Per Rolandsson discusses why Scandinavian culture has become so popular among the liberal middle-classes. Is it fascism, racism, or escapism?

Escaping the reality of today’s political conditions through culture has become a bother. The gloomy cultural theorists of the 50’s through to the 70’s had such an easy job describing how ordinary, hard-working people, could shut off their worries by turning on one of the three TV channels, going to the cinema, or switching on the radio to listen to the BBC. Your cultural get-away preference was dictated to you; you were told that you wanted to go to a tropical island in the ocean (never mind which one) that had a sandy beach and some palm trees. Now, no one wants to go to that island anymore – too many tourists. Nor does anyone go to the movies, watch television or listen to the radio for the purpose of having their cultural fantasy-land directly prescribed to them – if they even consume that sort of media at all. Then there is the problem of who that consumer is, who flees her own circumstances. The identity of a consumer is perhaps best understood not by the medium of the escape, but its cause: politics. With class-consciousness in torpor since the 90’s, the most useful way of understanding political affiliations today resides in the recent populist referendums, Brexit being the premier example. So, after Brexit, where do British people go in their minds when they try to escape their fractured national political scene?

The losing Remainers have already chosen their preferred cultural get-away, both in terms of gastronomical and fictional sustenance. Even before the referendum that so firmly shook the British polity’s political elites and their supporters, there was a cultural dividing line. It is drawn like this: wherever you find an establishment that is fixated on Scandinavian culture, then you have found a Remain stronghold. Some say that the way to understand the current political spectrum is to think in terms of ‘centre and periphery’, but how do we understand which town is which? While statistics might prove useful, one does not live statistics; one can however gobble down a cinnamon-bun and a cup of Gevalias-coffee. Or why not have pint of Carlsberg and call it a Hygge? When about town, search for cafes or bars that coast on ‘Scandi-mania’ and rest assured that you are safely ensconced in remain-land where good moral values prevail, and Britain remains an important actor in the international community. Edinburgh, where I live, makes no secret of its preoccupation with Scandinavian culture, boasting up to 9 Swedish themed bars, 5 Scandinavian cafés, several Hygge themed pubs and a Scandinavian store that offers access to all the right Scandi-branded products such as the popular Fjällräven backpacks. Then there is the expansion of IKEA throughout the UK, delivering cheap but aesthetically pleasing furniture. The latest expansion taking place in northern England, where the second largest IKEA store yet is being constructed for an estimated cost of £60 million.

Why does the British middle class turn to the Nordic cultures for the decoration of their homes and stuffing of their mouths? When the mega-hit video game Skyrim was released in 2011, there were suggestions in the internet commentariat that the game’s Viking-age setting and aesthetic resembled Richard Wagner’s hyper-romanticised and hyper-racialized operas. The implication was that the consumption of Nordic-themed games equalled a form of cultural ‘white-flight’ from reality. Such observations seemingly assume that we live in a re-hash of the Viking-craze of the mid- to late 19th-century when nationalists of the European superpowers of Great Britain and the newly formed German state fought over the claim of Viking-heritage. British propagandists claimed, for instance, that Queen Victoria was descended from the Viking chief Ragnar Lodbrok. Viking-heritage, having been cleverly assembled and packaged for export by Scandinavian national-romantics in the 1820’s, was a good historical fable of political relevance from authors who nationally belonged to a geopolitically irrelevant part of imperial Europe. But the rise of right-wing nationalism does not seem to be a great explanation for the new interest in Scandinavian culture. Viking narratives have even less impression than Scandinavia’s geopolitical influence. Not even nationalists pay heed to them anymore. Today’s radical right, especially the British variation, have no demand for an imported mythical past. They are already saturated with the fictional retelling of their national history in HBO’s Game of Thrones or why not Ridley Scott’s Whiggish telling of Robin Hood (2010). No need for Viking stand-ins there. Incidentally, this is the case for most right-wing movements in Europe. They’ve successfully seized the means for producing their own mythical past, not needing any horned helmets or runic tattoos. In any case, these Scandi-focussed Remainers don’t tend to this kind of right-wing nationalism.

We are not dealing with a desire for a mythic Nordic past but something else completely.

