In this article by Karthick RM offers us a Universalist reading of Frantz Fanon’s works including: The Wretched of the Earth. Arguing against identitarian politics fuelled by ressentiment, Fanon, offers us an account of post-colonial politics based in mutually critical engagement. Karthick argues that the crucial lesson we must take from Fanon is that every struggle for a better society is necessarily a struggle against oppression, but not every struggle against oppression is a struggle for a better society. And this is a lesson that the liberal-left has never learnt.

Why Fanon?

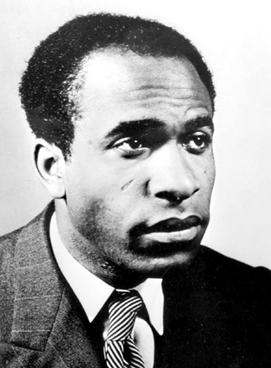

“It has never been more difficult to read Fanon than it is today,” remarked philosopher Achille Mbembe in a lecture at Colgate University in 2010. Frantz Fanon (1925-1961), an existentialist humanist from Martinique deeply influenced by Jean-Paul Sartre, worked as a psychiatrist in colonial Algeria and later joined the Algerian resistance against French colonialism. Popularly known for his The Wretched of the Earth, Fanon was the author of works that offer critiques of colonialism and racism, which are often prescribed as guidebooks by many radical identitarian movements even today. While the practice of reading Fanon has indeed never lost popularity, popular readings of Fanon need to be challenged if at all a radical Fanonism is to be retrieved. This article makes the case for a Universalist reading of Fanon, who called for a critical interrogation of all identities.

I first read Frantz Fanon in 2008. It was a turbulent time for me as a Tamil writer and activist. In a country not far from my home in South India, the Tamil resistance was making a desperate last stand against the no-holds-barred onslaught by the Sri Lankan government. Like me, several other Tamils in India and the diaspora in Western countries were on the streets, protesting against Sri Lanka and the states that supported its brutal military campaign.

In that period, The Wretched of the Earth was intellectual dynamite to me. “Violence can thus be understood to be the perfect mediation. The colonized man liberates himself in and through violence.” Reading his magnum opus in those times, his relatively simple (or so it appeared) first chapter on violence appealed more than the others, which dealt with quite complex issues. My Fanon was a Manichean, who stood against the violence of the oppressor, and legitimized the violence of the oppressed. Like several of his juvenile admirers across the Third World, I too read him as a prophet of violence. Violence was liberating, violence was cathartic, and violence was being. His exhortations for a relentless struggle seemed to be the only available option in a hopelessly unjust world.

Yet, I felt I was missing something crucial.

Contextualizing Fanon

The Fanon I came to discover upon closer reading is totally different from the character I read in parts while missing the whole. What was radical in Fanon, and what is most relevant for our times, is his attempts to unsettle both the identities of the oppressor and the oppressed towards a radical universality. Reading Fanon with discipline and sobriety, I could appreciate his theory as a consistent, rigorous attempt to understand the paradox of identity.

It is important to contextualize Fanon. Throughout his political life, Fanon was an outsider. A Black Martinician when in France, a French citizen in Africa, and one from a Christian background among Arab Muslims. Though he was fully committed to the Algerian anti-colonial struggle, he was never fully Algerian even in the eyes of his comrades. His grasp of pre-colonial Algerian history was hazy at best. Fanon’s writings clearly show that his understanding of Islam as a socio-political factor in Algeria was superficial and he viewed it only in instrumental terms vis-à-vis French colonialism. Anti-Black racism among Arabs, the Arab role in slavery, and Islamic patriarchy were all subjects he scooted over.

