In this article Hasret Çetinkaya reports on Judith Butler’s recent Agnes Cuming lectures at University College Dublin in January 2019. Çetinkaya’s article exceeds simply a report, and in and of itself is a plea for the revolutionary implications of the politics of non-violence Butler proposes both in her most recent writing as well as her public lectures. ‘Anti-capitalist, feminist, anti-imperialist, and radically democratic, Butler’s latest work has forced us, in a time of increasing nationalism, patriotic populism and the individuated-ness of precarity under neo-liberalism, to recognise the urgency to act globally, and to think of new forms of political obligation, not to the state, but to the world, and the global responsibilities that entails’.

Judith Butler – a clown or a philosopher? The two options she found attractive when asked what she wanted to be as a child. Both are not too dissimilar. They can each bring you to an imaginary place in which your problems, or those of our world, are forgotten, or they equally may confront you with a truth you’d rather stay without. Butler is the kind of clown that takes you elsewhere, she’s the philosopher that deliberately brings you, not only academic insight, but also a sense of hope for what can come, instead of the rise of human meanness. She dares to ‘elevate principles that seem impossible, or that have the status of the impossible, to stand by them and will them’ (Butler in Filar, 2014). And what would happen if we lived in a world with no clowns, with no philosophers, with no one that held open such a possibility?