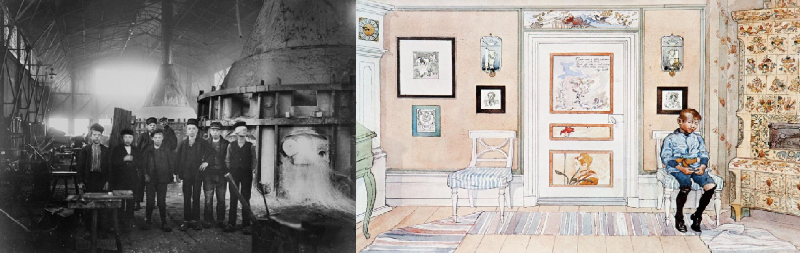

A brief glance at the design and presentation of most Nordic products informs us of what appeals to the British consumers. Open, bright spaces and minimalistic design that maintains a sense of rustic warmth. This is the design that is presented at both IKEA superstores or your nearest Nordic café. A place beyond plastic, swept in knitted wool and packed in brown crinkly paper with your name written in charcoal on the parcel. Rough wooden design furniture, juxtaposed against crisp white walls in a large studio apartment. Christmas with hot cocoa but minus the anxiety inducing consumption. In other words, a world that is a complete fantasy with no substantial ties to reality. It is however a good place to visit in the mind, a place safe from conflict and social ills. Swedes have tried the reconstruct this utopian vision since the early 1900’s. In the paintings of Carl Larson, the bright and open space was conceptualised and constructed for eternal reproduction. The Swedish middle-classes’ love affair with this aesthetic has aided them well both in terms of fleeing from the political scene during the aegis of social democracy in the 40’s to early 60’s and also financially in exporting their shining delusion. IKEA, founded by the 17-year old fascist Ingvar Kamprad in 1943, perfectly encapsulates the most economically successful iteration of the Swedish middle-class flight to the bright. Again, to say that this corresponded with the reality of Swedish material circumstances is untrue. Five years prior to the founding of IKEA, radio journalist Ludvig ‘Lubbe’ Nordström published one of Sweden’s first long-form radio reportages that described the country as having the worst living standards in Europe. Travelling from Malmö in the south to the northern border-town of Karesuando, Nordström portrayed the conditions for the Swedish peasantry and working classes; “I saw people co-habit with animals, I saw people live in decrepit houses, I saw people sleep in what must be called holes or caves”. Another study by the social-democratic authors Alva and Gunnar Myrdal concluded in 1934 that “Overcrowding in Swedish cities is considerably larger than in comparable countries in terms of wealth and cultures. The most common size of a family apartment is a one room and kitchen flat, or even smaller in size”. The Myrdals’ and Nordström’s Sweden was far removed from the cosy proto-hyggen that the middle classes were constructing in their apartments and summer houses. On the other hand, the reformist texts signalled a larger political trend that called for worker-oriented, long-term social planning. Today, Kamprad’s vision for IKEA is alive and well, bright flight being available in 26 countries and three continents. In contrast, the Myrdals’ and Nordström’s social planning is currently expiring in the conference rooms of today’s dying social democratic parties. Though Corbyn may have energized a reformist left in the UK, no such luck is to be had for Labour’s Nordic counterparts. The Swedish social democratic party is currently projected to lose this year’s election, finishing below the 30% bar for the first time since 1920. Did the Scandinavian middle classes, having regained full control from the pesky workers with their insistence on class-conflict as the basis for politics, relinquish their bright fantasies and self-consciously assume political power? No, the collapse of the workers’ movements and radical trade unions in the late 70’s and 80’s only increased the acceleration of consumption and the retreat from politics. It seems that the true blessing of Scandi wool-blankets, either bought at some exorbitant price at hip urban retailers or cheap IKEA models, is its ability to muffle out the sound of political struggle.

Returning to contemporary Britain, the picture becomes clear if somewhat unnerving. Though the rupture of Brexit might make some think that Britain’s urban middle-classes will grasp the political and social consequences of the policies that have enabled their easy-living, the prevalence of Nordic products and goods signals no such awakening. The politically astute British consumers of Nordic bright flight may infer that the reason Scandinavia is conceptually popular is because of its generous welfare states. The implication is like Bernie Sanders’ dictum that ‘if the Scandies have functioning welfare, why not the US as well?’. In Britain, which unlike the US has a labour-oriented history, such propositions reveal the depth of the Scandinavian myth. To my mind, it is impossible to conceive of Scandinavian welfare states, which are currently being dismantled, without also taking the decades-long workers’ struggle to re-organise society into consideration. Do the Remainers truly wish for a renewed workers’ movement to transform society, or do they simply desire the end-product? Their fantasy of Scandinavia seemingly has no room for the social movement that will enable its existence. No, giving consideration to such political matters is counter-productive to consuming the Scandi-fantasy. The only struggle that is admissible to the “bright flight” is the struggle to realise its material continuation. Material, in the sense that there is not enough room in Britain’s overcrowded cities to accommodate the full experience of bright flight for all those who yearn for it. Our current political moment is that of a micro-managed interregnum due to the dominant class’s unwillingness to engage in any politics that requires its abandonment of cultural escapism. This is true of both Scandinavia and Britain. What is also true for both Scandinavia and Britain is the fact that broad nationally based, social movements are incongruous with the political upkeep of cultural escapism.

For the moment, Britain’s and Scandinavia’s middle-classes share similarities in consumptional taste but that will inevitably change. For those trying to clearly perceive our current political landscape, the middle classes are difficult to spot as a group due to their varying ideological desires and anxieties. Their wealth protects them from consequence, leaving them to consume various cultural trends. Meanwhile, spotting the working class is easy. Just look in the mouths of working people in Britain, the US or indeed in Scandinavia. Do not look for the content of their ingestion but the quality of their dentures. The pain of a deep cavity does not need the clothing of any foreign culture. One hopes that such a cause for pain will lead to a cause for action. Sadly, the concept of “hope” has since November 2008 been removed from the space of political practice and entered into a comfortable bright space where it will bother no-one. Bummer.

Per Rolandsson @pickibun