Who are the elite capital-owning class, and how do they think about precarious work? Cailean Gallagher offers a case-study of the tycoon behind the Edinburgh Hogmanay Underbelly scandal.

This story starts at the door of a large, timber-framed mock-Tudor house near the sleepy English town of Saffron Walden, where a lawyer and capitalist called Thomas Page lives with his wife Isabelle, their three boys, and their brown Burmese cat Maddie. Tom is a trustee of Littlebury Village Hall, where Isabelle recently organised the Burns ceilidh – complete with glass of fizz and ‘Scottish supper’ (whatever that is), and music by the Cambridge University Ceilidh Band. The Pages’ garish unionism, subtle bunting and annual holidays to the US make them the kind of well-reared British breed that suits a village such as Littlebury.

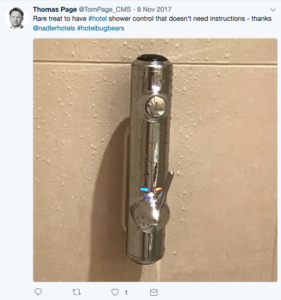

But Tom Page’s respectable prosperity conceals an ugly underbelly. Tom has two roles in life. Most prominently he is global head of hotels and leisure for the law firm CMS, making him a prominent player in the field of hotel management and investment. For instance, he recently acted for the multi-millionaire Bhatia tycoons when they acquired the DoubleTree hotel near Tower Hill in London for £300 million. And he is happy to share the occasional intimate moment from his hotel-centric life: a tender tweet shows a close-up of a shower control unit and thanks Nadler Hotels for the ‘rare treat’ of a fully functional shower.

In his other role Tom is Associate Director of Underbelly, a hospitality and entertainment company that operates in London, Edinburgh and Hong Kong. The company shares are owned by two ‘persons’: Tom is one, and the other is a company called By Popular Demand Promotions Limited, which is owned by Underbelly’s founders, Ed Baltram and Charlie Wood. Despite the founders’ claim ‘never to have had a business plan’, the company is gorging on the Edinburgh entertainment scene, and has grown into one of the ‘Big Four’ Edinburgh Fringe oligopolies.

Old Etonians

Apart from having a sizeable stake in its activity, Tom’s role in Underbelly is opaque. His function in the rise of the company is never mentioned in the interviews that the Old Etonians Baltram and Wood like to conduct for the Scottish press. But for a hint of the role Tom plays, we may look to his background. Page also attended Eton, and, as we learn from the edition of the Eton Chronicle that was issued on 17th October 1991, Charlie Wood and Tom Page were two of four ‘O.E.s’ (Old Etonians) responsible for ‘a breakthrough in the recent history of Eton Drama… by financing, organizing and producing two plays in the Edinburgh Festival Fringe.’ In an earlier issue from the 4th of June, 1991, Tom Page is credited with being the one who was ‘lucky enough (or skilled enough!) to find a venue’, and his commercial wit left the ‘boy-run production’ free to deal with such trivial questions as ‘Where do we get the money? Where do we get the props? Where do we sleep (on the street)? Where are the girls?’

It was a classic case of English private-school kids coming to Scotland for the Festival. A quarter-century later and Underbelly holds a £5 million, three-year public contract to run the official Edinburgh Christmas and Hogmanay parties. It is a contract that comes with significant prestige and public sector backing. And back in the autumn, these O.E.s decided to use their contract to test the limits of legal exploitation by attempting to recruit a team of 150 workers to work for up to 12 hours, unpaid, on New Years Eve, and a similar number to work the night before on the 30th December Torchlight Procession. These workers, dubbed Ambassadors (and described in a previous NP article) were to be ‘the welcoming faces’ to ‘assist those attending the party with information; from details of the performers on the music stages to the nearest exit points’. In return, they were to have some expenses paid and would receive a certificate for their labour. It amounted to certified pliancy.

