The developments of the Irish General Election (2020) represents an historic juncture for the left in Ireland. The question of left-strategy seems more urgent now than it has in the past. This urgency can be located, not in the decline or failure of the left, but rather in its rise, as represented by the fact that Sinn Féin, the republican-left party, stands at 25% in the latest Irish Times Ipsos MRBI poll (4.2.20). In the same poll the Sinn Féin party leader, Mary Lou MacDonald commands a staggering 41% approval rating. This poll places MacDonald 11 points ahead of the leader of the old ‘civil war parties’, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, parties who have each governed the 26 counties since partition in 1921.

Leaving aside the considerable limitations to even the possibility of a Sinn Féin left-government – imposed by both the fact they are running only 42 candidates and that such poll’s margin of error and sample size present something of a distorted picture of the political landscape more generally – the parties popularity and standing amongst the electorate is at a historic, and largely unprecedented high. This decline in the consent to govern for the ‘civil war parties’, presents what must not be overlooked as a decisive turning point for left struggle on the island of Ireland. The hegemony of conservatism that has prevailed up until this point, most recently in its neoliberal articulation, has suffered a considerable blow. For the first time in the history of the post-colonial Irish state the possibility of a substantial left-hegemonic project is within reach.

Occasioned in part by Brexit, in further by the compelling leadership of TD’s Eoin Ó Broin on the issues of housing and vulture funds and Pearse Doherty on banking reform and insurance rates, as well as a change in party leadership with Mary Lou McDonald, Sinn Féin’s rise in the opinion polls builds upon years of effective and substantive community organising across the island of Ireland. In the midst of the worst housing and homelessness crisis in the history of the island the party has presented the only sensible and meaningful plans to tackle homelessness, rising rents, substandard construction of houses and property taxation which puts ordinary people and not property developers and high earners first. It is becoming increasingly clear that Sinn Féin has capitalised on the populist energies that stand as a delayed effect of the 2008 economic crisis. In the absence of any real political change, continued austerity and the further deterioration of standards of living, rising house prices and rents, citizens are turning to the only viable anti-establishment party offering leadership on these matters.

The mainstream media and political parties have gone to great efforts in painting Sinn Féin as not a ‘normal’ political party. Undermining the democratic credentials of the party with recourse to tropes of ‘shadowy figures’ pulling the strings (read here IRA army council) and making much of the ambivalent relationship between Sinn Féin and the IRA in the struggle to end to British rule and partition on the island of Ireland. At stake in these ongoing attempts to ‘other’ Sinn Féin is the very refusal of the parties of the establishment to recognise the post-colonial history of the island. As David Lloyd put it in the late 1990s, to name the Irish state as post-colonial is to put into question, not only the legitimacy of British rule in the six counties, but also the institutions and distribution of power established through partition. Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael are that history, at the origin of this fundamental political and economic inequality. In a deranged article published in the Irish Times on February 5th 2020, Senator and former Attorney General Michael McDowell rehearsed all of the above mentioned tropes, going further to accuse the party of betraying ‘western political values’ in its criticism of US involvement in the political affairs of Venezuela. The key message of McDowell and the establishment figures who presently profit from the growing inequality and political consensus around the centre-right of the political spectrum, is that Sinn Féin is not a normative or ‘conventional political party’. That much is true insofar as Sinn Féin represent the interests of the people not included in Leo Varadkar’s ‘Republic of Opportunity’ or Fianna Fáil’s NAMA phonebook.

Sinn Féin, rather, is a broad political alliance, which has historically brought together members from across the ideological spectrum, under a leadership which has largely been socialist and progressive (the party’s own Eoin Ó Broin has done a compelling job in chronicling the history of The Politics of Left Republicanism in his book by the same name, such that I need not go into detail here). As a broad alliance bringing together liberals, socialists, community activists, and trade unionists under the banner of ‘Republicanism’ and a ‘United Ireland’, Sinn Féin has managed to channel diverse and disparate elements of a populist energy into a progressive force struggling for political renewal and reform of the two states on the island of Ireland at both cultural and constitutional levels.

