This week’s special article by Jimena Vazquez, reflects upon the last Mexican elections. Jimena argues that the election result signals that: ‘it is not only that we have condemned our country’s non existing democracy, but that AMLO has been able to channel such condemnation and transform it to a political message that gives citizens a hope that goes beyond the refusal of what Mexico is today.’

Mexico is a country where 43 students can be abducted and to this day, almost 4 years later, their families and loved ones are still waiting for answers and justice. In Mexico 3 film studies students can be tortured, murdered and their bodies dissolved in acid. Mexico has no social mobility: if you are born poor, you will die poor. In Mexico 50+ million of its citizens are surviving in poverty. There is an average of 7 women killed daily. Mexico is a country where it is extremely hard, almost impossible, to point towards a politician that has not been involved in a corruption scandal. The last 12 years in Mexico, since the beginning of the war on drugs, there have been a reported of 200,000+ people killed and 40,000+ missing. The Mexican government is so absent in most—if not all—parts of the country, that it is the families of those missing who try to find them. Mexico can be described as a clandestine graveyard. During this past election alone, over 100 candidates and election workers were assassinated. Mexico is one of the most dangerous places in the world to be a journalist, right after Syria and Iraq. Mexico is a country of death. This is the stage where the 2018 presidential election has taken place.

There is a striking similarity between the 2018 election and the historical importance of the 2000 presidential election. The year 2000 marked the end of the 71 year autocratic regime of the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (Party of the Institutional Revolution, PRI). Mexicans voted the PRI out of office, not so much for a trust in the alternative—the right wing Partido Acción Nacional (National Action Party, PAN) and its candidate, Vicente Fox—but more so because such alternative was able to canalize the rejection towards the autocratic regime. A similar sentiment can be signalled to in this recent election. Voting for AMLO on the 1st of July, as the candidate of the Movimiento Regeneración Nacional (National Regeneration Movement, MORENA), was undoubtedly fuelled by a rejection to the ruling system, much like it happened 18 years before. In the 2000 election, however, the rejection was focused on a single party. Fast forward 18 years, and while the denunciation towards the same party remains, the PRI (after having come back in office in 2012, via very questionable campaign strategies), this time the people’s discontent was also directed towards the two other major parties in Mexico: PAN and Partido de la Revolución Democrática (Party of the Democratic Revolution, PRD); the right and “left” wing party that formed an extremely cynical coalition for this election. Mexicans in 2018, thus, not only rejected a ruling party, but the established party system as a whole, in their understanding, that it was them that had allowed and contributed to the deadly scenario that characterizes Mexico today.

However, as much as the rejection towards the status quo played a fundamental part in this election, a sense of hope is to be highlighted. This time, it is not only that we have condemned our country’s non existing democracy, but that AMLO has been able to channel such condemnation and transform it to a political message that gives citizens a hope that goes beyond the refusal of what Mexico is today. AMLO has been the centre figure in Mexican politics for almost two decades. He was the mayor of Mexico City from 2000-2005, a position he left before the end of his term (with extremely high approval ratings) in order to run for the presidency, in 2006 for the first time. This election was extremely contested and controversial; to this day many believe it was a fraudulent one (less than a 1% difference in the vote between AMLO and Felipe Calderon from PAN, who ultimately became president). Next was the 2012 election, where the PRI made its come back. Indeed this time the difference between AMLO and the PRI’s candidate (Enrique Pena Nieto) was clear; however, the tactics and methods used by the PRI to tilt the election in their favour have been criticized. During all of these failed presidential campaigns trials AMLO did not stop constructing his political persona, which has remained to this day inspired by where he started: the margins. AMLO began his political career as director of The Indigenous Institute of Tabasco, the state where he was born. His voice, his worry and his message, thus, has always been about the marginalized ones and bringing justice to them; AMLO, through his political career, has mimicked the idea of a social leader. His message and his journey through Mexico, even if done under the ultimate objective of becoming president, were built upon an idea of justice that transcended everything that any other politician has ever hoped to offer the Mexican people. This is one of the aspects in which this election is unprecedented; it is the first time in Mexico’s history that we have elected a president who could be analysed as a leader of a leftist social movement. Hope.

AMLO’s construction of a social movement comes from his incontestable diagnosis of Mexico’s reality: corruption, poverty and violence are Mexico’s biggest problems. But the power of his diagnosis does not end there, his critical view highlights that these problems have not risen out of thin air; there are culprits, and he gladly points towards them: the oligarchical elite, or la mafia del poder (the power’s mafia) as he calls them. AMLO has not been afraid to point towards the injustice that the vast majority of Mexicans have lived under the current political and economic system. A political and economic system so broken that has provoked for millions of Mexicans to only experience poverty and marginalization during their lifetimes. At the core of this diagnosis we thus find a movement that is powered by the worry for those that have been forgotten in Mexico for decades. AMLO knows these forgotten. He has travelled the country in its entirety more than once (which is not something that any of the other candidates could say). AMLO has seen that Mexico is not one, but many complex realities. He is the only political figure who can say that has witnessed these realities, has seen them, understands them and worries about them.

