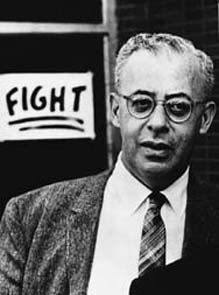

Recently put under the spotlight in France by Melenchon supporters, Saul Alinsky’s “community organizing” intends to politicize the everyday life of working classes by organizing concrete actions hand in hand with inhabitants. Randy Nemoz sees it as one of the springs of a populist strategy able to oppose a united people against the oligarchy.

Naming the adversary, creating a collective entity: the frontier “we” / “them”

Populism, seen as a way of doing politics and not as an ideology, draws a line between two strata of society whose deeply asymmetrical relationship creates on one side the people, to whom populists claim to belong, and the adversary: the caste, the oligarchy. A frontier between “us” and “them”. They are the powerful, those who rule and dominate in their own interests. And the plural takes on its meaning: it is not a single class nor classes with totally unified interests. However, they recognize their common adversary — us — and accept their interdependence as much as the organized competition that drives them to jostle each other, in a game with rules fixed by themselves, around their compromises.

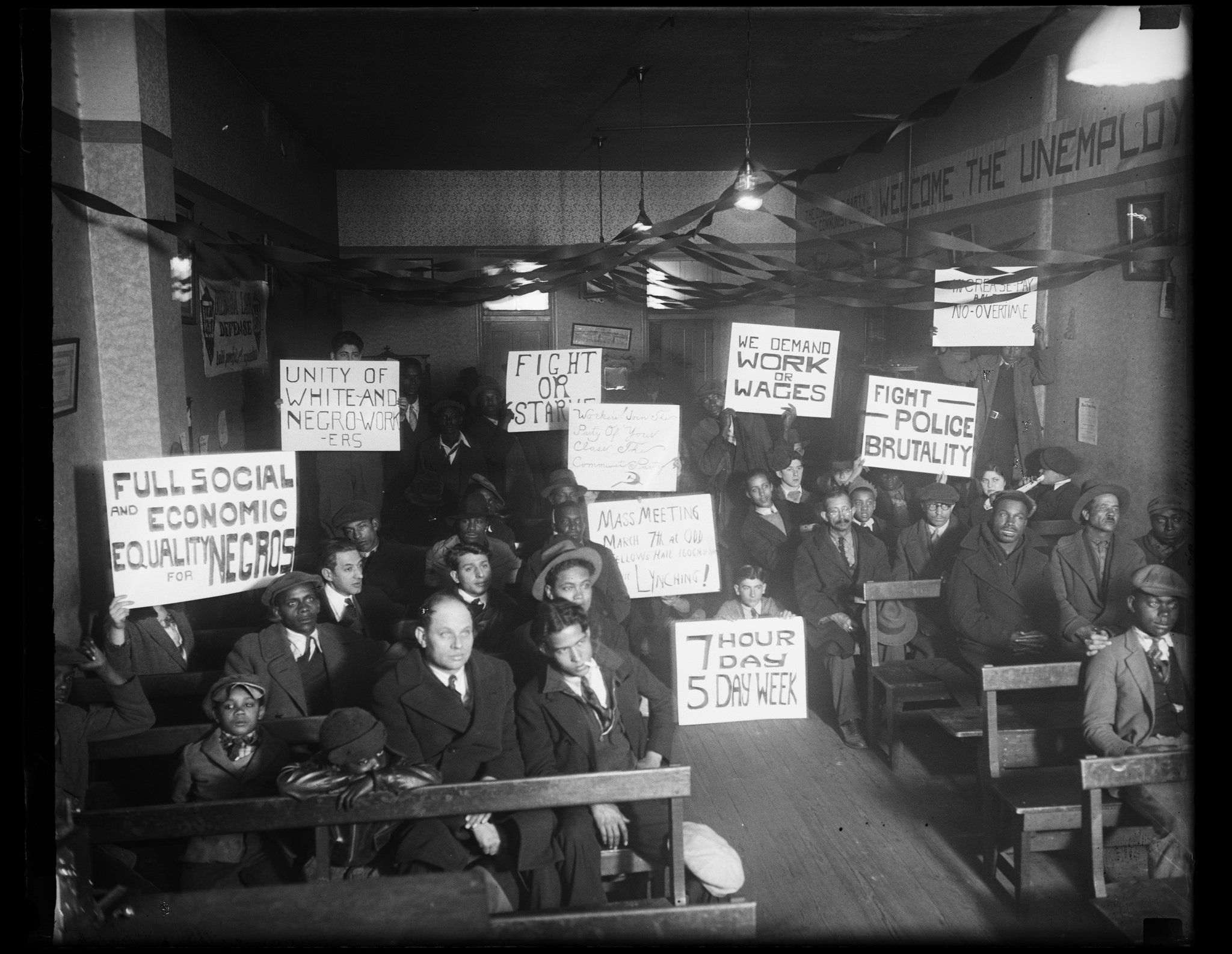

This relationship, between them and us, is unbalanced: this is the statement made by Alinsky when he studied the causes of crime in the American suburbs of the 1930s. His main concern was to overcome the divisions and fatalism of the most disadvantaged classes, especially those living in the most precarious neighbourhoods, so as to readjust the balance of power which opposed them to an oligarchy based on very well structured authorities, policies and employers’ organizations. For Alinsky, community organising facilitates a change in the balance of power in favour of isolated citizens against their powerful rulers. It fosters the constitution of a welded group, composed of previously isolated individuals, now much more capable of fighting than if they had remained mere scattered units.

Community organizing can become the weapon of the oppressed in plebeian suburbs. Build relationships, target a powerful person, prove his responsibility and act as a group to win concrete gains. Celebrate victory, and, finally, recreate a collective. The most important thing is to break with the atomization of individuals.

The first parallel we draw between the populist strategy and the Alinsky method appears to be this “targeting the powerful” mechanism, which determines a frontier and creates an “us” in relation to this “them”. Some will speak of constitutive exteriors —the “us” only exists through the existence, and the recognition of a “them”, an external element. The American criminologist recreated a sense of community from scratch, notwithstanding the diverse interest of the isolated individuals that composed it. In the populist strategy, this constructed community is the people. Facing this newborn entity is the cause of common evils: namely, the holder of political power, the administrator, or the boss. In so doing, the Alinsky method approximates what populists call the oligarchy, or the caste. In both cases, a border is drawn between a “we”, a local community or people, and a “them”, whose individual names are numerous —but identified— and whose dominant position is proven.

Weaving anger, an equivalence chain?

As already mentioned, whether the strategy is concerned with the people or the community, it always amount to a political creation. According to Alinsky, the task of the “organizer” is to “weave the anger” of the locals. This means starting from what their concrete experience, before explaining them that they are not isolated, that others share the same negative experience, and that behind these problems the same cause or person often hide.