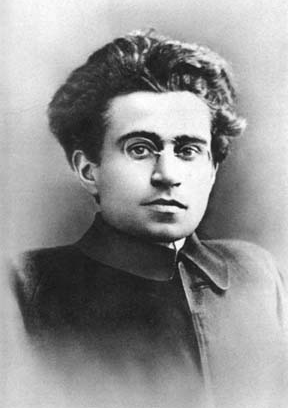

Many on the Irish left have criticised Sinn Féin for simply being nationalists, disinterested in socialist internationalism and interested in taking over the Bourgeois Irish state. Enamoured still by the Jacobin imagination of revolutionary politics, much of the Irish left mistakes tactics for strategy. Sinn Féin, and any other radical struggle for democratisation and equality that passes through the grammar of Republicanism, knows full well the lessons of Gramsci. The state, as we (post-)Gramscians attest, is but a site of political struggle among many. Taking up a strategy premised upon the logic of a war of position, it is only through the transformation of the state through struggle within it, that the politics of left-hegemony can establish its durability and hold on power. Such a view departs from the orthodox Marxist interpretation of the state as an actor in and of its own right, with a fixed essence. Building a left-hegemony requires mobilising both within and without the state, not it’s destruction.

Many on the Irish left have criticised Sinn Féin for simply being nationalists, disinterested in socialist internationalism and interested in taking over the Bourgeois Irish state. Enamoured still by the Jacobin imagination of revolutionary politics, much of the Irish left mistakes tactics for strategy. Sinn Féin, and any other radical struggle for democratisation and equality that passes through the grammar of Republicanism, knows full well the lessons of Gramsci. The state, as we (post-)Gramscians attest, is but a site of political struggle among many. Taking up a strategy premised upon the logic of a war of position, it is only through the transformation of the state through struggle within it, that the politics of left-hegemony can establish its durability and hold on power. Such a view departs from the orthodox Marxist interpretation of the state as an actor in and of its own right, with a fixed essence. Building a left-hegemony requires mobilising both within and without the state, not it’s destruction.

Our argument is not one for left-nationalism. Nor is it an uncritical support or commitment to Sinn Féin as the vehicle for political change. The global and particular inequalities we face today extend far beyond the nation state. And, to be clear, in our estimation Sinn Féin is not a ethno-nationalist party, but rather a radical democratic alliance pursuing a populist logic of articulation in opposition to the Irish political mainstream and the latter’s investment in the continued colonisation (of both north and south) and partition of the island of Ireland. Irish-Left Republicanism articulates a solidarity with those opposing state violence and inequality be it in Belfast, Dublin, Palestine, South Africa or Rojava.

What’s more, as socialists and internationalists, we must refuse the racializing, and essentialising logics of left-nationalist arguments, arguments which are tied all too often to notions of popular sovereignty in which ‘the people’ as constituting power are rendered coterminous with the nation as ethnos. A radical democratic and left politics transcends methodologically nationalist arguments. The argument we make here, is more straightforwardly put in terms of building a left-hegemony on the island of Ireland. The state and it’s electoral mechanisms, the product of our post-colonial condition, are not the only site of political action and democratisation.

So, then, it would seem that Sinn Féin is a party and movement haunted by the ghosts of its republican past. It seems a heavy-load that the establishment commentariat are only all too willing to increase come election season, and find no small measure of contentment in watching the party buckle and falter before they reach their potential. This is not quite the full picture. For it is not the republican ghost that stalks Sinn Féin, but rather it is the republican ghost that haunts the establishment. It is the spectre of equality, and the naming of a wrong, that frustrates and shows the very limit of Irish political regime. Much of the popular political grammar throughout the country and its history, when mobilised to express political grievance, is a distinctly republican grammar. The ideological inability of Fine Gael and their coalition partners Fianna Fáil, to solve the housing and health crises for example, violate the republican promise of equality. These wrongs, these trespassing’s against minimum decency, are easily articulated through a popular republican political imagination. And for many for the establishment hacks, therein lies the rub. They are offended by a left-Republican political project, not because the ‘numbers don’t stack up’ or Sinn Féin are promising too much. Put bluntly what offends the ruling parties and the sympathetic press is the promise of equality. Fine Gael’s leader Leo Varadkar, for example, in a well-known campaign, declared the party as that which ‘represents people who get up early in the morning’. For some, this was innocuous enough, those who work hard see the results and government should not be a fetter around the necks of the hard-working back bone of the country. For others this underlines the political subjectivity that Fine Gael represents; the individual, going it alone, hacked off from society. Many would argue this political subject is grounded in a vision of meritocracy. But it is a vision that tacitly (or in fairness when it comes to Fine Gael not so tacitly) legitimates and deepens the logics of inequality and social exclusion the party covets. In other words, this neo-liberal political vision violates the republican promise of equality. Many voters (whatever the final poll), implicitly at least, know this. They know that governing parties are ideologically incapable of pursuing an egalitarian vision of society. Whatever the failings and limitations of Sinn Féin, they have put themselves forward to be judged and be held accountable by their republican political imaginary, the spectre of equality. And of course, the cheerleaders of a Sinn Féin slump, to many voters, then, appear as the cheerleaders seeking the death of a long-standing egalitarian promise.

