“Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will” – Frederick Douglass

“I feel that if we don’t take seriously the ways in which racism is embedded in structures of institutions, if we assume that there must be an identifiable racist who is the perpetrator, then we won’t ever succeed in eradicating racism” – Angela Davis

“If potentiality, then, can be said to be the site of the human, rather than the nonhuman, fixedness; more precisely if it is the “place” of the subjectivity, the condition of being/becoming subject, then its mission is to unfold through “words, words, words”, yes, but “words, words, words” as they lead us out to the re-presentation where the subject commences its journey in the looking glass of the symbolic.” – Hortense J. Spillers

In the wake of the murder of George Floyd on the 25th of May 2020 in the city of Minneapolis, a global anti-racist rupture in the fabric of racial capitalism has occurred. Floyd was murdered by police officer Derek Chauvin, who knelt on Floyd’s neck for almost nine minutes. Floyd after calling out “I can’t breathe!” was essentially choked to death on an open street. The act by Chauvin and the lack of action by the other police officers was captured through the cell phone cameras of bystanders. Despite this event happening under the conditions of the dispersion of the visual field and in an era of technological surveillance, the cops did what cops do.

The behaviour of these officers cannot be seen outside of a racial logic of ‘White supremacy’ and entitlement to take another person’s life, a sense of owning the fate of the Black body. ‘Violence [often] occurs’, Butler (2020) argues ‘in the series of legal refusals and failures to recognize it as such: no report means no crime, no punishment, and no reparation.’ The dispersion of the visual field, therefore, serves to make violence (un)disputable, making visible how actual life depends on its virtual circulation.

The fate of the Black body is one which has been and continues to be systematically subjected to racism, exploitation, othering, stigmatization and continued erasure. “Black Lives Matter”, therefore, stands as a movement, a political mobilisation, which gives a simple message: ‘Black sociality’ (Moten 2003) matters, whether it is black thought, life, art, or labour – whatever form or shape of Blackness, it is to be counted, it is to be made visible in our social order, in our language, in our knowledge, in our understanding of Being.

The name “Black Lives Matter” (extending beyond its particular origins) asserts itself and circulates in discourse through forms of speech and action, giving voice to what is not included, making visible the presence of an absence (Spillers 1996). In asserting itself in discourse, the claim “Black Lives Matter” ruptures the silence – the silence which is in and of itself violent, as it works to conceal, censor, and cover-over the violence of the racial orders which structure human sociality. The absence is one of Blackness, as the structures of racism are figured around and premised upon the false ideology of “Whiteness”, positing a binary logic of that which is “White” and that which is not. Within the racial dualism of the metaphysics of “Whiteness” there are no grey zones.

The logic of racialisation and categorisation are, unfortunately but not accidentally, fundamental to the world we live in. The persistence of racialised logics of social organisation are premised upon an idea of supremacy and forms of articulation, which establish particular subject-positions, dividing people and the world up in categories of “White” as the proper, and “non-white”. This falseness is further evident insofar as racism is not premised upon any biological determinism as commonly thought, but on a system of power/knowledge (Hall 2017), which places Black bodies in ungrievable and precarious positions. This is not a denial of the material culture and experience of Blackness, but a challenge to the racialised identities which are a contingent and the work of human fabrication in the service of “Man” (Wynter 2003).