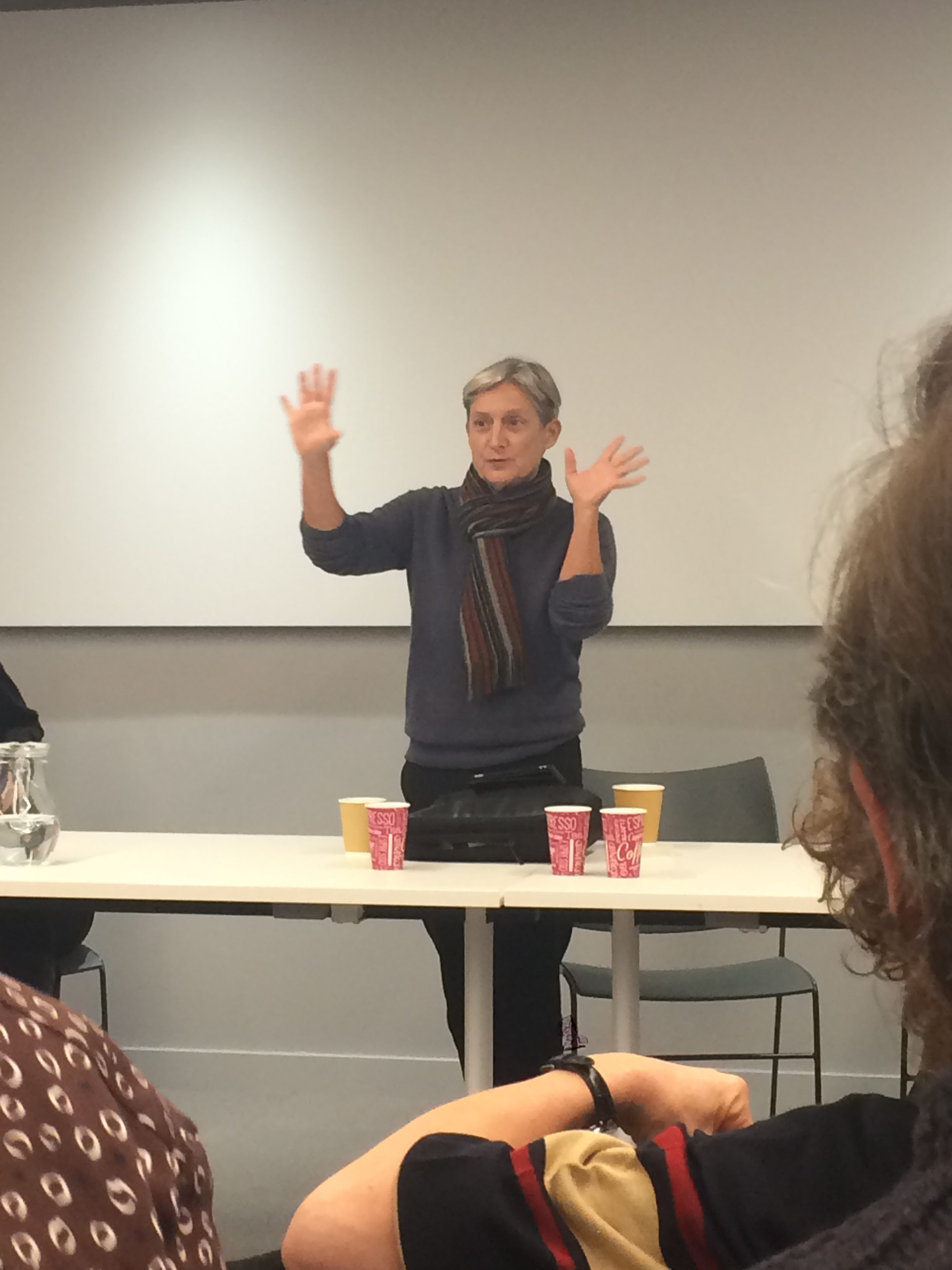

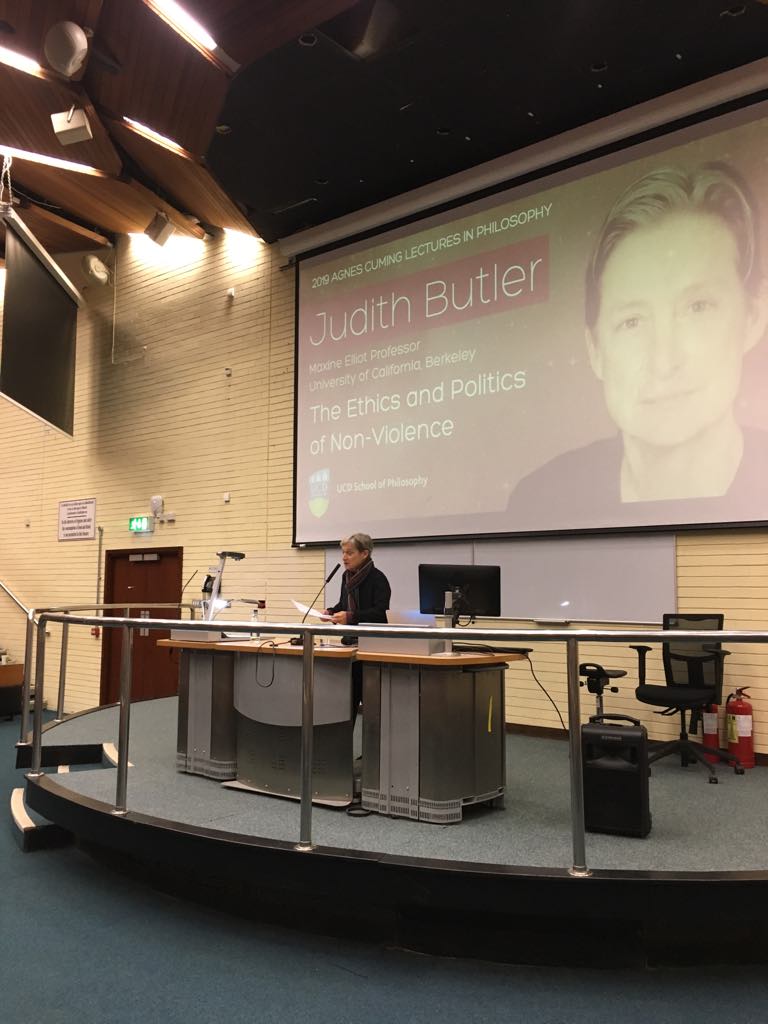

This article is a re-telling of what some might consider a clowns account of the ethics and politics of non-violence, and others, may simply see it as a presentation given by Judith Butler, an “improper proper” philosopher. On the 29thof January 2019, Butler delivered the first of two public lectures: entitled ‘Equality, Grievability and Interdependency’, as part of the annual Agnes Cuming Lecture at University College Dublin. In a huge lecture hall packed full of people on an icy cold Dublin evening, Butler gave an account, which left the majority of the people in the room with various ideas of what she was advocating. Was Butler preaching about an aggressive form of non-violence? Militant pacifism? Or was it, as she called it herself a ‘militant humility’, which will keep us together whilst fighting destructive powers? These names each point to the same. In her assertive, dedicative and calm voice Butler was not shying away from stating our political collective responsibility and obligation towards one another. Butler was doing what philosophers traditionally don’t: she did not police herself to the boundaries and understandings of a self-sufficient discipline, instead she was preaching for social change, knowing well her theory is tied to a political agenda, and cannot be separated from the outside world (Sandford, 2015).

Ethics and politics are not here conflated but require one another if we are to speak and engage meaningfully with non-violence. Butlers argument for a politics and ethics of non-violence, as presented in Dublin on thatcold Tuesday evening, has three parts. Firstly, it requires an analysis of inequality to obtain a politics of equality. Secondly, such a politics cannot be based upon individualism, as this negates the grievability of all forms of life. Thirdly, the arbitrary and strategic inversion of what is violent and what is non-violent needs to be challenged without falling into a form of relativism. The normative claims put forward by Butler must be seen in light of the increasing right-wing sentiment globally, the election of authoritarian leaders, the ever-present scene of racism, misogyny, homophobia, transphobia, as well as other mechanism of violence: objective, symbolic, and subjective. She argues that such violent discourses negate the possibility to see all lives as equally liveable or grievable, and thus foster an experience of increased exposure to vulnerability under conditions of precarity.

