Today, TNP covers a Tayside scandal. This morning, the Dundee Council Licensing Board has met to consider the application to renew the license for Brassica Ecosse, a company that was liquidated in October and left its Dundonian workers without wages for weeks. Cailean Gallagher investigates the background of this outrage and sheds light on the many flaws of the employability initiative led by Dundee City Council.

On the fifth of April this year, in a Dundee council meeting room, an executive chef showed ten unemployed Dundonians a photograph of a glass door. ‘Glass door’, his slide explained. This was the entrance to a brasserie that would soon be opening in Dundee’s new Waterfront development. According to an employability initiative of Dundee City Council called Discover Work, Scott Cameron, executive chef of Brassica, was using the image to explain ‘the exciting opportunities within the restaurant’ and to recruit staff. Six months later the door was locked, the company was liquidated, and many of the young people who attended that training workshop lost their jobs and were left without wages for weeks of work. With Brassica’s collapse, a showpiece of the city’s flagship employability project was shattered.

Like many local authorities, Dundee City Council offers recruitment and training services to new companies. In this case, the Council arranged three unpaid day-long training sessions for the new cocktail bar and restaurant, where unemployed participants learned how to become ‘welcoming hosts’ and deal with conflict management. Brassica was then offered ongoing council support for putting these jobless people to work, and lauded for its decision to pay staff the Living Wage.

The brasserie opened its doors and admitted customers to its lichen-walled interior in June. It was operated by a company called Tayone Food Limited, co-owned by Rami Sarraf and Dea McGill. When the company was forced to close in October, McGill complained of cash-flow problems. When Sarraf later reported her to the police for fraud, she accused him of foul play. Sarraf swiftly secured the rights to re-open the business in December under the unrelated name of ‘Brassica Ecosse’. Charmingly, he has promised to re-employ everyone who was formerly employed at Brassica. He might be commended for his brass-neck-erie (as Gill Bannister was quick to quip) as he still refuses to pay workers the wages they were owed when the company shut.

The unpaid wages amounted to £28,721, a sum which Sarraf could easily afford as one of the richest dentists in Scotland. One Dundonian sleuth has diligently deduced that he made half a million pounds in profits from the NHS in the last five years. That’s enough to supply the tooth faeries of Tayside for a generation (1250 new Taysiders born each year for twenty years, with 20 teeth each at a pound a piece, will cost the faeries exactly £500,000). But as a Roman satirist once said, the richer you become the more you love money. And, of course, the law is on his side.

Sarraf has suffered a little for his crimes. Unite Hospitality and Better Than Zero organised public and worker resistance through protests and petitions, reported in local TV news and press. Trust matters for a dentist, but brand damage can only go so far in a sector where more than half of businesses do not make it past the first year. Unions are supporting precarious workers to organise in hospitality, but this work is undermined by council schemes and back-door support designed to prop up employers and provide them with a pliant workforce. This is employability at work.

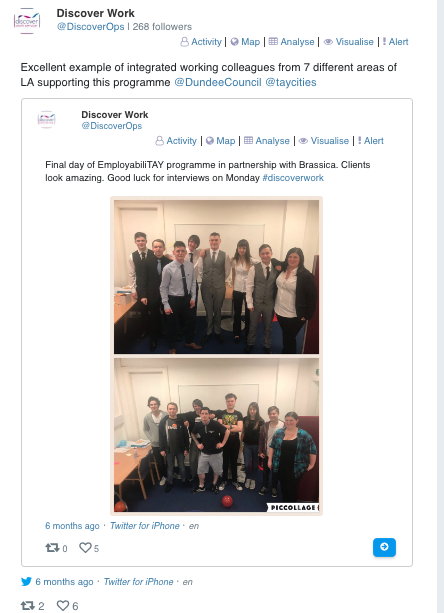

Dundee’s employability initiatives had their eyes on Brassica from the start. The local authority put a call out at the end of March calling on unemployed Taysiders to join the ‘HospitaliTAY programme being delivered in partnership with Brassica (a new high end Cocktail Bar and Restaurant)’. The course would provide participants with ‘industry recognised skills, employability skills and a guaranteed interview for a position with Brassica’. A few weeks later, at the end of April, the last day of the course involved the young ‘clients’ dressing in uniforms of hospitality service workers. One photograph, deliberately staged, captures their transformation from track-suited, jobless youths to trim, service-ready precarious workers. Discover Work shared the image as an ‘excellent example of integrated working [by] colleagues from 7 different areas of LA [Local Authority] supporting this programme’ [images below].