A foremost critic of Western imperialism, Fanon breathed his last breaths under the eyes of the CIA in an American hospital where he had come for treatment for leukaemia. He died in late 1961; Algeria would win formal freedom the next year. Independent Algeria was wracked by civil war between the government and Islamists, killing more people than French colonialism. One could say Fanon was lucky to have not witnessed this – his wife Josie Fanon committed suicide anguishing over the degeneration of an anti-colonial project into a savage and cynical struggle for power. He remains a marginal figure in the intellectual imagination of both France and Algeria. However, from the 1980s he has had an academic rebirth in the Anglo-Saxon world, mostly in the departments of postcolonial and race studies, where he is mostly read as a ‘Black’ thinker, an identitarian, a post colonialist, or as an advocate/analyst of anti-colonial violence. Yet, what is most important about Fanon, and what is his most unsettling aspect, is his revolutionary universalism, something both critics and admirers miss.

While Fanon has become a name that has been associated with violence, thanks largely to the interventions of influential critics like Hannah Arendt and supporters like the Black Power movement in the USA, Fanon himself had a guarded position as regards the potential of violence. It must be noted that his consideration of the emancipatory possibilities of violence occupies only one chapter in his entire works. On the other hand, the last chapter of The Wretched of the Earth is explicitly concerned with the pernicious psychological effects that random retaliatory violence can have on those participating in it. Fanon views violence in an instrumental manner, his approach to violence is more descriptive than prescriptive. Both Fanon’s liberal critics and his overenthusiastic supporters sadly, miss this nuance, Black and White alike. Philosophers like Sartre and Walter Benjamin have produced more intensive works on violence; it does indicate some prejudice that their names do not provoke a spontaneous association with violence while that of Fanon’s does.

“Concerning Violence”, a recent documentary by Goran Olsson, a Swedish filmmaker too reinforces the ‘angry Black man’ stereotype, albeit unwittingly. Olsson’s documentary takes select passages from The Wretched of the Earth to make a case against European colonialism. The Fanon we see here is an anti-European, who rejected all that Europe stood for. Yes, Fanon was genuinely angry towards the brutality of European colonialism, but he nevertheless believed that there was something worthy of redeeming in the European tradition.

Fanon writes in the conclusion of The Wretched of the Earth – and this is a passage that the documentary conveniently missed – “All the elements for a solution to the major problems of humanity existed at one time or another in European thought. But the Europeans did not act on the mission that was designated them.” These are not the words of a man who hated Europe; these are the words of a man who accused Europe of not living up to its own egalitarian values. This is a Fanon that neither the Right nor the Left recognize, and this is the Fanon desperately needed now. The “prophet of violence” who allegedly hated all things European is a person whom Fanon would have loathed. But I suppose this is the fate that befalls all great thinkers. Nietzsche remarked that a martyr’s disciples suffer more than the martyr. What he should have added is that a martyr’s principles suffer most in the hands of his disciples.

Fanon and Identitarian Violence

Fanon’s nuanced position on identitarian violence is worth considering, especially in the wake of the violent protests in Ferguson, Baltimore and other places in America over the police killings of Black people. Even as the mainstream establishment condemned it, the mainstream anti-establishment celebrated the violence as the beginning of a revolutionary uprising. The advocacy of indiscriminate violence to combat White racist power centres is nothing new. In the past, Black activists like Eldridge Cleaver advocated rape of White women as a form of resistance to White racism – though he later expressed regret for such ideas. Life came full circle when he eventually joined the Republican Party and became a Christian conservative. What does this say?

The reality is that the American system is more than capable of defending itself against such violent excesses by its minorities. If anything, it would prefer the pampering of such particularistic minority identity politics because the postmodern logic of global capitalism requires the proliferations of multiple minority identities. This impotent violence of particularistic identity politics, fuelled only by anti-White ressentiment, creates more boundaries and comes nowhere closer to destroying them, which alone would be the real radical act today. So the White racists who are phobic about the “brutal Blacks” and the multicultural left who, to overcome a misplaced sense of guilt, celebrate “Black resistance by any means necessary” are actually conforming to the logic of the same system.

Let us face it: America is the strongest military power in the world with the mightiest arsenal ever assembled in human history; it topples governments across the world at will; it has made counterinsurgency not just a matter of strategic practice but a way of thinking; and American scientific advancements affect not just every human soul on this planet, but also outer-space. If the White journalist sitting in a comfortable office on Wall Street condemning the violence of a racialized and poorest section of the country against such a power is morally wrong, the White liberal-left academic having a permanent position in a posh university enthusiastically condoning the violence of a racialized and poorest section of the country against such a power is downright stupid.

