In this article, The New Pretender interrogates the racial dynamics of the Repeal the 8th campaign in Ireland through an analysis of the centrality of Savita Halappanavar as an icon to the campaign. We look at how neoliberal registries of governmentality cast different meanings of what it means to be human over migrants, particularly migrant women of colour, when it comes to healthcare and access to it. Savita Halappanavar is a young Indian migrant woman who died in 2012 after she was refused an abortion at University Hospital Galway. By Jimmy Billings and Vedanth Govi.

On Friday the 25th (polling day), I (Jimmy) was out at some different locations in Dublin handing out campaign literature and making the final push for a Yes vote. What was made very visible to me, as a masters student whose area of interest is race and migration, was the whiteness of people accepting material and confirming their vote — or rather the people of colour that visibilised the racist boundaries of citizenship who avoided eye contact or apologetically said they didn’t have a vote. To me clearly there is a need to see the absence of voting rights in this scenario beyond narrow abstractions of citizenship, supposed blood rights and notions of belonging: it boils down to women that live in the country not having a say on an issue of great magnitude that directly affects their lives. The same women of colour that had no say in the referendum have also suffered inordinately more as a result of the 8th amendment, with 40% of maternal deaths in Ireland being migrant and ethnic minority women despite migrants making up only 17% of the population of the country.

As an Indian student in Ireland, my conversation with Jimmy as a friend and colleague whose interests in decolonising knowledge systems I share, our conversations in the week building up to the referendum always came back to Savita Halappanavar who has been transformed into a symbol of the campaign. Savita was one such migrant/non-citizen woman who didn’t slip into the obscurity of a statistic, and the gravity of that fact is not lost on me as a fellow Indian. The fact that Savita’s succumbing to the trauma of her crisis pregnancy occupies the spotlight in the international media only reveals the fissures of how the repeal campaign has been racialized as a function of a neoliberal political ideology. In neo-liberal political ideology, the framework of multiculturalism serves a particular cultural purpose of creating categories and hierarchies of racialized migrants. Savita Halappanavar is a symbol of better reproductive healthcare in Ireland not despite but because of her racial identity. The image of Savita that pushes her into iconicity is one that avowedly marks her as a Hindu Indian woman. In other words, in the neoliberal framework of multiculturalism, she becomes the good Indian migrant. It is a form of multiculturalism that doesn’t account for the fact that her being rendered a good migrant may have much more to do with the structural privileges that are constitutive of Savita’s positionality. As an Indian, I can only try and delineate the fact that the upper-caste, middle-class, Anglophilic social and cultural capital that Savita accumulated over her lifetime effectively made her very similar to her white Western counterparts. It is interesting to note that the Yes campaign implicates itself in a framework of neoliberal multiculturalism by showing such a strong recognition of Savita’s gender but ignores her race/ethnicity, thereby rendering her the relatable cultural Other.