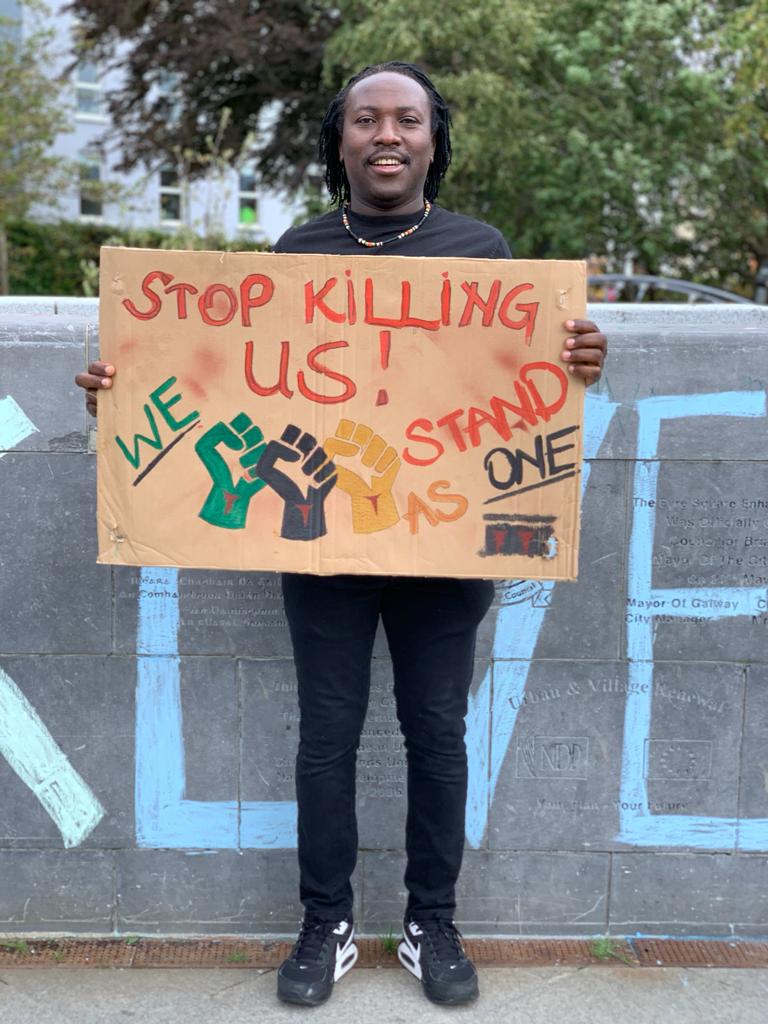

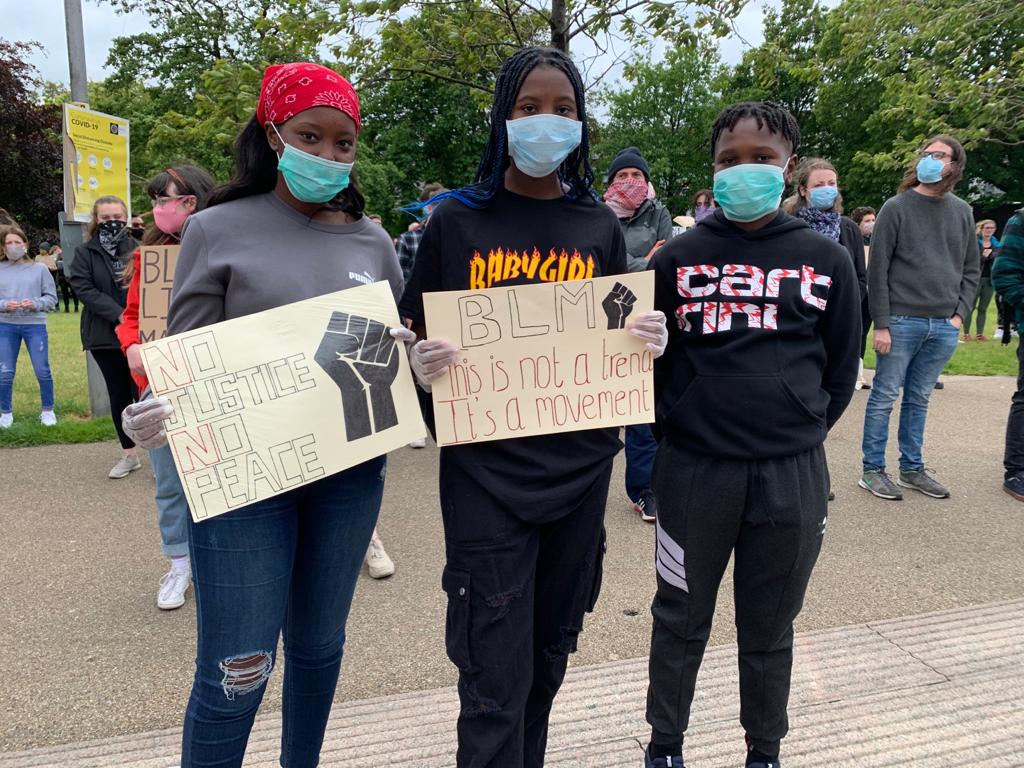

Protests are now happening in many countries around the world, in spite of the constraints everyone is facing with the Covid-19 pandemic. People have begun to gather, collectively and bodily on the streets of cities across the world in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement in the USA and in anger and grief at the blatant acts of police brutality and violence, towards George Floyd and those who have come out to protest his murder. Protest movements in many countries, and some other movements are using and borrowing the claim of “Black Lives Matter” as it circulates globally, and at a remove from its “original” citation. It’s re-articulation has been put to work to shed light upon forms of systemic racism experienced by other racialised identities, such an oppressed minorities, refugees, stateless peoples, and migrants.