His critical offering on Mexico’s complex realities allows AMLO to talk about Mexico’s social problems as no one has dared before. An example of this was how he talks on the evidently failed war on drugs, and showed that violence, criminality and poverty have become dangerously intertwined. In a country as corrupt and poor as Mexico criminality is more complex than a white and black spectrum. Such a spectrum offers no possibility for analysis, for example, in the case of farmers that have been forced, either out of necessity or coercion or both, to work in the drug planting “business”. AMLO pointed this out, and said that another option for Mexico’s drug problematic needs to be discussed. His opponents tried to sell the idea that this meant that AMLO was offering pardon to all criminal acts. False. It rather means that we have to acknowledge that in a country where millions of its citizens have been forgotten by their government, the time has come to accept that the state shares guilt and responsibility with its citizens’ tragedies. In a country where the government is not able to assure social and economic security for its citizens, it shares the fault when they turn to criminal acts out of need or coercion.

As AMLO talked about this and other matters he was named populist. Not surprisingly, populism in Mexico is mainly used in a negative and pejorative manner. In a nutshell, it is used for politicians that are seen to promise economic favours if elected and by doing so they are dismissing democratic institutions. But what the commentators voicing this critique fail to understand is that AMLO has not promised “economic favours”, but rather the assurance of political justice. Political justice for those who have been undeniably forgotten by the supposedly democratic institutions that in reality only serve a certain part of the population. A more productive discussion could be had regarding AMLO’s populism if we were to understand such a term as a political logic or strategy. If we were to take that route, we would undoubtedly tackle the need to understand the construction of the idea of the people, not directly done by AMLO, as he himself has said so. The people were built by marginalization, and their coming together has taken a long time. The people gathered as they understood they were governed by a system that did not care for their needs. And more and more has this “people” grown by the realization that, within their differences, they share the search for justice and recognition. Not all components of the people are the same, nor do they share the same type of needs. The student movement of 1968 is not the student movement of 2012 #YoSoy132 (#IAm132). The social movements of the 70’s drowned out by the government’s dirty war are not the same as the rising of the civil society after the earthquake of 1985. The particular demands and wanted solutions that respond to their particular marginalization are different, but still, the people have come together. And this is what AMLO attended to. He was able to offer a political message that gathered these differences and acknowledged them and channelled them into a message of justice and hope.

However, it would be naïve to present AMLO as a political figure without faults. As insistently as he says that corruption is Mexico’s biggest problem, he has never clearly spelled out how he will get rid of it. He argues that all it will take is for an honest president to assume office. But, as important as a moral compass may be for this cause, there is a little too much wishful thinking in hoping that just by mere example corruption will end in Mexico; especially so, when AMLO himself has brought into his movement a few questionable people. This leads me to another critique, his political pragmatism. How much pragmatism in the name of winning a campaign is too much? Many people worry, myself included, that he has promised too much in these pragmatic manoeuvres, and that he might find himself with a much reduced playing field from now on. So, no: AMLO is not without faults, we could write just as much about his contradictions as about his accurate and critical view of Mexico’s reality. But it is because of such critical view that those of us that voted for him, chose to overlook his faults. We hold onto this offering of a critical diagnosis because in doing so we are allowing for the millions of forgotten Mexicans to be acknowledged. We hold onto his offering because we know that we can no longer keep on the path of death and poverty which we have come to know so well. We hold onto such a view because of the very fact that at last someone seeking the presidency made Mexico’s tragedies the centre of his movement. We hold onto such a view because it gives us hope that someone actually envisions the possibility of a different Mexico, one that is not stained by tragedy.