This inaugural HospitaliTAY programme ‘resulted in all 9 clients, some of whom had significant barriers to work, securing employment, 8 with Brassica’. Their recruitment was one of the Community Benefit which Brassica was obliged to make in return for the Waterfront premises. A similar ‘pre-recruitment’ programme was then developed with Sleeperz Hotel. Both courses consisted of ‘a 3 week programme of hospitality and employability training … catered to each employers [sic] requirements’. In August, Brassica was presented to the Scottish Parliament Economy, Jobs and Fair Work Committee as the outstanding success of Dundee’s employability programme.

Brassica was the first, sour fruit of a three-year policy reform. In 2015, Dundee City Council commissioned a consultancy firm called Rocket Science to design an employability strategy. The report by Richard Scothorne found evidence of a ‘jobs gap’ – there weren’t enough jobs – and a mismatch between skills required by employers and the skills held by unemployed workers. The solution would emerge by ‘ensuring a high quality match between the skills and aptitudes of those seeking work and the needs of employers’. Scothorne’s key recommendation was to increase the number of skilled workers, particularly machine operatives and skilled trades-people, but Dundee Council instead took it upon themselves to promote the hospitality industry through the Waterfront initiative, and to prioritise jobs in customer service.

Cultural infrastructure, such as the new Victoria and Albert Museum of Design, is supposed to create a new boom in the demand for hospitality and the so-called visitor economy. ‘Hotels, businesses and retailers are reaping the rewards’ of the £1 billion Dundee Waterfront project. Promises of 7,000 new jobs in areas including hospitality and tourism are the prospective future for Dundee’s next generation. Indeed, the city is aiming to be accredited as a World Host Destination, ‘the ‘must-have’ badge for customer service’, awarded to cities where a fraction of staff have been trained to give visitors ‘the attention that they deserve’ by ‘going the extra mile’. There are already over 1,500 people trained in hospitality and customer service, and Scothorne’s report found that there was not a significant skills shortage in the sector.

Dundee’s jobs strategy depends on coaxing customers into the city. With three quarters of them expected to come from ‘home turf’, Dundee’s civic bosses intend to defy – or deny – the signs of a shrinking Scottish economy. A strategy launched in 2015 aims to expand tourism by more than 20% by 2020. It’s an extraordinary experiment, and unemployed workers are the rats. But the city is optimistic. Lynne Short, the convener of the council’s development committee, said that growing visitor numbers are the ‘launch pad for the tourism offering’, with preparations well underway to provide people with ‘skills they’ll need to be able to meet the demand’.

Convener Short attended and promoted that first glass door meeting in April. She knows where the process started and where it ended for the unemployed young workers recruited by Brassica. Unfazed, the Dundee Jobs team is busy holding neighbourhood participation and engagement sessions every week, from Stobswell to Lochee, the Fintry to Broughty Ferry. Their Twitter feed features adverts for corporate courses, such as one hosted in September by Marks and Spencer offering ‘employment opportunities’ upon completion of four weeks of unpaid experience in ‘stock control, customer service and selling skills’. Meanwhile the Dundee office of Skills Development Scotland promotes the opportunity to be an ‘Apprentice Team Leader’ at KFC, and another employability charity, Changemakers, puts Costa baristas in its ‘jobs spotlight’, insisting ‘there’s more to the role’ than serving coffee. And although a website to ‘support people overcome barriers to moving into work’ is down, there is, squirreled away on the council website, a whole ‘employability map’.

Millions of pounds are invested by local authorities in employability schemes that focus on supporting private businesses. £25 million will fund ‘an Integrated Regional Employability and Skills Programme’ in Edinburgh and the South East, including an ‘integrated multi-agency regional employability and skills escalator’ to get people into entry-level employment. Edinburgh’s council-funded ‘Joined Up for Business’ service offers ‘bespoke recruitment’, ‘pre-recruitment opportunities’, and ‘work experience opportunities’, with companies incentivised to take on unpaid workers. It is hard to see it creating anything other than low-waged, precarious jobs, and a constant threat that the doors of your employer will shut as quickly as Brassica’s.

Brassica’s closure created an incendiary response. The stories from Unite members of angry and even violent reactions are hardly surprising. Meanwhile, the council has kept quiet about its ‘partnership’ with Brassica. It has made no suggestion that lessons have been learned for the employability scheme. Indeed, it has made no mention at all of its partnership with Brassica. When private companies and local authorities form hidden partnerships, what are the accountability processes for all the Sarrafs benefitting from such schemes? And to what extremes will it drive workers?

Featured image: demonstration at the closed doors of Brassica (7 November 2018) ©UniteHospitality. A new demonstration was called this morning, 13 December 2018.