‘Precariousness,’ for Butler ‘as a generalised condition relies on a conception of the body as fundamentally dependent on, and conditioned by, a sustained and sustainable world; responsiveness – and thus, ultimately, responsibility – is located in the affective responses to a sustaining and impinging world’ (Butler, 2016). Thus, she has taken up the role of an engaging public intellectual and radical democrat, that sparks debate in how we organise ourselves, our ways of living and how in doing so we either sustain or oppose violence.

The ethical demand arises for Butler out of the fact that we have to live with one another, even with those we despise, so how do we create a world based upon solidarity, build upon our differences, and yet remain united in our shared vulnerability. Can this come to effect through the reality that we dictate, one premised upon a form of living, which constitutes a performative effect of our stance? A stance, which enables liveable and grievable lives for all. This is not a “right to life” argument, but rather one that pertains to the social conditions in which life can be lived. So, the ending of a life crossing the Mediterranean-sea causes as much sadness and political action, as the death of an ordinary man in his office, because of a gas leak. The latter life is considered hyper-grievable, whereas the life crossing the sea from Africa to Europe is ungrievable. ‘An ungrievable life is one that cannot be mourned because it has never lived, that is, it has never counted as a life at all’ (Butler, 2016). It is in such hierarchies that the lethal form of social inequality is witnessed most explicitly.

Central for Butler, therefore, is the starting point and commitment to a substantial form of equality, which safe-guards all lives, and similarly seeks to equalise the grievability of all. It emerges in her account as a question of responsibility. ‘Am I responsible only to myself?’, she asks, or ‘Are there other whom I am responsible? And how do I, in general, determine the scope of my responsibility? Am I responsible for all others, or only to some, and what basis would I draw that line?’ (2016) Subjects of social inequality are those whose lives are measured by different modes of valuation, and such a scene of violence is pervaded by the ungriveability of the acts affected. This is the basis upon which Butler seeks to imagine new and continuing grievability, to an egalitarian imaginary and a study of the modes of disavowal of such violence.