But to what extent can we borrow the name “Black Lives Matter” and in what ways are we taking away from the material reality of Black peoples suffering when we borrow their claim? Is this expression of solidarity undermined as the phrase “Black Lives Matter” is extended, stretched, and used to reframe other struggles against racism? As we have seen in recent days, this claim that “Black Lives Matter” has been taken up by some members of both the Kurdish and Palestinian movements, as well as by anti-racist campaigners in Denmark, Ireland, France, and the UK (to name but a few) in (re)naming their respective struggles for justice as being in a relation of equivalence to the Black Lives Matter movement and its struggles against police brutality. To be clear for those who are at this point inclined to mis-read my argument, I do not raise this issue as a criticism of those movements, but to call upon ourselves to critically examine what it is we do.

From a psychoanalytic perspective, race might just be that which has an unchanged face, which remains the same despite the ‘weather, geography, culture and language’, so that it produces the same phantasms and desires (Spiller 1996). The logic(s) of race and racialisation, however, works differently across contexts. The anti-racist movement is now global, transnational and extends beyond Black bodies, to other racialised categories of people. But histories and cultures of racism are not the same. As Spillers has argued, in treating the phantasms of race as transcendental and global phenomena, we flatten out what is meant by Blackness, only ‘to run the risk of reinforcing the very myth that we would subvert’ (1996).

It is in this very political tension that we must pause to ask, where are we left in thinking and enacting forms of solidarity which do not reaffirm essentialism, nor erase the very movements which name the wrong that we stand in opposition to? This question becomes all the more urgent as we witness and draw upon the claim of “Black Lives Matter” as it emerges as potentially a powerful transcultural, transhistorical, transnational slogan, aimed at the critique of, and the-will-towards putting an end to racism, as a global issue.

In drawing upon the claim “Black Lives Matter” the difficult task becomes one of how one extends solidarity, but does not reintroduce competing narratives of struggle. To say that “All Lives Matter” or that “Blackness” extends beyond the context of the USA, risks the slogan being commodified and captured by those who want to use it to their own ends. That is not to say, that the claim “Black Lives Matter” cannot be used by other racialised identities. The reality is that it names quite clearly an issue of racism, which is systemic. What’s more in affirming that “Black Lives Matter” we approach the everyday philosophical and ethical problem that not all lives are counted as equal under the present conditions of racism. As such, the particular claim of “Black Lives Matter” has the capacity to extend beyond its immediate context to draw attention to other forms of racism.

This name and claim encourages us to think once again the forms of connectional power and domination which proceed under the logic of race, and in so doing ‘has renewed our appreciation of the necessity of coalitions and solidarity against oppression’ (Brizuela and Esmeir 2020). As we know, White Supremacy in fact does not discriminate between that which it deems non-White. What we see here is a tension which needs to be balanced as we engage in politics, extending solidarity and broadening the frame of visible racism. At stake is not an either or, but a hegemonic politics of equivalence without homogeneity, solidarity in difference, difference without separation (Da Silva 2016). It is this very tension and its potential risks which we need to remain vigilant towards and sensitive to. Racism is both specific and global.

But in what scene does politics now emerge?

It has been impressive to see so many people protesting, whether they do so on the streets, online through posts on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram and all the other social media platforms. The character of, and possibilities for protest and political forms of speech and action, we can suggest, have transformed with our increased social media use. The spaces in which we engage in politics have, over the past ten years, changed and pluralised dramatically, and the Covid-19 pandemic only serves to accelerate this further. The public space of the plaza or city streets are no longer a place where we can easily meet. Regulated by emergency laws in the name of the real and immediate danger of Covid-19 the streets now pose a different danger than that of racist violence. As such, Covid-19 and developments in the world of social media throw into question our conventional understanding of the politics of the streets as gathering on mass, in close proximity, placing our bodies on the line.

Can we do politics on the streets during Covid-19, is a question posed by many, and yet clearly rejected by others that still go out onto the street. The virus undeniably exposes our innate vulnerability, but vulnerability must not be equated with passivity here, as vulnerability and resistance work together as resistance can be ‘opened by vulnerability’ (Butler 2016).

To organise with masks on, abiding by social distancing rules during Covid-19 is a powerful political statement. To protest during Covid-19 when there are legal prohibitions against gathering, we might suggest, leaning once more on Butler’s words, functions in two ways: ‘the ban was shown, incorporated, enacted bodily—the ban became a script—but the ban was also opposed, demonstrated against.’ Activists engage in forms of care, distributing face masks, providing hand sanitizer and practicing forms of spatial distancing. The very forms of regulation by the state become an opportunity for subversion and a space which opens on to democratic care.

With the masks on, our speaking is confined, nobody can see our faces fully, our voices are muffled, as we grasp for air, a certain degree of absence is made present. Speech is tied behind the veiling of a body that willingly throws itself in presupposed danger by putting itself on the line, a line which is not only fragile due to Covid-19 and the illegality of gatherings, but in some places made dangerous by more authoritarian tendencies which seek to shut down people’s demands for equality.

