harbour, the roofs and the modern towers of Belfast city offered one of those rare and poetic images which enable the gaze to unify, in one, fugitive glance, the life of thousands. It was as though the incredible complexity of the place, with its layers of hatred piled over centuries of strife, suddenly flattened under my eye. Belfast from the sea seemed an effortless harmony of red bricks and green hills —softly whitened by a Christmassy snow.

Although I was a complete foreigner to Northern Ireland, which I was visiting for the first time, I knew, however, that my vision was only a delusion. Belfast was not a city of harmony. Its civil peace was but a civil truce and its boisterous party animals could not cover the silence of their scarred and curfewed neighbours. Certainly, as a republican Frenchman living in Scotland, I was aware of this. Even more so, I knew where I stood. From France, I drew a strong contempt for crowned heads as well as an earthly fondness for ancient, Catholic churches. I also took special pride in the role played by my country in 1798, when it had answered the supplications of the Irish Republican Wolfe Tones and sent a fleet of six thousand Frenchmen to free Ireland from British rule. The failure of the expedition notwithstanding, I loved to remember that the origins of Irish republicanism were so tightly connected with the French revolutionary epic. Besides, from Scotland, I knew of the humiliations and discriminations suffered by generations of Irish immigrants which had once landed on the banks of the Clyde, the Forth, and the Tay – the same wretched cohorts which in their numbers had provided the early Scottish Labour movement with dedicated rank-and-files and leaders. Needless to explain further, I approached Belfast with a strong “Green” prejudice.

Half an hour later, the Ferry entered Belast harbour. I landed and took a shuttle for the City Centre. There, I took no heed of the few hipsters that passed next to me and made my way to my hostel. In my room, I looked up a map of the City. As a political tourist, I would not waste my time in the commercial Centre. Instead, I would focus on the Catholic patches of West Belfast. There, I would feel at home, on the right side of the barricade —that of tricolours, red flags and Easter Rising murals.

Little did I suspect, however, that the next few days would challenge some of my strongest held pre-conceptions.

The following morning, I got up early and walked westward. My boots on a thin coating of icy snow, I stumbled through the loyalist areas of Jubilee and the Donegal Road, grimacing at the countless Union Jacks and UVF frescoes [Ulster Volunteer Forces – a loyalist paramilitary organisation] which stood on my way. After a few minute walk beyond the A12 highway, I merrily entered the Republican zone with its Irish slogans and its murals of Bobby Sands, Karl Marx, Nelson Mandela and other Freedom Fighters. Going down the Falls Road, I stopped at the Sinn Féin souvenir shop where I bought a few books on the 1798 rising. This, certainly, was genuine republican and Internationalist tourism.

After lunch, I walked up to the Divis Tower, a massive red building that was used by the British army during the Troubles to survey Catholic neighbourhoods. There, I joined a small group of visitors on a three-hour ‘Political Tour of Belfast’. The first part of the tour was guided by an ex-IRA prisoner and current Sinn Féin member who had learnt Irish in jail, with Bobby Sands. His charismatic and assertive voice quickly led us away from the overvisited murals of Falls Road to enter the maze of Catholic cobbled streets and red-bricked council-estates where the real tragedy of the Troubles had occurred. After walking down a few yards, our guide stopped in front of an old mill where both Catholic and Protestant workers were employed during the interwar. The old activist explained that, back in the day, the Trade Unions had managed to overcome sectarianism by organising strikes for better working conditions. Like the old Trade Unions, our guide explained, ‘‘Sinn Féin is a radical, non-sectarian party which stands for all working people”. Certainly, I thought, this was the only sensible position to ever win Irish Unity —the same position the United Irishmen had held in 1798.

