Last May, ten British cinemas previewed Baywatch, Paramount Studios’ newest super production. In spite of the movie’s $70,000,000 budget, few blockbuster fans turned up: most cinema rooms were more than half empty. Baywatch made only $177,369,571 in profit; quite a failure by today’s standards. After a series of Hollywood blockbuster fiascos (Pirates of Caribbean 5, Valerian, and The Mommy), it is as if the American industry is replaying the 1960s.

The old-fashioned Marxist analysis, caricatural and caricatured, arguing that all artistic production is shaped by its conditions of production has fallen into disuse. However, as reductionist as this approach is, it can still be applied to the cinematographic industry. In some measure it can explain the reason behind the contrasting quality differences in movie production over time. American cinema between the 1970s and the 1990s exemplifies this theory.

At the end of the 1960s, the movie industry was bloodless. In 1950, cinemas welcomed more than 20 million people; fewer than before the war. But by 1975, only 4,6 million people went to the movies. During the 50s and 60s, Hollywood seemed content with its comfortable benefits and did not try to modernise its productions. While in Europe the movie industry witnessed its first golden age (Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal in 1957, Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima mon amour in 1959, Michelangelo Antonioni’s L’avventura in 1960), American studios released standardised feel-good musicals such as Rober Wise’s The Sound of Music (1965).

The New Hollywood era

Consequently, by the beginning of the 1970s, the major Hollywood studios (Paramount, Universal, MGM, Fox) were on the verge of bankruptcy. To prevent them from collapsing, the industry needed new ways of attracting its lost audience. From this flourished a new generation of directors and for the first time they emerged mainly from university film schools (UCLA being the most notable example) and were inspired by the European industry– who enjoyed a freedom their predecessors never had. This young generation, in contrast to the antiquated studio directors, understood the American civil rights movement, the opposition to the Vietnam war, and the ongoing consolidation of the New Left. Major studios had no other choice but to give some power to these young directors who seemed to know how to meet public demands.

When directors refused the industry’s traditional standards in the 1950s, they were marginalised and compelled to shoot their films in poor working conditions: for example, the movie Shadows (1959), directed by John Cassavetes, was made under a very tight budget and thus could only cast unprofessional actors. However, the 1970s’ young generation accrued an unprecedented room for manoeuvre. For the first time, directors had ‘the final cut’ (meaning that the entire filmmaking procedure was left to the director’s discretion, as studio managers lost the chief influencing power they used to enjoy).

The release of Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde, a movie especially shocking for its use of violence, marked 1967 as the beginning of the New Hollywood era. Since then, a series of creative and challenging films erupted, mixing violence and American social issues, with the idea of personal alienation characteristic of European cinema.

These movies distributed by the major studios reached a large audience. Great filmmakers also emerged. In his famous The Last Picture Show (1971), Peter Bogdanovich plotted the tediousness of American rural life against the backdrop of the Korean War. It was one of the most pessimistic films of the decade. Martin Scorsese encountered success during this period too, with Mean Streets in 1973 (first stage of a collaboration with Robert De Niro) and then with Taxi Driver in 1976, as it was one of the first movies addressing the Vietnam War. The latter became a symbol of the New Hollywood era for its violence and darkness. The Vietnam War became a source of increasing preoccupation for contemporary directors. Francis Ford Coppola tackled the subject in Apocalypse Now (1979) -Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival- and Michael Cimino raised the question of the psychological traumas caused by the war in his three hour long movie The Deer Hunter (1978). Illustrative of the greater degree of freedom amassed by these new directors, is the carte blanche Cimino received from the studios following his success. Finally, Heaven’s Gate‘s (1980) disastrous commercial failure, which led to the bankruptcy of its producers, United Artists, was the fiasco which symbolised the end of the New Hollywood era.

Back to the easy formulas

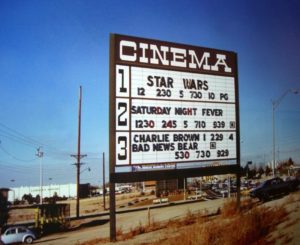

This cultural effervescence did not last more than a decade. The first blockbusters (Jaws, Star Wars) were a big commercial success and bailed out the studios thanks to their more consensual and less political themes compared to their early 70s counterparts. With surging rates of profit, the Hollywood industry slowly regained its power. Hence, there was a return to standardisation: Star Wars became a trilogy. There began the era of sequels, providing a system of ‘easy money’ that disadvantaged innovative and original films. The 1980s was a flourishing decade in terms of monetary revenues for Hollywood, but not so much in artistic terms when compared to the previous decade. ‘Underground’ movies (like Stranger than Paradise from Jim Jarmush or Blood Simple directed by the Cohen brothers) were produced and promoted by independent studios from New York, but did not reach audiences as vast as Scorsese’s pictures did ten years before.

Nonetheless, this artistic decline cannot be explained solely by the increase in studios’ revenues. Surely, the new political atmosphere characterising the USA at the beginning of the 80s —the advent of Reaganism and the emergence of ‘Yuppies’— also had an impact. In any case, it is hard to explain this reality without referring to the conditions of production which have been mentioned. To be clear, the point here is not to flat out dismiss the idea of the ‘blockbuster’ itself. The financial leverage of major studios allows them to hire a considerable number of excellent producers and are thus able to promote artistic creativity. For example, Guardians of the Galaxy (2014) directed by James Gunn brought a breath of fresh air to the super-heroes universe. The new Spiderman movie did the same by being ‘a joyful blockbuster in its dialogues, its secondary characters, as well a as in its thrilling action scenes’ (Mury, 2017). In spite of a panting system valorising standardisation and repeating the same mistakes all over again, Hollywood still has room for innovative cineasts in its studios.

To go further:

- BISKIND Peter, Le Nouvel Hollywood : Coppola, Lucas, Scorcese, Spielberg… La révolution d’une génération, Le Cherche midi, coll. « Documents », 2002.

- BERTHOMIEU Pierre, Hollywood moderne – le temps des voyants, Rouge profond, 2011.

- MURY Cécile, ‘Spider-man: Homecoming’: un blockbuster vif et réjouissant, Cinéma, July 2017, http://www.telerama.fr/cinema/spider-man-homecoming-un-blockbuster-vif-et-rejouissant,160727.php

Translation of the article of Pierre-Louis Poyau, Bis repetita à Hollywood ou comment ne pas apprendre de ses erreurs, published in Le Vent se Lève. Translated by Amélie Gaillat.

Photo credit: ©Patrick Blaise. Licence: CC0 Creative Commons.

Mr. Saulnier”s suggestion in the last paragraph seems so reasonable and long-term beneficial to all parties that it is assured of never, ever happening. Netflix execs doubtless prefer escalating the pissing contest instead, because they are not merely indifferent to the wishes of traditional cinephiles, but outright contemptuous of them. The Scorsese experience may tell the tale. If that movie gets flushed away at the mercy of algorithms, then we”ve had it.