To be on the street in this instance is to make a bio-political claim of equality and to demand that Blackness be made part of the count. To do street politics during Covid-19 is for “Black Lives Matter” or anyone who is re-iterating that slogan, is clearly to demonstrate our shared vulnerability and to demonstrate with it: ‘what happens is not the miraculous or heroic transformation of vulnerability into strength, but the articulation of a demand that only a supported life can persist as a life’ (Butler 2020).

“Black Lives Matter”, as a claim, takes on a new and interesting significance in light of Covid-19. It is not taking from the urgency and concerns for public health during the outbreak of Covid-19, but stands as a constant reminder of a greater human disease, which is even more infectious and kills a larger number of people on a daily basis – think only of the Black lives lost and destroyed in the illegal extraction of the resources which lubricate the logistical workings of capitalism. With Covid-19 many people have rediscovered a global concern for “humanity”, but maybe we ought to also ask to what extent our renewed humanism is also premised upon forms of individuated self-concern, and the will to be ‘a singular being’.

“I can’t breathe!”

Covid-19, Achille Mbembe (2020) reminds us, makes it difficult to breathe. Mbembe suggests we need to begin to look at breathing beyond the biological. The reason people are mobilising and going out onto the street is due to the lack of breath – not only a breath that is physically constrained but an everyday racism which confines humans, their values and creates schemas for how bodies should be, particularly Black bodies. To overcome and cancel this given, we have to engage in a sort of self-formation authored elsewhere, by a different set of pens, a rewriting of our own subject-position within the material and symbolic orders of racial capitalism and power. We also have to start seeing ourselves beyond the threshold of the fleshed, the material, and to work upon our own psychic and phantasmatic investments within the orders of race and inequality.

The already-answered of race (that there is no basis for race), is not only our blindside to its existence in the structures we form part of, but also through the ways we have internalised its logic. But what does it mean if we were to own up to the fact that we might all be part of a racial structure and unintentionally reiterate it through our speech and actions? That we uphold its power by obeying a number of authorities, structures, positions, institutions, and forms of life? All of which function to perpetuate the very same logic we are now globally condemning – racism. One can intend to do otherwise, but most of us reproduce without awareness – awareness can only happen through words, words, words (Spillers 1996).

***

Hasret Çetinkaya is a post-colonial feminist working in the field of critical social theory & human rights. She is doctoral candidate at the Irish Centre for Human Rights, NUI Galway.

A note of thanks to Su-ming Khoo and Kate Kenny for their inspiration and insights on the texts of Butler and Spillers which we have been reading together.

Should you wish to support the struggle against racism, for the cessation of the Direct Provision system here in Ireland contact and follow the work of:

Black Pride Ireland – @BlackPrideIre on Twitter

MASI – the Movement of Asylum Seekers in Ireland https://www.masi.ie/

MERJ – Migrants and Ethnic-minorities for Reproductive Justice http://merjireland.org/

MRCI – Migrant Rights Centre Ireland https://www.mrci.ie/

NASC – The migrant and Refugee Rights Centre https://nascireland.org/

GARN – Galway Anti-Racist Network https://www.alltribeswelcome.com/

Irish Refugee Council – https://www.irishrefugeecouncil.ie

References

Brizuela, N. and S. Esmeir. 2020. ‘On Anti-Blackness in the United States’, Newsletter of the International Consortium of Critical Theory Programs, June 5.

Butler, J. 2016. ‘Rethinking Vulnerability and Resistance’ in J. Butler, Z. Gambetti and L. Sabsay (eds.) Vulnerability in Resistance. Durham: Duke University Press.

Butler, J. 2020. The Force of Non-Violence. London: Verso.

Da Silva, D.F. 2016. ‘On Difference without Separability’ for the catalogue of the 32a São Paulo Art Biennial, “Incerteza viva” (Living Uncertainty).

Hall, S. 2017. The Fateful Triangle. Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press.

Mbembe, A. 2020. ‘The Universal Right to Breathe’, in Critical Inquiry. Available online at: https://critinq.wordpress.com/2020/04/13/the-universal-right-to-breathe/

Moten, F. 2003. In the Break. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Spillers, H.J. 1996. ‘“All the Things You Could Be by Now If Sigmund Freud’s Wife Was Your Mother”: Psychoanalysis and Race’, Critical Inquiry 22 (Summer): 710-734.

Wynter, S. 2003. ‘Unsettling the Coloniality of Being/Power/Truth/Freedom Towards the Human, After Man, Its Overrepresentation – An Argument’, CR: The New Centennial Review 3(3): 257-337