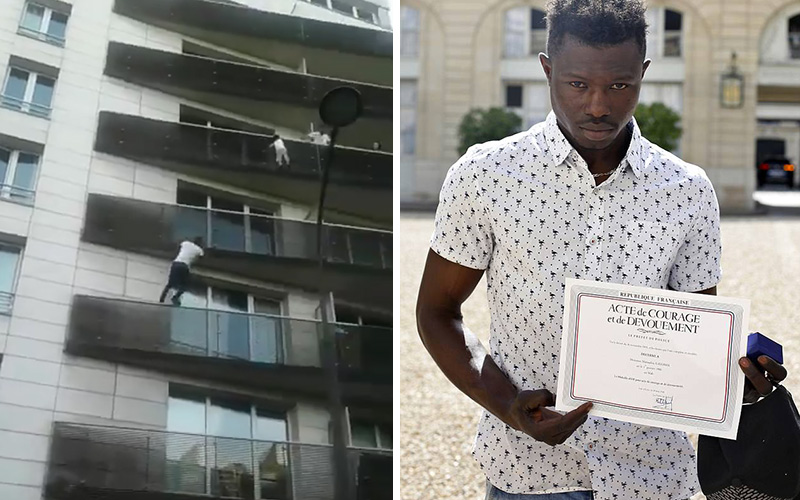

Two days after the results of the referendum were declared, the international news cycles have been dominated by how Malian migrant Mamoudou Gassama was offered French citizenship as a reward for saving a baby dangling down from a balcony in Paris. The headlines surrounding the incident may appear to be completely unrelated to the news of the repeal of the 8th amendment in Ireland but a closer inspection will reveal that Mamoudou Gassama’s catapulting into fame by the international corporate owned media belongs to the same socio-cultural registry that has displaced and mounted the reproductive anxieties, regulatory regimes, and solidarity movements that articulate claims for more equitable terms of reproductive justice in Ireland onto Savita. This is a registry of neoliberal governmentality in which citizenship is a negotiation that is increasingly constructed as a reward that is offered to migrants of colour in transactory terms. In Gassama’s case, it is through the performance of the sheer fungibility of his own body in service of the French state to save a white French baby that he is rendered the model immigrant citizen. The performance of Gassama’s willingness to put his own life at risk for a natural (as opposed to naturalised) French citizen becomes the bargaining chip with which he can negotiate for greater access to protection under the French state. In Savita’s case, it is her ‘martyrdom’ or the fact that her body becomes the metaphorical site through which generations of white Irish feminists have been able to mobilize a clarion call to rally around negotiating for better abortion laws that she is deemed ‘worthy’ in the registries of neoliberal citizenship. Clearly the logic of such neoliberal governmentality has inscribed itself within the feminist struggles for greater reproductive healthcare systems in Ireland. We cannot view this issue through a monolithic and reductionist understanding of gender oppression bereft of an analysis of how multiple oppressions intersect and compound the everyday lived experience of death that haunts the most marginalised and excluded in our society. Savita was not just a woman, but a migrant/non-citizen Indian woman. These facets of who she was (her gender and race) are irreducible from each other and there shouldn’t be a hierarchising of which facet comes before the other. To ignore the multiple oppressions present in the struggle for reproductive justice and bodily autonomy, or to fail to foreground them in the writing of the abortion legislation in the coming months, is to effectively contribute to that exclusion.

If there is no struggle for racial justice, the naming of the new amendment in honour of Savita will amount to a hollow gesture that lends to neoliberal multiculturalism which has no material basis. Migrant/non-citizens continue to face disproportionate difficulties in accessing basic healthcare services. In neoliberal registries of multiculturalism, states across Europe are seen to be constructing a migrant subjectivity in entrepreneurial terms where one is held responsible for how their own status as Human emerges within the State. Therefore neoliberal discourses engender a culture of racist amnesia to the very structural inequalities that the same State produces that put migrant women of colour at a disadvantage in the first place. State policy may be named in Savita’s memory as a woman affected by the 8th amendment, but will it lead to maternity services where migrant women of colour, that don’t enjoy the position of the good immigrant woman that Savita did, will not experience racism or discrimination? Recognition of such is something that needs to be struggled for as the Yes vote has been, but not left solely and crudely to those affected by exclusionary politics. Policy change does not necessarily indicate at a wider societal level that there has been a distinct change in the hearts and minds of people, which is not by any means meant to discredit the overwhelming response in favour of repeal. More crucially on a material level, policy and legislative change do not always mean a change in the lived experience of people. At our current historical moment in Ireland, it has been established that particularly young people want to have a direct say in decisions that affect their lives. Now we must collectively consider how to address the multiplicity of exclusions that exist in Irish society. There is a necessity for conversations that are now happening around gendered violence and misogyny to be coupled with racial violence. Migrant women will continue to experience barriers to healthcare access like cervical smear tests due to not having Personal Public Service (PPS) numbers. One of the ways in which the Yes campaign is losing out by not acting in solidarity with migrant women of colour is that it is allowing the pro-choice movement and its singular focus on abortion to effectively narrow the terms along which reproductive justice can be defined. By including migrant women of colour in the national conversation there is the potential to widen the scope of what reproductive justice entails.

The continued violent reality of the Mediterranean and Anatolian crossings to Fortress Europe shapes the lived existences of all migrant women of colour within European borders.

Death is the experience that shapes the very entryway to Europe for migrants mostly from Africa, the Middle East, and Central Asia. The treatment by European states of these migrants (drowning, detention camps, walls) means that even the ‘birth’ of a migrant’s European life is marked by death which they are effectively seen to deserve, as EU policies shape and enable this spectre of death. Healthcare is a social marker that ensures migrant women die differently by having no or impeded access to it. In the case of the Irish repeal campaign, a recognition and thereafter an attempt to counter such neoliberal governmentality which asks for evidence of worthiness from migrant women of colour must be made through grassroots activism. Until then, Ireland is responsible for the death of a Savita every second not just because of a reproductive healthcare system that is controlled by the Catholic Church but also by the structural racism that it doesn’t account for.

Vedanth Govi is a Masters student of Cultural Sociology at the School of Sociology, University College Dublin

Jimmy Billings is a Masters student of Race, Migration, and Decolonial Studies at the School of Sociology, University College Dublin