A few minutes later, we passed in front of a primary school. Our guide proudly depicted it as a bilingual institution, where pupils learnt both English and Irish. He went on to express his support for an Irish Language Act that would enforce the teaching and speaking of Irish or ‘Gaeilge’ in Northern Irish schools and State respectively. At that point, I remembered having read that loyalists opposed such a Language Act because they accused Sinn Féin of not acknowledging Ulster’s own linguistic tradition —that of “Ulster Scot” (a Northern Irish dialect descending from the Scottish dialect or “Broad Scots”). This, obviously, triggered my Scottish self. In spite of all the respect our guide inspired me, I asked him, semi-mischievously: ‘In Scotland, Scots and Gaelic language activists work hand in hand to promote Scotland’s cultural heritage, how come this is not the case here?”. Apparently embarrassed, the ex-IRA prisoner answered: “Ulster Scots is just a DUP invention to counter the Irish Language Act. To us ‘Ulster Scot’ is not a language, it’s just bad English’. Unconsciously, by dismissing Scots as a coarse and improper tongue, our Republican guide had just embraced what in Scotland would sound like a staunch unionist argument. Here was an irritating contradiction for an anti-sectarian and radical party which embraced an elitist standpoint on language to antagonise the popular dialect of Ulster.

Soon, we crossed the gate of the Catholic neighbourhood. It was four o’ clock. Three hours later, this entry would be closed for curfew, preventing any circulation between Catholic and Protestant communities before seven o’ clock in the morning. At the gate, we were joined by our second tour guide. He was a former member of both the UVF and the British army, and a survivor of assassination attempts. After shaking the hand of the ex-IRA prisoner, who was affecting a Good Friday-like smile, our new guide took us for the second part of the tour, towards the Loyalist tenements of the Shankill district.

Needless to say, I felt less inclined towards our Protestant guide. His discourse essentially consisted in blaming the IRA for past attacks and past traumas. Overall, he failed to convey a vision for the future of Belfast and Ireland. Instead, he merely displayed the frightened face of a besieged community.

Nonetheless, a rapid comment of his did much to alter my views on the Northern Irish question. As we walked in a Protestant council-estate (which looked very similar to its Catholic counterpart) our guide described the distressing evolution of the area during the past two decades. “All those who could afford to live away from this mess have moved out. You see this street, these houses, they are packed with those who were too poor to leave – jobless folks and single mums mainly’’.

All of a sudden, his comment shed light on the overall vacuity of my own sectarian prejudices. Except for different hues on their flags and murals, both communities of West Belfast seemed much closer in style, desolation and living standard than the gentrified centre I had left in the morning. Anywhere else in Ireland and in the UK, such areas as the Catholic and Protestant neighbourhoods of West Belfast would simply be the likes snobbish imbeciles name ‘’dodgy schemes’’ and mainstream media dismiss as ‘’losers of globalisation’’. Certainly, the likeness of Catholic and Protestant communities was a rather recent phenomenon. Such was not the case, for instance, in the 1960s, when Catholics were still discriminated and often expropriated from their home. Today, however, West Belfast appeared far more homogenous than I had imagined —homogeneity of past traumas and poverty.

One hour later, our Protestant guide concluded his tour on a former IRA bombing site, on the Shankill Road. Frozen, after many hours walking over ice and snow, I swiftly made my way back to the hostel. Bewildered by what I had just heard and seen, I forgot, once again, to pay much attention to the procession of the multicolour lights, billboards, malls, fancy towers, vegan bars, hipster beards, and bevvied students of Belfast City Centre.

The following day, however, I spent more time in the town. I walked up the many stairs of Victoria Mall, climaxing in an incredibly modern and Dubai-looking glass dome. I went down and had a cigarette with my friend and her group of jovial hisptery chums. I wandered in the bookshops surrounding Queen’s university, eavesdropping on the conversations of polished academics.

In total, I spent only two days in Belfast. Yet, it feels like I voyaged in two different worlds.

24 hours later, I was gone —back on the reeling ferry —back to Scotland —back to my home of Dundee —in a similar city of plebeians, students, and rival football clubs, but where most workers, students and football fans had long lay down their arms and casted their votes for Labour, SNP, and Independence.

