In this short piece Liam Farrell argues that recent acts of naming the Irish Republic, either as a ‘Vulture Republic’, or as a ‘Republic of Opportunity’, stand as linguistic attempts to resolve the ongoing housing crisis in Ireland, which has its roots in the financial crash of 2008. Moreover, in such names we find avenues for populist action towards a more egalitarian and just society.

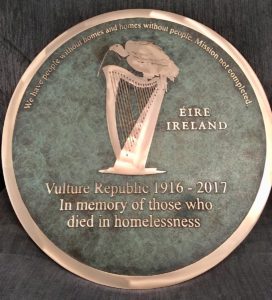

Apollo House, soon to be demolished, and formerly the residence of the Department of Social Protection, before being taken into the possession of NAMA, the National Assets Management Agency, was occupied in the winter of 2016 by homeless citizens and local activists under the name ‘Home Sweet Home’, in order to provide emergency accommodation for those exposed to the worst housing crisis and homelessness situation that Dublin had experienced in a generations living memory, with 142 persons sleeping rough in Dublin on 22nd November 2016 and approximately 2,922 adults in emergency accommodation that same winter. By the winter of 2017 and the appearance of the ‘Vulture Republic’ plaque, the homeless people count was 184 persons on Dublin’s streets.

The mobilization of the sign of the vulture is significant in this instance, not only in invoking the recent deaths of homeless men, persons deemed surplus to the uneven allocation of both grievability and vulnerability within the ideological frames of those in government and their corpses offered up to the vultures, but, further, in recourse to the proliferation of discourses of ‘vulture capitalism’ and the broader context of the sale of NAMA assets in the preceding two years.

The role of ‘vulture capitalists’ in the ecology of housing supply in the Irish state has now been well charted; with a plethora of predominantly US based funds (including the Goldman Sachs affiliated operations Beltany and Ennis, as well as Cerberus, Lone Star and Blackstone), purchasing distressed properties and loans from banks and mortgage companies eager to see such accounts off their books. Widespread home evictions have ensued. The government’s position on the proliferation of ‘vulture’ activity in the midst of a severe housing crisis is neatly captured in the words of the then Minister for Finance: Michael Noonan TD (FG). When questioned by Ruth Coppinger TD (Solidarity – People Before Profit) about the purchase of ‘distressed loans’ by international ‘vulture funds’, at the Oireachtas Committee for Housing and Homelessness on 30 May 2016 the Fine Gael (Irish Conservative Christian Democratic Party) minister replied with an air of indifference: “You criticize me for not intervening with vulture funds. Well, it was a compliment when they were so dubbed in America because vultures, you know, carry out a very good service in the ecology. They clean up dead animals that are littered across the landscape.”

The names given to the Irish State by its political leaders – usually in the form of campaign slogans as a means of giving metaphoric representation to the ideals for which they stand – are a good marker of the prevailing ideology of that regimes vision. By the time the commemorative plaque appeared on the now no-longer occupied Apollo House, the leadership of the governing party, which presided over the political origins of the ongoing housing crisis, has been replaced. Upon launching his campaign for leader of the party, and ipso facto Taoiseach, Leo Varadkar TD, set forth a vision for the nation as a ‘Republic of Opportunity’. The content of such a name, lies in a promise of tax cuts for middle class voters, and government for those ‘who get up early in the morning’. In such a claim, and the attending policy document by Fine Gael that shares the name: The Republic of Opportunity, we see a deepening of the neoliberal ideological project under the Varadkar regime, which is ostensibly pro-business, and coupled with an incompetence and indifference towards confronting the political conditions which have led to housing and homelessness crisis, which radically questions the name of a ‘Republic’.

What I want to suggest here is a rather elementary observation, which I think has political potentialities to explore. There is, I argue, no point of rupture between the two names of ‘Vulture Republic’ and the ‘Republic of Opportunity’. The opportunity that it names is but an element of that opportunity for ‘Vultures’ to run free. This is the opportunity of minimally restrained capitalism to profit upon the lives of citizens and small business owners.

Nonetheless there is something more to be gleaned from such names. They both give meaning, which is deeply political, to a shared concern: that is the ideal of the Republic. Here we find in such naming two worlds within one, an ironic characterization of an ideal with the name ‘Vulture,’ suggesting immediately its inverse as their goal, and an honestly held vision for the future, which is blind to the exclusions it brings forth.

Politics is ultimately the struggle over the future through the names and visions we give to it, and this struggle implies that we find ourselves in a situation in which there are two worlds within one. What is at stake then is a struggle between two different understandings of the world, as it is, and how it should be, which collide around a single, common, and yet contested word: ‘the Republic’. If politics is to be emancipatory it must be oriented around making manifest the one universal ideal of democratic life: the republican principle of equality.

Equality in this instance is not a concept of sameness, but a starting point, a primordial condition which is betrayed by society, private property and inegalitarian regimes of power, yet, nonetheless, has the redemptive presence to throw into question each and every injustice which society produces. Politics as such is a struggle in the name of equality, not in order for the poor to oppose the rich, but to make the poor visible to the rich, as speaking beings, and as citizens. Emancipation(s) then is always plural and never complete.

In naming the present conjuncture as that of a ‘Vulture Republic’, and in coming together to take a space to shelter, erect showers, and cook food for themselves and other members of the community rendered disposable by the state, such homeless activists and fellow travellers staged democratic politics in what is a highly effective form. Through such actions, and such a staging of a political wrong, they fundamentally altered the commonsense understanding of space and property, as well as providing an exemplary model for how emancipatory politics must ultimately be egalitarian, populist (i.e., done in the name of ‘the people’), and antagonistic.

[…] where several houses are boarded up and vacant. ‘People without homes; homes without people’. There are solutions. As Liam Farrell maintains in his February article on homelessness and vulture […]