What disturbs the ‘centre’ ground of Irish politics is that a truly left-egalitarian project cannot be fully accommodated and exhausted within routines and rituals of Irish political life. It opens up ever-new arenas of egalitarian struggle. Here we stumble upon the philosophical distinction between politics and the political. Politics concerns the reproduction of a regime of power, the political highlights its limits. Left-Republicanism haunts the ‘centre’ precisely on account that it reveals the very limits of the established order of things. Left-Republican struggle is a hegemonic struggle, that is a political-cultural battle that re-negotiates what is politically possible. We have seen attempts throughout the ongoing decade of centenaries events which commemorate the events that led to the founding of the state to tame the republican ghost. Much of the foundational events of the Irish State were republican and socialist in character. Yet, many commentators and politicians seek to bracket these foundational moments, under the rubric of ‘mature reflection’. Thinking the Republic however is thinking the political. It is to bring into relief the long histories of the negation of the republican promise, and the foundational violence of the two states on this island. It is to articulate a vision of the future that seeks to redeem the promises of the past. It brings into to question the very ground of the established order. This is not to be shirked, rather it is what lends republicanism it political potency.

The emergence of Sinn Féin as a major political force in electoral political projects thus signals on our reading, not simply the possibility of a left-hegemonic project anew, that is for left politics, but more fundamentally the re-emergence of the political itself. As Chantal Mouffe has argued, neoliberalism’s hollowing out of liberal democratic politics, and the destruction of the political, that often antagonistic face-off between competing conceptions of society, has meant that voters have had no meaningful alternatives to the status quo that renders them poorer, powerless, and without hope in electoral politics. It is this space vacated by the old parties of the left, that the rise of the far-right has been made possible, and racists has flourished.

The current re-emergence of the political, occasioned by the viability of a left-hegemonic project that is Sinn Féin, provides Irish voters for the first time in these authors life-times with a political alternative that materially challenges the cosy consensus of Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael and their neo-liberal hegemony in ruins. The possibility of the transformation of the constitution of the state in a left-wing direction ought to be be the ultimate concern of any socialist politics on the long-term temporality of strategy. In the short term, a left-government would go a large way to addressing many of the greatest issues of inequality in the ‘free state’. The Sinn Féin project, now gaining momentum, offers us a renewed political grammar and terrain upon which we can begin to fight this battle proper.

The republican political imaginary, then, as we have argued here, still carries an emotive ruptural force. Throughout our history it has periodically returned to intrude upon the established routines of Irish politics. Any progressive political project, that seeks to elevate itself beyond that of a single issue campaign, needs to take account of and accurately survey the terrain of political struggle in which it finds itself. The colonial and post-colonial histories that have played out and shaped this island have bequeathed us a particular grammar of struggle. Many on the left have for too long dismissed this republican political idiom as an impoverishment and an obstacle towards the realisation of a truly radical emancipatory project. By our reckoning, such a dismissal denies much of the Irish left (who no doubt have pursued a noble politics), of a vital grammar of equality that has popular traction. Worse still, such a denial of the potential of a left-wing political grammar opens up space for the alt-right to take up and usurp this grammar. A quick glance through doldrums of far-right Irish social media (we recommend you don’t), reveals a smattering of zealots who are seeking to mobilise the language of republicanism towards grotesque xenophobic ends. Of course, for now the Irish alt-right are hampered by incompetence matched only by their stupidity. But that may not always be the case. Fools can learn. To vacate the space of republicanism is to surrender it to who those who delight in the worst of all possible worlds. This includes a deepening of the neoliberal project. Instead, the imperative is to pluralise our political grammar, to deepen and widen the spheres of social inclusion. After all, as Irish President Michael D. Higgins (hardly a hard-left fundamentalist) insisted in 2018 during the inauguration speech of his second term as president: ‘We are at a time of transformation and there is a momentum for empathy, compassion, inclusion, and solidarity which must be recognised and celebrated’. He continued ‘a republic after all is a life lived together’.

Liam Farrell is the co-editor of The New Pretender and a critical political theorist researching the politics of equality, democracy and power. Gary Hussey is a social theorist researching political violence and conflict.