Social geography of Northern Ireland

It took me time to digest my Belfast experience. It caused me to read and reflect a great deal—reflect on the old and new divisions of the city —reflect on class and nationhood —reflect on Irish Unity. Here are the few thoughts which I came to formulate, as a result. These thoughts are those of a foreigner who can hardly figure out the extent of the suffering that were (and still are) endured by common Northern Irish folks. I hope, however, that these thoughts will be at least of some use for those who want suffering, division, and poverty to cease across the Irish Sea.

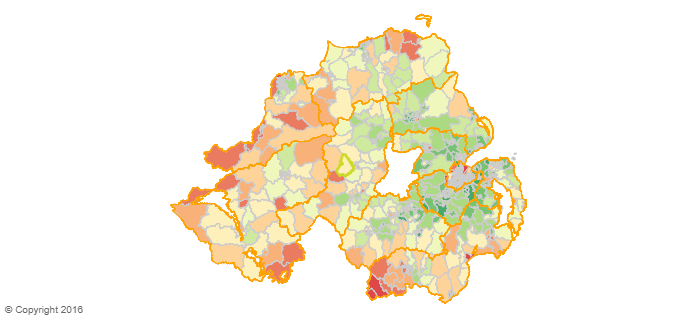

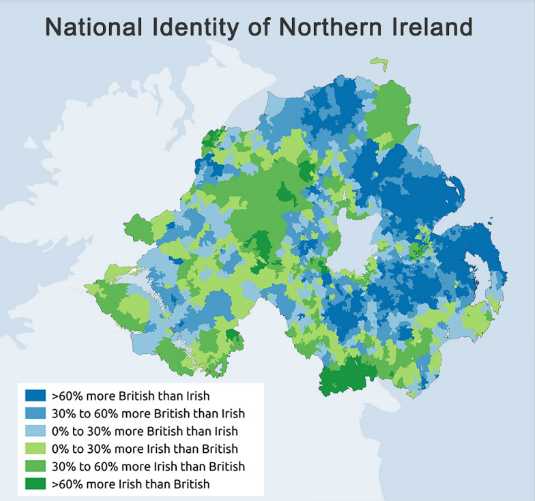

More than ever, it seems, contemporary times offer the opportunity to overcome sectarianism and unite Catholic and Protestant working-class communities around a radical programme. Indeed, the time is gone when Protestant mill owners could dismiss Catholic job seekers and put the egotistical welfare of their own community before the interest of all the citizens of the six counties. Only five of the twenty biggest companies in Northern Ireland are actually based in Ulster (including Moy Park, Northern Ireland’s top employer whose CEO, Janet McCollum, began her business career in Coca Cola). Whereas 1960s Marxists from the Official IRA could objectively link Northern Irish capitalism to the Protestant dominion, the current situation appears much more complex with both protestant and catholic communities suffering from deindustrialisation, globalisation, and gentrification.