Populists use a similar strategy and think of it in terms that can be easily paralleled. Ernesto Laclau, promoter of this strategy for the socialist camp, called for the constitution of a chain of equivalence between the various ‘democratic demands’ of society. From this chain between different groups can emerge a dynamic people, united around new common symbols —”empty signifiers’— invested by populist strategists to bring diverse groups together. In other words, the task of the “political organizers” consists not only in gathering neighbourhoods, but also in weaving collectives, associations, or individuals with different democratic claims —that is to say different groups of oppressed people requesting accession to various rights. For today, the strategy would be to articulate demands as heterogeneous as that of the ecologists, the feminists, the trade-unions, the LGBTI activists, the democrats, the humanists, the animal right advocates, the unemployed, the students, and so on. By weaving anger we can make sure that isolated groups and individuals understand the similarity of their claims and unite to tip the balance of power in their favour.

Avoiding populist identity drift: ensuring upward verticalization of anger

When one adopts the Alinsky method, however, one immediately confronts issues raised by the “horizontalization of anger”. For example, it is common to hear that the problem is the immigrant who squats the neighborhood or steals the jobs of young people, or that the problem of youngsters is that they prefer to sell drugs rather than go to work. “Horizontal anger”, in other words, arises when angry communities targets other individuals or groups who shares their situation of oppression. The challenge of the organizer will be to redirect anger by showing that those who are really responsible for the situation are those who really have power. In the populist jargon, this is called “verticalizing” horizontal anger. An upward verticalization, because it is not about having a horizontal anger, often fanned by the right-wing populists —it’s my neighbour’s fault because he does not have the same culture as me though he works in the same factory as me— nor a downward vertical anger, by which oppressed people target people even poorer than them.

The populist drift precisely consists in this horizontalization of anger, scapegoating altogether the oligarchy and the so-called the parasitic classes supposedly allied to it —the immigrants, the slackers, and so on. Such a turn leads to the creation of an identity-based people, grounded on common cultural characteristics, which excludes all those who do not share them. Against this drift towards identity populism —or right-wing populism— we shall oppose a democratic, social populism —or ‘left populism’ in the words of the thinker Chantal Mouffe. The purpose of left populism lies in organising the upward verticalization of anger, as in the Alinsky method: it is not based on the ethnic people, but on the class-people, the one who combines the plebs, dominated classes, employees, workers, peasants, small employers, civil servants, lower executives, teachers, craftsmen, students, unemployed people, etc. This progressive people does not pay heed to vain cultural, ethnic or religious quarrels, but targets the dominant groups of people and organisations who have led and still run the world and are accountable for its current state.

This article was first published in Le Vent Se Leve on 28 January 2018.