If America is to change for the better, it can happen only through a radical reform instituted by popular democratic forces from all sections of the population. Given the kind of might that America has, isolated acts of violence by identitarian groups against the state are unfruitful, if not suicidal. In this regard, it would be wiser to read Fanon with Martin Luther King than with Malcolm X. Both Fanon and King opposed the idea of separatism based on identity and instead made a case for an identity-based struggle to transcend itself to a struggle for a structural change of society as a whole. This of course is not a plea for liberal pacifism; neither Fanon nor MLK stood for that. But rather, we need to understand that the forms of protests that might have had some effect in the previous century will have none in this one. Fanonism is, among other things, a method to understand the dialectic of history.

Pragmatically speaking, the struggle for Black rights in America cannot be waged in isolation from other struggles. And it is here that Fanon’s universalism, and the need to go beyond one’s identity, is most relevant. In Black Skin, White Masks, challenging the practice of fixing rigid identities and closing off the possibility of universality, Fanon argued that those who adore the Black person are as sick as those who hate him. In Fanon’s (Lacanian) understanding, not only is the Black person emulating Whiteness pathological; the Black person searching for an authentic Blackness is equally so. Opposing determinism, he also says “I will not make myself the man of any past. I do not want to exalt the past at the expense of my present and of my future.” Unfortunately, the liberal-left seems to have abandoned universalism in favour of a very problematic form of particularistic, narcissistic and self-defeating identity politics.

Universalism and Solidarity

The reason why Fanon was suspicious of the particularistic Black identity politics of Negritude, popular in his time, was not only because its glorification of myriad pasts, but also because he believed that the simple binary mapping of Black and White obfuscated more than it revealed, often silencing other critical, more radical voices from the colonized. Isn’t this what is happening now in the debates around Islam? One can observe a monopolization of the discourse on Islam by both hard and soft Islamists, which is being actively or passively assisted by the Western multicultural liberal-left, at the cost of those within the so-called ‘Muslim world’ who are working towards radical political struggle and social reform within their own communities. How do we explain the near total silence among the mainstream left on the most important progressive struggle in the middle east, that of the Kurds? The reality is that the multiculturalist privileging of Muslim voices, both fundamentalist and ‘moderate’ Islamist, contributes to the further silencing of those who reject primordial religion based identity politics and seek alternatives in radical emancipatory political projects.

As a Tamil, I would really welcome an honest and merciless criticism of Tamil politics, the ideology behind it, and the identity it envisages, from those in the Western left even as I criticize Western values, or its absence. This type of mutually critical political engagement, not cultural niceties and a cheap patronizing tolerance, alone can guarantee that progressives from the world can create a universalist platform of struggle, while simultaneously undermining the narratives of racist bigots in the West that the “Others” are incapable of progress. If the Western liberal-left is unwilling to do this, the least it can do is avoid placating the bigots from “the Muslim world,” “the Hindu world” and other such deterministically fixed cultural-religious worlds, and give space to those political voices that believe in genuine emancipatory values.

This is a crucial Fanonian lesson: every struggle for a better society is necessarily a struggle against oppression, but not every struggle against oppression is a struggle for a better society. And this is a lesson that the liberal-left has never learnt. In their overzealous attempts to fight “White Imperialist Capitalist Patriarchy,” the Left, or the loudest voices among them, has become apologists for the most horrid forms of fundamentalisms from the Third World. In their illusions that they are combating the West, they legitimize the worst from the Rest.

In these times, where obsessing over particularities of race, ethnicity and religion has reached fetishist proportions among both the Right and the Left, Fanon’s universalism and his call to challenge the limitations of all fixed identities cannot be more pertinent. As he said in the conclusion of Black Skin, White Masks “It is through the effort to recapture the self and to scrutinize the self, it is through the lasting tension of their freedom that men will be able to create the ideal conditions of existence for a human world.”