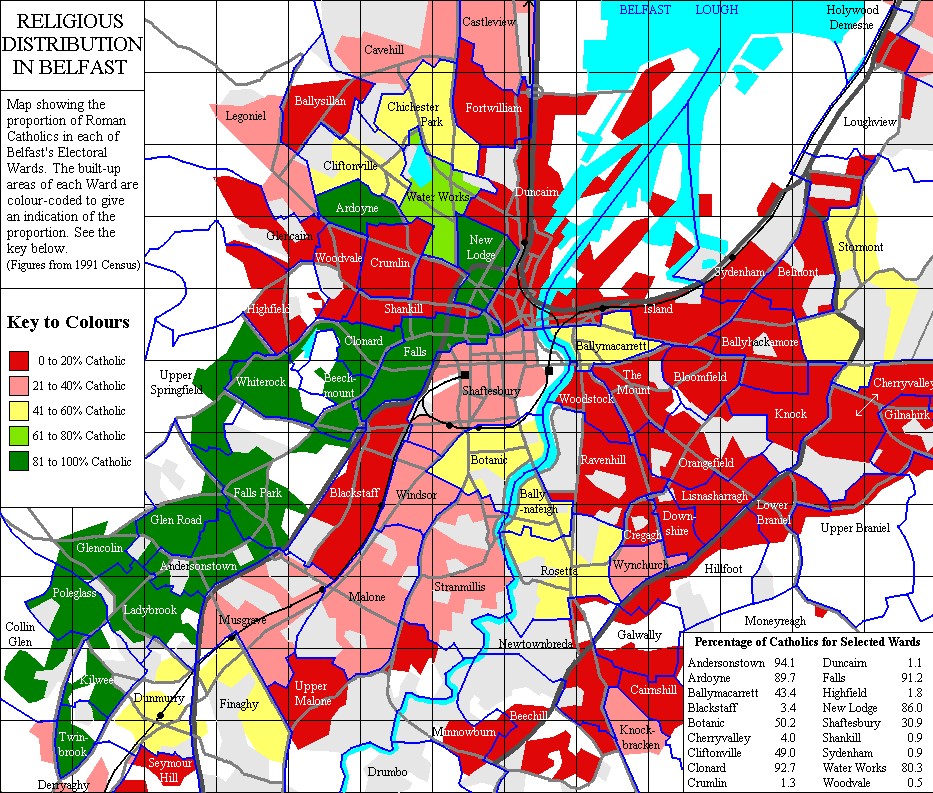

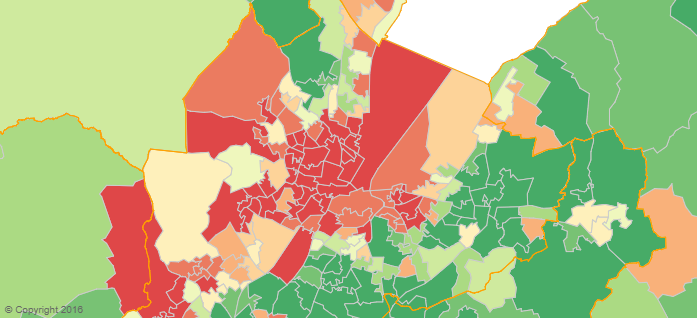

Certainly, the wealthiest areas of Northern Ireland are still Protestant and Loyalist. This is the case, for instance, of East Belfast or Lisburn and Castlereagh, which are all DUP strongholds. However, according to a 2017 NISRA survey, the Republican and Loyalist districts which I visited (Falls and Shankill) account for the 29th and 16th most deprived areas of Northern Ireland, respectively. A similar analysis applies to Derry where the Catholic Diamond district and the mostly protestant area of Ebrington respectively rank as the 11th and 24th poorest areas of the country.

Such figures reveal the growing social disparities at work within the Protestant community. On the one hand, the suburban Protestant middle-class has adapted to globalisation, albeit losing much of its control over the country’s globalised economy. On the other hand, the urban Protestant working-class has been increasingly marginalised by deindustrialisation and gentrification. It now stands alone, bogged down its own sectarianism, face to face with their equally poor and sectarian neighbours.

The thin path to Irish Unity

This situation provides Sinn Féin with an unprecedented opportunity to prove its anti-sectarian values and unite the People of Northern Ireland beyond religion. Time has come for Republicans to indulge in a combination of populist and divide-and-rule tactics. Let me explain myself.

Ireland will never be united until sectarianism is overcome. No other parties knows this best than the DUP whose only raison d’être is to maintain the sectarian divide across all protestant social classes. In other words, any attempt to effectively break the sectarian barrier and replace it by a cleavage of a social or political kind is in the interest of Irish Unity.