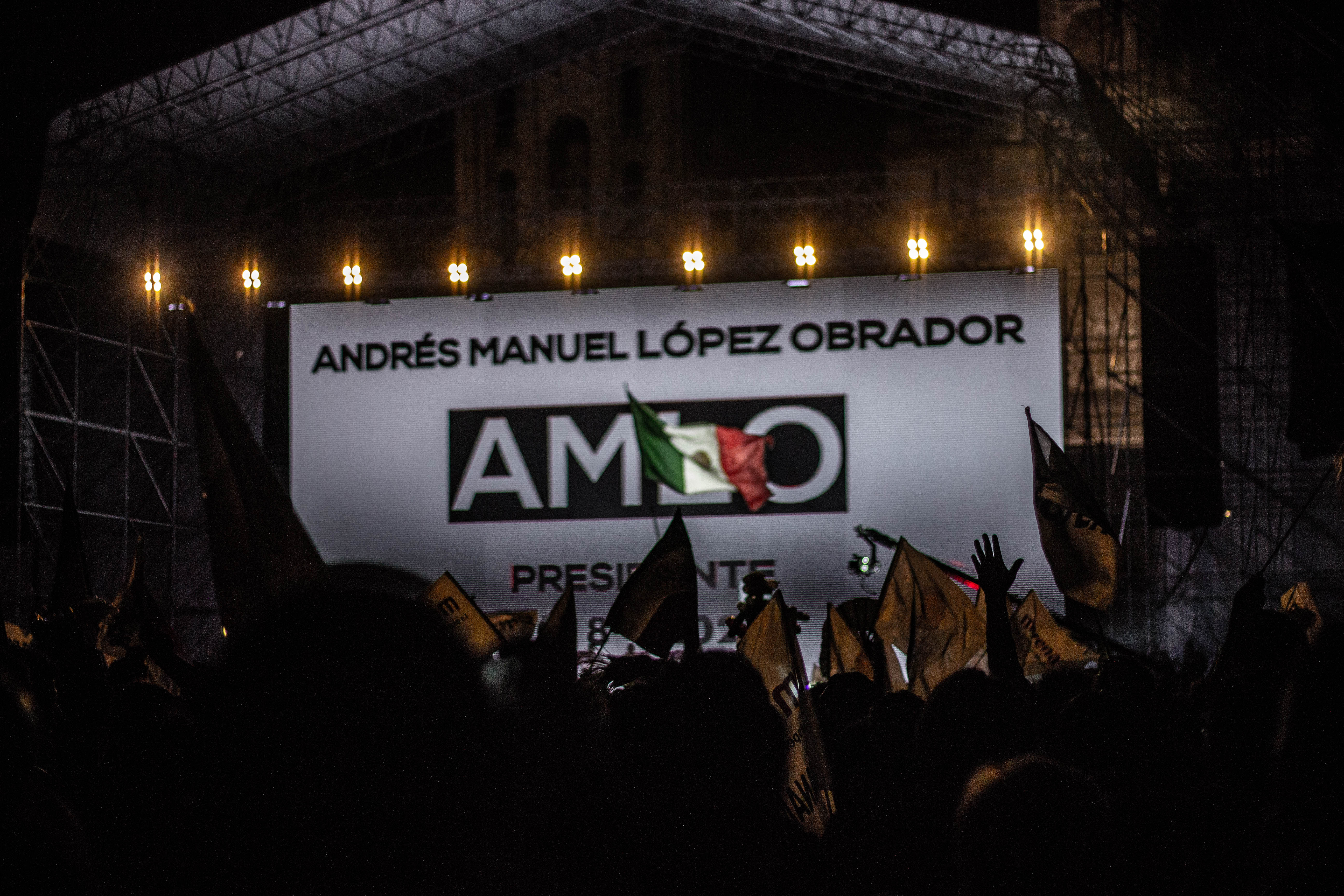

I remember the party that was Mexico on the night of the 2nd of July 2000, our supposed transition towards democracy. I can evoke the images of a packed Zocalo (Mexico City’s main square) filled with hopeful people. I can vividly see the face of a young man that had climbed a light post and was screaming and waving the Mexican flag as if his life depended on it. It was a party like no other. The disappointment, anger and hopelessness of the 18 years that followed drowned the party in its entirety. In the months leading to this election, I wondered if I would see the same party, if I would now be able not only to witness it, but actually understand the sentiment that filled the Zocalo many years ago. And indeed, I saw the party. I felt and understood the joy. It was a party louder and brighter than 18 years ago. It was a party brought about by a historic win with over 50% of the popular vote. It was a party fuelled by the realisation that for the first time ever in Mexico’s history a leftist candidate has reached the highest office. I am buzzing with hope. But I also now feel fear, as I know that the real work only just began. There is a part of me, and of many of the people celebrating alongside me, that is frightful of another disappointment, of another drowned out party. But, for now I will hold onto the hope of having elected a president that in his victory speech acknowledged the trust and hope that has been vested in him by saying that: “We will govern for all. But we will prioritize the forgotten ones, especially the indigenous people. For everyone’s sake, the poor will come first.” The poor will come first. It was about time. Hope.

Jimena Vazquez is a PhD student working on the idea of critique and subjectivity in Foucault at the University of Essex. She is a researcher at the Centre for Ideology and Discourse Analysis (cIDA) in the Department of Government.