But even more radically, this is also an obligation towards those we do not know, those we are not related to. Butler asks in Frames of War: ‘What is our responsibility toward those we do not know, toward those who seem to test our sense of belonging tor to defy available norms of likeness? Perhaps we belong to them in a different way, and our responsibility to them does not in fact rely on the apprehension of ready-made similitudes’ (Butler, 2016). It is not communitarianism that Butler argues for, such blocks the possibility of a global view, but it is the need to critique individualism, to see that interdependency is central to our lives in a global frame. What this means is that enacting violence against another essentially is a form of violence against all our social bonds. Relationality of dependency is taken to its radical ends. First, we need to acknowledge that we are all bound up with the lives of one another, and only then will we be able to conceive of an approach of non-individual equality.

Central to Butler’s account in this talk, and elsewhere in her published works is the question of grief and the political power of mourning, in furnishing a sense of political community, emphasising the relational ties that point to the very forms of dependency and ethical responsibility she seeks to respond to politically. In this sense public grieving is a political issue of great importance as ‘open grieving is bound up with outrage, and outrage in the face of injustice or indeed of unbearable loss has enormous political potential’ (Butler, 2006, 2016).

The critique of Hobbesian individualism, Butler offered,is a valuable one, even if not new. One that cannot be repeated too often, as Hobbes is still to be found as part of all our curricula and modules – his ghost is ever present lurking in the background, reminding us that in the state of nature, the state of man will always be in conflict with another man, all aiming to fulfil their selfish needs. This origin myth is characterised by a society of disorder and war, and this political theology is framed in such a way that such a society pre-exists the subjects’ emergence. Such a fiction and phantasmatic scene, which organises our world and imaginary is one where the human from the start is a man. This man has never been fed, never been a child, never been dependent upon kinship, or even a mother to exist – he exists merely as an always already upright, capable, adult without relations. Consequently, an annihilation has taken place – an inaugural violence – a slate wiped clean. The state of nature is also a scene of a prehistory which is wiped away – a murder that has left no traces. In this state, the basis of our social relations is conflict. What more, the social contract encompassing the sexual contract excludes women, as Carol Pateman (1988) has identified. Women are absent, they’re somewhere in the scene, but not a figure and not represented. The scene we are represented with has no consideration for (inter)dependency. As such Butler argues that we need rethink our existence within a different imaginary. To this end, she offers a more promising and honest account of the interdependent nature of humans.

“Let’s start with a different story.”

And this is her story: no one is born an individual, no one can escape radical dependency. No one stands on their own. We all find ourselves dependent upon infrastructures as well as environmental support. Before turning to interdependency, Butler, however, mentions dependency and the problems it causes, and how there is no overcoming of dependency of childhood. ‘We become creatures who imagine ourselves self-sufficiently, yet are constantly realising this is not the case’. The mirror-stage in Lacan is one Butler with sarcasm and deep seriousness reads as a homosexual scene – it is here man sees himself in the mirror for the first time and falls in love. Literal individualism shares this scene of non-support with the mother’s support – she must be holding the boy before the mirror. The a-symbolic structure we are presented with do not offer us an alternative, so is there another way out?

Interdependency (as opposed to dependency)

The avowal of a politics of interdependency is necessary to imagine global obligations. But where do we find such obligations in the relation between subjects? To this end, Butler argues that equality presupposes a subject, but not based upon the relational aspect between subjects so that equality emerges as a feature of social relations rather than of subjects. Thus, obligations follows from interdependency insofar as they are needed for any structure. Such obligations, she claims, must be of post-national character and can, therefore, only mean that no borders exists. What is entailed, is not a call to overcome dependency, but to accept interdependency as the relation of equality – a relational equality.

The critique of dependency is illustrated in political economy as well as in relation to the normalisation of colonialism. It is good to overcome dependency, because it often means an end to colonial power and thus emancipation. But is this an emancipation of individuals or is it the emancipation? Independence can lose sight of interdependency, when sovereignty means the sovereignty of the individual. Consequently, worldly cohabitation becomes difficult to imagine. We cannot be partially individuated and be interdependent – that just sustains conflict, Butler claims.