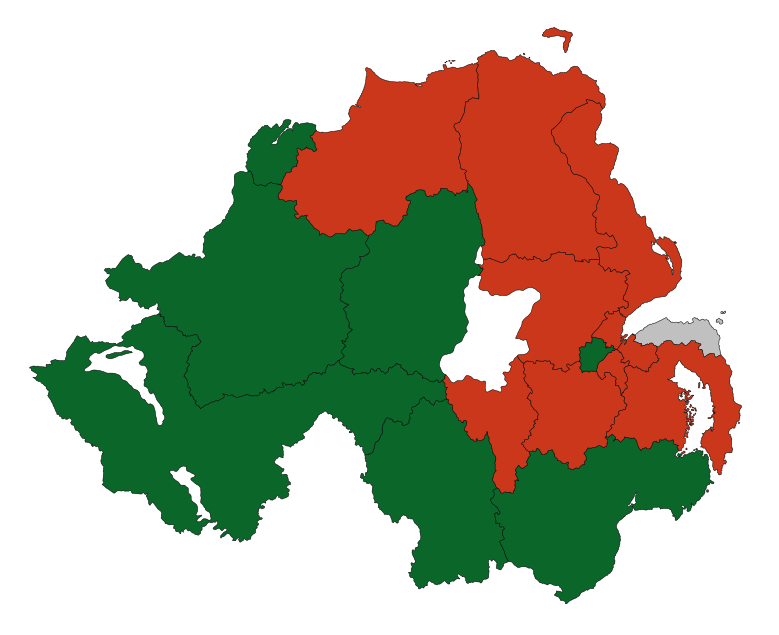

Today, two main options lie ahead of Sinn Féin to circumvent the sectarian barrier and appeal to parts of the Protestant community. The first one, which also seems the more obvious, is given as a result of Brexit. 55% of Northern Irish voters opted for “Remain” in June 2016 —including a large number of middle-class protestant voters. According to Sinn Féin, this could lead pro-European protestant voters to rally the cause of Irish Unity in order to stay in the EU. In many ways, however, there is no clear path from Brexit to Irish Unity. Whereas most Northern Irish people feel strongly about the constitutional issue (with less than 10% “undecided” according to every polls on Irish Unity), the European question is far from triggering the same level of interest. Northern Ireland had the lowest turnout of all UK’s nations in the Brexit referendum—62%. Moreover, abstention was the highest in popular Catholic neighbourhoods, reaching 52% in West Belfast (the lowest turnout of the whole UK) and 43% in Foyle. In other words, the EU might not even be enough of a motive to rally all the Catholics behind the cause of Irish Unity —never mind rallying parts of the protestant community. Indeed, according to a 2017 poll, only 33% of the Northern Irish population would vote for Irish Unity in the wake of Brexit —this is less than the 45% of catholic people who live in the country. As it appears, the Brexit road is a dead-end for Irish Unity.

Instead of wasting time waving the EU flag, Sinn Féin should take Irish Unity seriously and embrace the second option that lies ahead. This one consists in destroying the sectarian barrier to replace it by a populist divide opposing the traditional communities of Northern Ireland to the new, globalised gentry that really rules the country today.

To achieve such a challenge, Republicans must get rid of their own sectarian prejudices. Instead of scornfully dismissing “Ulster Scots” as bad English, Sinn Féin should play the DUP at their own game and acknowledging the importance of Scots in the literary and popular culture of (Northern) Ireland. This means not only conceding an Ulster Scots Act to the DUP (as in the recently aborted Stormont talks) but also undermining the DUP’s monopoly on the question of Ulster Scots. Like any other minority languages, Ulster Scots ought to be defended against the globalisation of language. By standing for Ulster Scots, Sinn Fein would also stand for the protection of the identity of all the Irish —whatever their religion may be.

In a similar vein, Celtic supporters should cease to emulate Rangers hooliganism. Instead, they should open up their pubs, pay their rounds, and fight hand in hand with protestant football fans to maintain decent amateur sport venues throughout the country. Further still, Republicans should know better and stop antagonising popular Loyalist symbols. For instance, instead of attacking such a powerless symbol as the Queen, Republicans should denunciate those who hold real power over Northern Ireland. From casual-contracting multinational firms to London-based companies leading expensive and useless redevelopment schemes in Belfast City Centre (from empty offices to costly student accommodation), there is no shortage of targets for the development of a populist strategy in Northern Ireland.