The plan drew anger and protest from campaigners, including Better than Zero, which took steps to undermine the recruitment process, ultimately reducing the number of volunteers to just 19. Underbelly initially had the support of Volunteer Edinburgh, whose head telephoned Wood bemoaning that volunteering was being dragged through the mud by campaigns like Better than Zero. Meanwhile, Volunteer Scotland’s CEO, George Thompson, contacted Better than Zero, after discussions with Underbelly, to propose mediating between the campaign and Underbelly, and using a Volunteering Charter signed by the Scottish Trades Union Congress as the guidelines for ‘improving’ the unpaid roles. Instead of ‘getting to yes’ and approving some modifications to the contract, Volunteer Scotland instead was persuaded to withdraw its support from Underbelly. Some days later, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon was making thinly veiled threats about Underbelly’s plans. But for all that, Underbelly continued to insist that running Edinburgh’s Hogmanay was “not about the commercial return” – and even claimed to be contributing to the social good.

A stacked deck?

The broader point here is that by official standards, they were doing everything right. Part of the tendering form required the bidder to state how its delivery would result in some kind of community benefit. In the ‘summary of the expected community benefit’ the form stated that ‘the Council will work in partnership with the Contractor on supporting the Edinburgh Guarantee’s vision of increasing the number and range of employment opportunities or other support available for the city’s young people’. The Edinburgh Guarantee is a council-funded project ‘to increase the number of jobs, education and training opportunities for young people’ – holding events to help businesses understand ‘the talent that Scotland’s young people bring to business and the impact they have on sustainability and profitability’. The Ambassadors would get exactly the kind of ‘work experience’ that builds obedience, stamina, employability – and profitability for the employers. Here, unpaid work is not simply a quotidian fact of life accepted by interns and young people seeking work-experience, but was instead an explicitly publicly funded public good, all in the name of skills-development and employability.

Contrast this kind of opportunity with the skills-development afforded to young people in Littlebury, where our antihero, Thomas Page, resides. In 2016 the local cinema ran a film competition for youngsters. The winning film was called ‘A Walk in the Park’. It shows an animated lad who takes a dog for a walk but doesn’t have the patience to throw the stick for it over and over. So the lad gets a machine that will do the work for him – the Stick-Thrower 2000. This machine hurls the stick and the dog follows it across a country estate, past 10 Downing Street, into outer space, before returning to the town of Saffron Waldon, where the dog fetches it and returns it to the boy. The creator of this winning film was Tom’s son. The moral, presumably, is that if you are in a position to acquire a device that works for nothing then your life will be a “Walk in the Park”. For the young Page progeny, raised in the class of respectable lawyer-capitalists whose lifestyles are maintained by low-paid and unpaid hospitality workers, it is no doubt a familiar moral.

Making the most of it! Testing the limits of the law

For another angle into this mentality, it is worth consulting CMS’s journal ‘Hospitality Matters’, which Page often edits. In a recent issue his Edinburgh-based colleague Finlay McKay suggested that offsetting the increase in the minimum wage might require ‘a reduction in other employee benefits’ or ‘change[d] shift patterns’, and that substantial changes may impact ‘employee relations, which will need to be carefully managed.’ Lest his readers were complacent, he warned them that: ‘Although many areas of the hospitality sector are not unionised, this does not prevent unions speaking to the press to condemn business decisions and generate negative publicity. The furore over the way certain restaurant chains charge staff to process their tips was widely condemned by the union Unite, and ultimately led to the consultation on the payment of tips.’

It comes as no surprise when industry journals suggest shuffling shifts and cutting worker benefits. It is the practice of these lawyers to facilitate lawful reductions in terms, conditions and wages, and test the limits of law in reducing employment costs to as close to zero as possible. And just as they are more riled by union resistance than any small-scale gangster, so unions need not just to expose the unlawful malpractice of the worst offenders – the crooks, and the cranks, who run dodgy dealing bars and clubs in every town – but to illuminate profane, pervasive and permitted exploitation. Every capitalist family has an underbelly like Tom’s – hidden from the light, but supported by the law. Because it is legal, and indeed encouraged by legitimate political bodies, unions will need to ground their claims beyond the established rules of the labour market, act on the pretense that normal workplace exploitation can be endured no longer, and prepare for open conflict between owners and workers that will otherwise keep being mediated away.

Cailean Gallagher lives in Edinburgh, works in the trade union movement, and is researching Jacobite political thought. @apudscotos