Surely, Butler is not arguing to continue any form of colonial power, but she does remind us of an important lesson in decolonisation processes – that sovereign individualism comes with a price. It is not the only available alternative to the colonial present, and thus she returns to interdependency and violence, and the destructive power of relationality.

Interdependency and Violence

If we are stuck in individualistic fantasies, interdependency is written over. Such a violence is committed to inequality. How is the human produced?, Butler asks. Who counts? Whose life is grievable? The human cannot be the ground of our analysis, as the human is contextually variable and produced through violence. The human is haunted by exclusions. Such an unequal distribution of grievability is operative in life – it marks the value of creatures and decides if they can be treated equally. Thus, equal grievability is linked to interdependency, it is a relational character of equality, which minimises harm and destruction.

A politics of non-violence, then, offers itself as up to the task of opposing the bio-political. The “tacit war logic” of the bio-political, sustains and justifies the very destruction of other populations. As Butler writes elsewhere, and reworks her own conception of the bio-political writ large:

How that interdependency is avowed (or disavowed) and instituted (or not) has concrete implications for who survives, who thrives, who barely makes it, and who is eliminated or left to die. I want to insist on this interdependency precisely because when nations such as the US or Israel argue that their survival is served by war, a systematic error is committed. This is because war seeks to deny the ongoing and irrefutable ways in which we are all subject to one another, vulnerable to destruction by the other, and in need of protection through multilateral and global agreements based on the recognition of a shared preciousness (Butler, 2016).

Distinguishing violence from non-violence is difficult in a world of strategic war. Given the sociological “fact” that the state has monopolised the use of ‘legitimate’ violence (Asad, 2007), should we or should we not commit violence? Semantically we have stabilised both terms (violence and non-violence) in such a rendering, and yet we need to understand how power through violence is framed. Can we map it on a political frame so we can make sense of our public sense of practice? Anddevelop a meaning of what violence is, in order to seek a new biopolitical abandonment of violence – to break open the horizon and fight those committed to destruction – to perform the counter-strike to the strike? We need a new perception, a new imaginary, which has no sorrow, where lives are sustainable, liveable, and equally grievable. Non-violence is not the will towards peace, but rather a politics of non-violence is equally one of aggression: ‘But aggression can and must be separated from violence (violence being one form that aggression assumes), and there are ways of giving form to aggression that work in the service of democratic life, including “antagonism”, and discursive conflict, strikes, civil disobedience, and even revolution’ (Butler, 2016). Relations between people are persistent and interdependent. We might live in the impossible world, the opened struggle – but we cannot fail to subdue destruction.

By way of conclusion, Butler’s talk with its focus on interdependency, and her radical critique of the subject of liberalism, as the self-possessive upright man, stands as a revolutionary posture towards the sources of global suffering in the present conjuncture. Anti-capitalist, feminist, anti-imperialist, and radically democratic, Butler’s latest work has forced us, in a time of increasing nationalism, patriotic populism and the individuated-ness of precarity under neo-liberalism, to recognise the urgency to act globally, and to think of new forms of political obligation, not to the state, but to the world, and the global responsibilities that entails. This requires a radical rethink of our current and prevailing conceptions of responsibility, which need not be individualised and must not drift towards new forms of imperialism. But rather recognise and think anew the facticity of our radical interdependency and ontological vulnerability to one another. As Butler asks herself: ‘Can this insight lead to a normative reorientation for politics? Can this situation of mourning – one that is so dramatic for those in social movements who have undergone innumerable losses – supply a perspective by which to begin to apprehend the contemporary global situation.’

Hasret Cetinkaya is a doctoral candidate at the Irish Centre for Human Rights at the National University of Ireland – Galway. Her research interests are postcolonial and feminist theory, gender, kinship and the sociology of human rights.