The main mistake that should be avoided, in drawing a new political divide for Northern Ireland, would be to explicitly turn deprived Protestant areas against the wealthier parts of their own community. The Irish twentieth-century has already demonstrated that Protestant solidarity in Northern Ireland was stronger than class division. To rally the Loyalist working-class and parts of the Protestant lower middle-class, Sinn Féin cannot indulge in scapegoating the Protestant upper-class. This is why republicans should bypass the religious issue by concentrating their attacks on extra-communitarian entities. Unfair housing planning, low wages, expensive university policies, and ruinous architecture projects are not the responsibility of East Belfast bourgeois but that of London and Dublin neoliberal programmes.

It could be tempted, certainly, to add the DUP to the list target list. However, international experiences in France or the United States show that left-wing populists cannot rally former or current right-wing voters by incriminating their former allegiances. Jean-Luc Mélenchon in France and Bernie Sanders in the US have gained ground in working-class conservative areas neither by insulting their audience as ‘racist’ or ‘bigots’ nor by fear mongering about the far-right. Mélenchon and Sanders won over right-wing working-class voters by demonstrating that they could represent them better than any other parties because they had identified the real problem —not the immigrants, not the catholics, not the protestants, but unregulated globalisation and anything goes free market policies.

In short, Sinn Féin should leave alone highbrow “proddies” and the DUP to refashion a new foe —the globalised establishment—likely to concentrate the anger of all Northern Irish communities. Only by doing so, Republicans could pretend to represent the voice of the whole country.

A last mistake that should be avoided, in my opinion, would be to attack the symptoms of globalisation and gentrification instead of exposing their causes. Uprooted and indebted students should not be enemies but allies for a Republican populist strategy. Likewise, vintage-clothed hipsters also suffer from rent increases, dodgy contracts as well as their own incapacity to relate to their foreclosed and marginalised neighbours. Once again, it is the role of the Republican movement to articulate demands between council estates and city centres —for instance, by connecting the lack of affordable social housing with the increase in expensive student accommodation.

To represent the voice of all Northern Irish people, however, Republicans must stop presenting themselves as an oppressed minority. A minority cannot be the rallying unit of unity. It is not enough to be the outpost of Ireland in Ulster territory. If Sinn Féin ever wants to gain the majority of votes in Northern Ireland, it must err away from minority politics and address every Northern Irish citizens, from West Derry to Shankill road and student halls.

Instead of presenting Ulster as Ireland’s problem, Sinn Féin should see Northern Ireland as the place which might impulse the radical transformation of Ireland as a whole. Indeed, Republicans must understand that there is nothing attractive, for a West Belfast protestant, in joining the “Vulture Republic” of Fine Gael —a land of austerity, expensive housing and fiscal optimisation. There is no need to await the improbable birth of a radical model south of the border when Sinn Féin has the possibility to transform Ulster radically, here and now.

By addressing the deprivation of both Catholic and Protestant communities, by defending the cultural identity of all the Irish, by rallying the lower middle class youth, by representing the voice of all the six counties, and by condemning the new, globalised elites that rule over the country, Sinn Féin would have the power to overcome sectarianism and therefore pave the way to Irish Unity.

In 1791, Theobald Wolfe Tones, the Protestant father of Irish Republicanism, wrote:

“To subvert the tyranny of our execrable government, to break the connection with England, the never-failing source of all our political evils, and to assert the independence of my country, these were my objects. To unite the whole people of Ireland, to abolish the memory of past dissensions, and to substitute the common name of Irishman, in place of the denominations of Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter, these were my means.”

Today, more than ever, Tones’ means are the path from Ulster to Éireann.

Further reading:

NISRA survey on deprivation in Northern Ireland.

“Gentrification in a Post-Conflict city: the case of Belfast”, Conor McFall in The New Socialist.